I would like to think that we all have choices about how to handle difficult people at work. Though sometimes we find that our old patterns of behavior in dealing with hard-to-manage people may limit our thinking and thus, our effectiveness. It is essential to revisit all of our choices before we are in a crisis or a time-bounded reactive situation. When working with hard-to-manage people, the real challenge is to step back, listen carefully, and figure out what our choices actually are. And, as we know, yet often forget, the process of creating practical choices must begin from the employee’s perspective.

The Foundation: Self-Knowledge and Perspective-Taking

Know thyself. In order to truly understand the employee’s perspective, it is necessary to understand your own motives, your own preferences, and your own biases. Know thyself and, in doing so, develop the capacity to know others. Dealing with difficult people takes a kind of personal confidence and strength—an awareness of yourself, a degree of emotional intelligence, and a sense of self-control. Bossidy and Charan, in their book, Execution, remind us that “emotional fortitude comes from self-discovery and self-mastery.”

The other’s perspective. Most models of management, leadership, and coaching include the requisite skill of assessing the needs and wants of the people in your organization—for example, your employees, boss, peers, and clients. Experts agree that when we focus on building and maintaining healthy, trusting relationships in the workplace, we positively impact morale and productivity. Likewise, we are continually reminded that the core of effective communication begins when we decenter and examine situations through the “other’s” lens. The cliché of “perspective is everything” has new meaning, when applied to working with difficult people. Understanding and adapting to their perspectives are essential.

The combination of self-knowledge and perspective-taking establishes a foundational framework for dealing with difficult people. With this framework, you open to practical choices for handling difficult people. The process can be broken down into three steps.

- Start by examining your comfort zone, your natural response zone. How do you typically react to hard-to-manage employees?

- Analyze the employee’s needs and wants. Look at the situation from the employee’s point of view. Defuse the emotions that interfere with decision making and productive action.

- Reassess the situation and see how to formulate decisions from a position of balanced perspective-taking while still respecting the needs and wants of the employee.

It is important to note that while the steps are simple to understand, breaking old and ineffective reactive patterns is very difficult for most people.

Two Approaches: Reactive and Responsive

Working with difficult people requires skills both in management (within the system) and coaching (at a personal level). These go hand-in-hand. Management implies making decisions about efficient planning, implementation, execution, and outcomes. Coaching implies setting personal direction, understanding individual context, generating solutions, motivating, offering support, and inspiring outcomes.

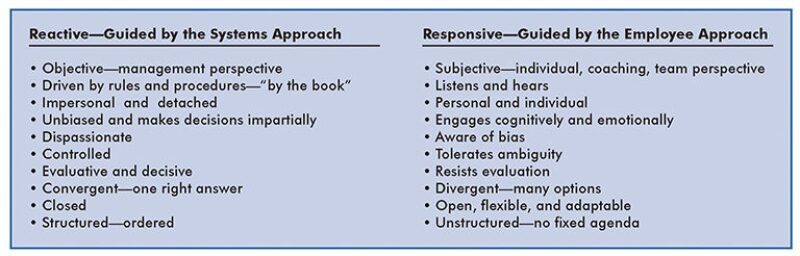

These roles are similar but they are distinguished by the subtle nuance of perspective—the reactive-systems approach and the responsive-employee approach. The reactive-systems approach is guided by the established system of the organization, the system into which the employee must “fit” (a more impartial approach, during which we react by staying within the established system). The responsive-employee approach is guided by the needs, wants, and feelings of the employee (a more individualized and responsive approach).

Both these approaches may be useful in making decisions about how to deal with difficult people. Consider your “most difficult” person at work. When you interact with this person, are you guided by a systems approach, the employee approach, or both? The descriptors in Fig. 1 can help you determine this. Which one best fits your own natural pattern? With which do you most identify? Where are you most comfortable? Do you see yourself on both sides? Does it depend on the individual? Does it depend on the situation? Different people will answer differently.

Long-time coach of the Dallas Cowboys football team, the late Tom Landry, said that leaders get “someone to do what they don't want to do, to achieve what they want to achieve.” From this two-sided vantage point, hard-to-manage employees may not be able to see the company’s perspective and, thus, may not know what they need to achieve if they are going to excel within the company’s system. However, when a manager reacts too impersonally, by telling an unhappy employee what the company needs the employee to do—even when the manager knows it is best for him—the result often may be an irrational employee reaction (anger or withdrawal). Instead, a manager might handle the employee with a personal approach—listen, engage without judgment, and field the employee’s responses with empathy and sincerity. In this way, you may be able to understand a bit more about the context and underlying reasons for disagreeable employees’ behaviors. Through understanding others’ perspectives, you may be able to help them buy into the company’s goals. Employees need to buy into an idea from their own perspective to achieve what they want to achieve.

Balanced approaches start when we become aware of how we interact with and respond to that difficult employee—in a reactive way or responsive way, or a little of both. Because none of us really fits into a box, it is more realistic to talk about degrees—how much of an objective, reactive-systems approach and how much of a subjective, responsive-employee approach is needed with a particular person in a particular situation. Our goal is to maximize the human capital of our employees, and this is usually a balancing act, in which we keep employee morale and satisfaction high while keeping the structure, productivity, and company profit margin in sight. Therein lie the choices we can make when handling difficult people.

Step 1: Determine Your Natural Comfort Zone

Start by examining your comfort zone, your natural response zone. How do you typically interact with hard-to-manage employees? For instance, many technical companies face over-the-wall engineering issues. Consider what you might do when Tony comes into work in a seemingly bad humor and says:

“I can’t believe the design department handed me this ridiculous project. How’s my engineering team supposed to build this without decent specifications? They do this all the time. Do they think we’re mind readers or magicians? I’m going to send production an email and let them know we’ll never make the deadline on this one. The customer will just have to wait.”

In which way are you more likely to reply?

A. Reactive Manager—Guided by Systems Approach

“Well, this sometimes happens but you’ll just have to make the best of it. I think the design department has given you enough to go on for now. Look at it this way; it’s better to tackle the problem than to complain about it. The deadline holds. Let me know how I can help and where you are on this project next week.”

Your reasoning as the reactive manager. Rules are rules, and the company has a framework for how to do things: design®build and test®produce and commercialize. Your job description is to find the solution, solve the problems, and build the prototype. As your manager, I am decisive, in control, and willing to support you. But the company’s deadline is very important. We’ve been in situations like this before. Stop complaining.

B. Responsive Manager—Guided by Employee Approach

“Wow, let me look at that project. It sounds like you’re frustrated with the design department and worried that you won’t be able to give your engineers enough details to work efficiently on this project. Sit down, and tell me what this is all about.”

Or…

“I don’t blame you for being upset. Tell me a little about this project. What’s the history on this one? Given this situation, I hear you saying you’re a little apprehensive about making the deadline.”

Your reasoning as a responsive manager. I am empathetically listening. I hear you, and I have paraphrased what I think you might be feeling. I am not judging your anger, frustration, or apprehension. I am open to more dialogue about this situation.

These replies describe the extremes of how you might deal with a disgruntled employee. But it is important to be aware of your comfort level with each of these descriptions.

Step 2. Analyze From the Employee’s Point of View

How do you move between the extremes? Look carefully at the employee’s point of view. How do you do this?

- Respond, instead of react.

- Field the employee’s emotions.

- Open a dialogue with the employee.

It is important to keep in mind that difficult people at work don’t always mean to be difficult. They appear to be unhappy, agitated, discontent, or apathetic. In fact, from their perspective, it is often others whom they regard as difficult, uncooperative, inefficient, or unskilled. They rarely see themselves as the focus of problems at work.

Feelings drive behavior. Poor or unacceptable behaviors at work always come with an underlying set of feelings. For instance, when someone lashes out at a coworker, it could be because of any number of emotions—powerlessness, frustration, shock, rejection, outrage, intimidation, confusion, indignation, jealousy, fear, or exhaustion, and each of these feelings drives an exponential number of behaviors. We might as well say that no workplace behavior is devoid of an associated feeling.

Behaviors, by definition, are what we see and hear. They are observable actions, such as cutting sarcasm, uncooperative actions, rebellion, intraoffice destructive gossip, or just an obvious bad attitude.

Feelings often remain elusive. We only can see an emotion when it shows as a behavior. We only can hear emotions when we create a dialogue that invites emotions to be revealed. But, until we invest in uncovering the underlying feelings, the unchecked behavior will likely exacerbate matters, or worse yet, go underground. We can uncover the underlying feelings in simple and respectful ways (e.g., active listening).

First—a dialogue. The first step is to enter into a dialogue, defined as a conversation with the intent to really listen. The late quantum physicist David Bohm believed the purpose of dialogue was to drive conversation deep enough to understand underlying assumptions and beliefs. We can do this only by really listening, without initial judgment, until the emotion is emptied out and the “truth” becomes evident (the speaker’s “truth,” not necessarily your “truth” or anyone else’s “truth”). Dialogue is the basis for building trust. Hard-to-manage employees are less difficult when they trust you, or at least when they believe you are sincerely concerned about them and their “truth,” even though you may not agree with them.

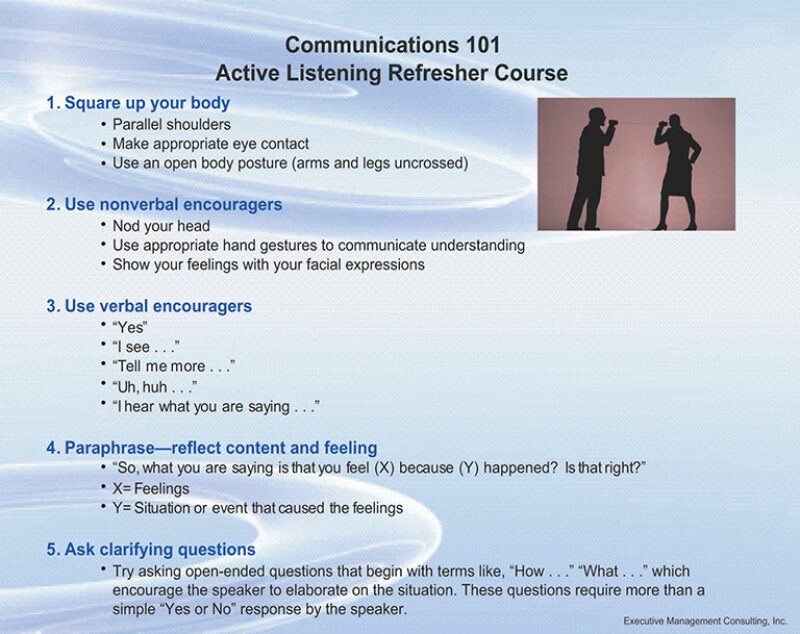

Really listen. Being attentive is very important, as professionals who work in human communication so often emphasize. Attention behaviors include such things as eye contact, leaning in, and nodding. But all of these work only if the intent behind them is real. If your nod is not sincere, your listener will know. Most people sense when they truly are being listened to and when they are not. True empathetic listening takes just that, true empathy.

Step 3: Reassess to Find a Balance

When feelings have been revealed, acknowledged, and validated through dialogue, and when the disgruntled colleague has “finished,” then the real work of balancing personal needs and wants against what is best for the company begins. When do you know that the speaker is finished and ready to hear you? Physically, you may notice more relaxed body language, perhaps the all-telling deep breath or sigh, or a change in posture (e.g., the shoulders relaxing). Remember, listen and field emotions first, then solve the problem.

A list of guidelines is provided in Fig. 2 that can accelerate the process of dialogue, conversation, and defusing of emotions, bringing you closer to finding the right balance of reactive-systems and responsive-employee approaches.

Tips To Remember for Being Responsive

- Listening takes time. It’s not a 30-second interchange in the hallway.

- Hearing disgruntled employees and fielding their emotions takes energy and sometimes lots of it.

- Empathetic listening means incorporating the employee’s message. You would like the employee to conclude, “Hey, this guy gets me.”

- While feelings are taking precedence, rational thinking and problem solving are not likely to be productive. There is a two-step process: listen, and then solve the problem.

- Do not evaluate the speaker’s feelings or behaviors as they are being conveyed. It is likely to “push another button” or end the conversation, with the employee concluding, “She’s not listening to me anyway.”

- Save evaluative comments for the end of the dialogue, after all the emotion has been poured off.

- Rational thinking and problem solving come at the very end of the conversation, when the speaker has cleared the emotions from interfering with logical thought processes.

- You are not a professional counselor; you cannot, and should not try to “fix” the employee. Human resources can make professional referrals when they are needed.

- Just be quiet, listen, and encourage. Most of the time, it is enough.

Achieving Balance and Strengthening Relationships

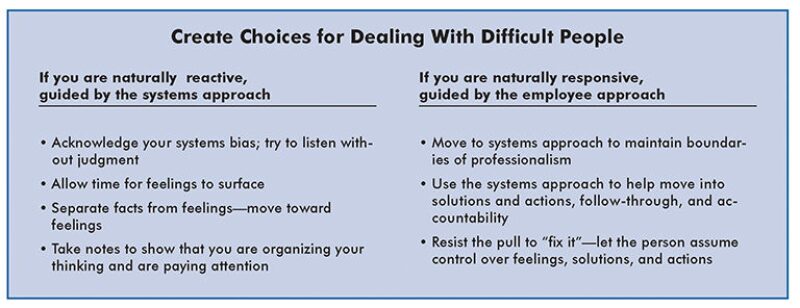

Depending on your natural proclivity, you may achieve a balanced perspective by means of different considerations. In Fig. 3 are some ways for managers with both preferences to move toward more balanced approaches. Consider the descriptions of the choices that you can make consciously when dealing with difficult people.

The overarching goal of working with difficult people is to build and strengthen relationships. In most situations, we work better (achieve higher quality), harder (are more motivated), and longer (work extra hours and show extra energy) with managers and fellow team members when we know a little about them and have developed a relationship. This is not to imply that we are in a popularity contest in the workplace, but rather to recognize that our work environment simply is more productive when the relationships between people are honest and meaningful at whatever level.

This article deals primarily with the power of being a listener and the need to foster a balanced perspective between reacting and responding when dealing with hard-to-manage employees. Two foundational communications techniques are discussed: the reactive-systems approach and the responsive-employee approach. Brief examples are given that help us imagine real situations and prompt us to think of what we would do in those cases.

Lisa Song, Karam Sami Al-Yateem, and Husameddin S. Al-Madani, Editors, Soft Skills