Human beings are social animals. In our everyday life, at work, with our friends and relatives, we are confronted with situations that require constant interaction withothers. While suchcircumstances often (ideally, always) bring somesort of benefit toall parties involved, there is a potential for conflict. In this issue, we look at the different types of conflict and how to respond to each one (“best practices”)—the ultimate goal being able to avoid conflict altogether.—MicheleTesoro-Tess, TWA Soft Skills Editor

Social institutions such as families, organizations, companies, and religious institutions provide us with moral principles and guidelines to deal with interpersonal conflicts that may occur within these institutions and in everyday life. However, notwithstanding this role taken by social institutions, interpersonal conflicts are numerous and arise daily and can be traced back to three main types of conflicts:

- Conflicts of power.

- Conflicts of interest.

- Conflicts of ethics (moral principles).

Conflicts of power. The issue at hand (very broadly speaking) is the power to have someone carry out or refrain from performing a specific action. In companies, this type of conflict is normally managed through hierarchy. A hierarchy-based organization manages power with the “top-down” approach. In theory, if the logic of this structure were strictly adhered to, no negotiation would be required or necessary, and one could assume that conflicts of power never exist between the managerial staff and the employees they are supervising. However, as we all know, conflicts of power do occur at the workplace, and it is most likely that we all have been involved in or have witnessed one.

In companies, however, it is much more common for people to be faced with conflicts of interest, which are usually the result of a failed hierarchy principle. The most classic example of a conflict of interest is a situation in which two people have a different perception of their “applied effort” in doing something and the “expected return” or reward that is granted to them. In this case, the company’s structure does not always provide such straightforward solutions.

On the other hand, a clear definition of roles and responsibilities can reduce the experience of disenfranchisement and antagonism among coworkers. An alternative solution is the development of the awareness of the individual and mutual trust. It is not by chance that in modern companies with a “flat” organizational structure there has been an increased emphasis on team building and on the promotion of team spirit.

Values, “ways of living,” and traditions can also be grounds for contrast: the conflicts of ethics. Time and again, companies are faced with decisions that are not exclusively technical or operational. To avoid the risk of decision paralysis, companies provide their professionals with a predefined values system. “Mission, Vision, and Guiding Principles” manuals are, in fact, a coherent system of values that can serve as a model of reference, providing employees with a general path to follow when making daily decisions. Companies are increasingly becoming more “horizontal,” as we witness the dissemination of value charts and guiding principles that serve to ease the animosity that can take place in an organization, where the power of superiors is progressively decreasing.

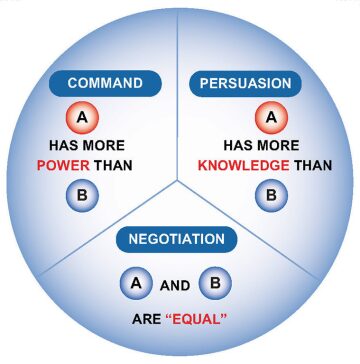

If we accept the idea that conflict originates from resisting the influence that someone tries to exert, psychologists have identified three types of influence (Fig. 1):

- Command, which emphasizes power.

- Persuasion, when the two parties confront each other, sometimes stressing principles and ethics.

- Negotiation, when the parties in conflict reach an agreement, exchanging ethical values in the process.

Command occurs when Person A has more power (physical, social, etc.) than Person B, allowing A to obtain what he/she wants from B. Still, in a situation such as this one, it is more important that B recognizes and accepts the power exerted by A.

The use of power as an influencing technique is typical of the animal kingdom, in which the parties involved do not have the intellectual capabilities to engage in more-refined modes of negotiation. However, commanding is also used by people under specific circumstances (e.g., in highly hierarchical organizations).

Persuasion takes place when A has more knowledge and/or information than B. Equally relevant to this concept is that B recognizes the fact that A is in possession of more knowledge and information, and accepts being persuaded by A. Examples of influence exerted through persuasion are ever-present in our daily lives: we grant credibility to doctors, lawyers, teachers, and bankers and accept their advice.

In negotiation, A and B regard themselves as equals and capable of reciprocally influencing each other. The first step in negotiating is for the parties involved to recognize each other. An example of the opposite is typical of kidnapping situations: in most countries, governments and police forces refuse to deal with kidnappers at any level because dealing with them would be seen as legitimizing their cause. In general, it is fundamental to be cognizant of the fact that the principle of reciprocity is one of the distinctive elements of negotiation.

Negotiations often present themselves as situations that are in “volatile equilibrium”: each time one of the two parties perceives itself as having obtained more power, command will be used, while every time one of the two parties perceives itself as having obtained more power, command will be used, while every time one of the two thinks itself to have gained more credibility, the persuasion technique will be resorted to. Trying to persuade instead of negotiating is one of the most common mistakes poor negotiators make. It is important to bear in mind that in successful negotiations, the two parties never want or try to change each other’s opinions and set of values.

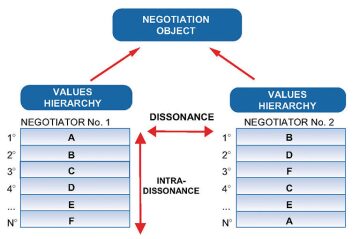

In fact, it is quite possible that negotiations take place between people that believe in different values. The conflict between different sets of values is an instance of “dissonance.” Dissonance is generated when a situation brings about contrasting ideas (e.g., the action of smoking evokes the ideas of pleasure on the one hand and of bad health on the other). These concepts (“pleasure” and “bad health”), although linked through the act of smoking, are contrasting in nature (i.e., they are in dissonance). The stronger the contrast, the more dissonance there is (Fig. 2).

Leon Festinger, the late social psychologist, best known for his work in cognitive dissonance, believed that individuals, in the long run, cannot tolerate high levels of dissonance. To overcome the problem, therefore, one should place one of the two values above the other; this psychological approach is called the reduction of dissonance.

In a negotiating situation, to reduce dissonance means activating an “exchange process” between the values that are in play from the two parties. In other words, by offering to give up less important values in favor of others that are more important for the other party, one is actually attempting to ease the dissonance. To cite another example of negotiating tactics, former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger produced a few practical tips that he used more than once in his negotiating experiences, a couple of which are pertinent to the theme of negotiation skills:

- The first tip is to “start cleaning artichokes from the external leaves,” which means that one must never start the negotiation process addressing issues that are more important to him/her, but should concentrate on issues that are more important to the other party.

- The second tip is to limit a proposal to one or a few variables/points. In the peace treaties between Israel and Egypt, for example, Kissinger used the step-by-step technique. Through this, he approached the U.S. and Egypt on many occasions in order to address and iron out several details of the agreement.

Focusing on the details, from the most crucial to the most minute, is fundamental to a successful negotiation and to mitigate the risk of conflict. It is also of vital importance to take the psychological and methodological aspects of the people you are negotiating with into consideration. Through this, we can fully understand who we are negotiating with, the underpinning values, and the objectives and the means by which these could be achieved, without making the mistake of getting sidetracked or steering the negotiation in an unfavorable direction. Also, it is crucial not to regard a negotiation as a conflict that generates a winner and a loser, but simply as an opportunity to exchange and develop ideas and viewpoints, with the ultimate goal of reaching a reasonable conclusion.