I remember my first year in the industry very fondly: it was 2006, oil prices had been climbing steadily for over half a decade, and the “big crew change” was starting to become dinner table discussion. The brain drain that would eventually come from the retirement of senior employees was imminent, experts advised, and it seemed like companies were taking advantage of the good times to hire like crazy as they positioned themselves to hedge the effect on their operations.

I vividly remember a recruitment event organized by a large independent during the ATCE for which they rented the entire Sea World theme park in San Antonio and threw a party for us. It was an extraordinarily memorable event for any impressionable recent grad, and the future seemed prosperous. The Petroleum Economist encapsulated the hiring spree by quoting the head of US recruiting for one of the supermajors as saying, “Times are very good for us…and we are expanding–USD 60 [a barrel] oil will do a lot for your business. At the same time…a large number of employees are in their 50s and we need to increase our hiring across the board.”

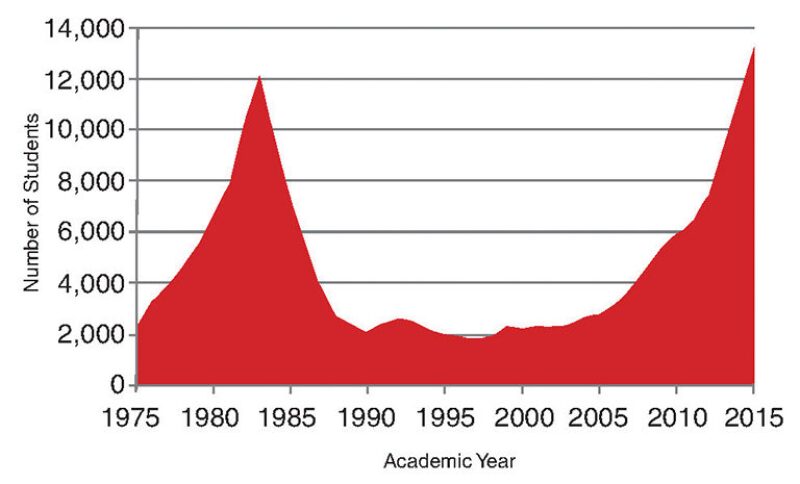

Academia listened to industry’s pleas for help, experiencing a meteoric rise in petroleum engineering enrollment not seen since the 1980s (Fig 1). Unfortunately, those students in the 1980s largely found themselves unemployed upon graduation as a result of cost-cutting measures following the oil price collapse of 1987, the result of which became the very same “lost generation” of talent that evidently now needs to be bridged by the big crew change.

Fast-forward to today and, after some wild swings in commodity prices, to be sure, we nonetheless see oil once again hovering at around the same USD 60 mark which I fondly recall from the birth of my career. But a quick study of the headlines paints a starkly different picture this time around, as seemingly every company is either laying off people, freezing hiring, or doing both. An onslaught of such headlines has turned the mood in university campuses to an anxious and somber (if not pessimistic) one, which is completely opposite to the confident euphoria when I was there. I encourage you to read the TWAInterAct section, which features comments from SPE student chapter presidents on how the price drop is affecting students.

According to a Schlumberger Business Consulting study reported in the Houston Chronicle, our industry was expected to have a net loss of professionals by 2014-2015 due to retirements, and that was before today’s commodity-driven hiring freezes and early retirement packages. This means that as the big crew change is finally under way—and the industry prepares to feel the effects of its neglect on its workforce during the 1980s and 1990s—academia is beginning to experience the same cold shoulder from the industry in the form of underfunding and low hiring that it felt back then.

It is a tough but understandable decision for executives: do you stay the course and allow your company to hemorrhage right into bankruptcy, or do you cut costs any way you can (even if it means laying off people) to try to secure the future of the business? Your employees (those still around, anyway) and shareholders would certainly support the latter.

Final Thoughts

At a time when the wound is still healing from the damage of the 1980s, we as an industry must ask ourselves whether ripping the scab off by virtue of another lost generation will in fact leave a permanent scar and cement our reputation as an industry of boom/bust hiring—incapable of protecting the lifeblood of the business by adequately managing knowledge transfer between generations. The irreparable effects such a reputation could have on the industry’s pipeline of talent are self-evident and too grave to want to think about. Students will always be pragmatic about their careers and, facing an uncertain future, they will seek alternatives and, more than likely, never return.

Indeed, the similarities between the 1980s and today are too many and ominous to ignore. Does the cyclical nature of our business automatically doom us to these lost generations during each abrupt dip in commodity prices? Or will there be a generation that finally says, “fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice…”?