Assuring that energy professionals have the specific competencies they will need to meet the needs of an evolving work environment is a critical challenge. What competencies will have the most impact on the oil and gas industry in the future, and are the current energy professionals ready for what they will face? What role can academia and SPE play in preparing young professionals (YPs) for future competency requirements? Find out the views of YPs on this stimulating subject.

Rita Onyige, Herve Gross, and Anton Andreev, Editors, Forum

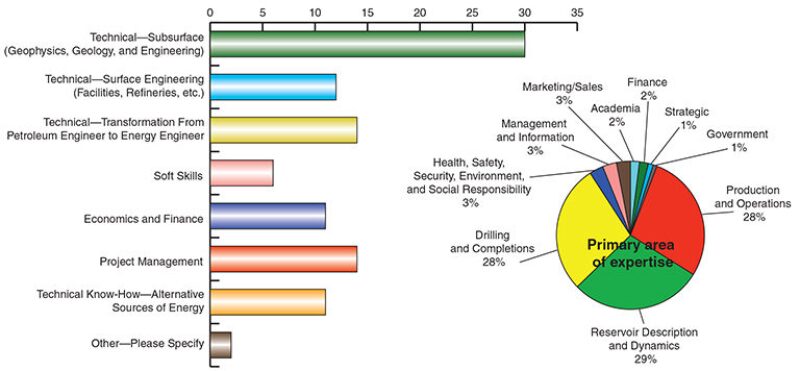

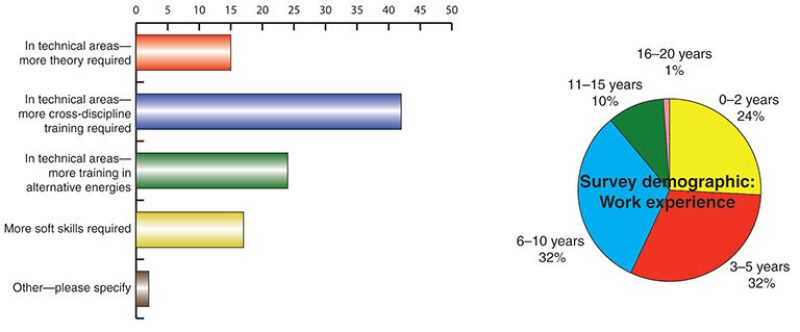

A total of 340 readers responded fully to the survey. By nationalities designated, the respondents were 38% North and South Americans, 27% Asians, 17% Europeans/Russians, 13% Africans, and 6% Oceanians. Half of the respondents listed a primary work location of America, Europe, or Russia. The male/female ratio was 80/20. About one-fourth of the respondents were fresh graduates with 0–2 years’ experience, while 65% had 3–10 years’ experience. Most of the respondents work in the domains of reservoir description and dynamics, production and operations, and drilling and completions, with the figures being approximately 30% for each.

This survey is a discussion on the views of the respondents on competence requirements for the energy industry in the future and plans to meet these requirements. Their current competence level on the job and expectations from SPE young professionals (YPs) were also reviewed.

Competency Requirements and Future Plans

What are the main competence areas that will make an impact in the oil and gas industry heading into the future?

Most respondents believe that technical competencies will have the most impact, and 42% of respondents emphasized the importance of technical knowledge of the surface and subsurface. The paradigm change from petroleum engineer to energy engineer—and its corollary relating to alternative energy—placed second, with 25% of respondents citing them as most important. Project management and other soft skills were identified by 20% of respondents as being most important.

The demographic data displayed (Fig. 1) indicated that 85% of respondents worked in technical areas, such as drilling (28%), reservoir description (29%), and production and operations (28%). These domains are part of the historical core of petroleum engineering. Notably, however, even the remaining 15% of respondents, who identified themselves as nontechnical specialists, considered the core technical competencies as most important.

The resources and technologies in the energy industry may change significantly over the first half of this century. Do you feel that your current experience and/or career path will provide you with adequate competencies to adjust to this change?

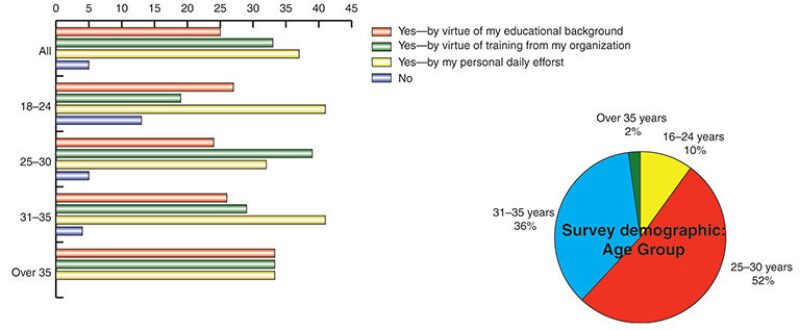

A third of respondents have personal plans in place to prepare themselves for coming changes, and 19% stated that they already have adequate training and experience to ensure proper adaptation to changing conditions. Approximately 12% of respondents believe that fossil fuels will remain the main source of energy for a long time because hydrocarbons will continue to be more economic than alternative resources. About 18% of respondents said they are not sufficiently prepared for possible changes in the industry.

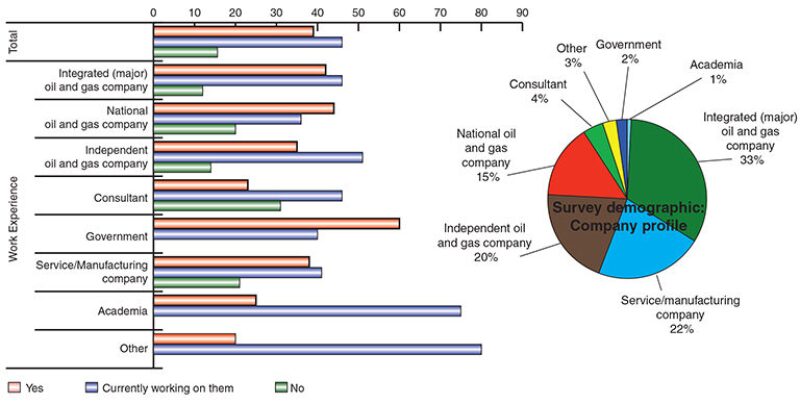

Experience on the job is an asset for adaptation to changing environments (Fig. 2). The percentage of respondents indicating adequate training and experience increases commensurate with length of service. Approximately 13% of them have 0–2 years’ experience, while 32% have 11–15 years’ experience. Several respondents expressed doubts about the scope of change and its impact.

To what extent do you have an understanding of the competencies required for your career progression in the energy industry?

A total of 68% of respondents indicated an understanding, “to some extent,” of the competencies required for career progression (Fig. 3). Notably, the willingness to claim “a great extent” of understanding on this issue increased with the level of the respondent’s experience. However, the fraction of respondents indicating that they were unclear about the required competencies of the future did not correlate very strongly with work experience. This suggests that career-development plans will remain unclear for a considerable time if not resolved substantially at an early stage. A small number of respondents said that they had no understanding of the competencies required for their career development.

Are there plans in place to ensure that you have the right competence to achieve your career growth within the organization?

Approximately 39% of respondents answered affirmatively, while 46% said that they are now working on their development plans, and 16% said they have no plans. The composition of the group indicating no plans included consultant-company staff as its largest component (31%), with its smallest component (12%) being personnel from major integrated oil companies (Fig. 4).

What additional areas might help fulfill the competence requirements for future careers in the energy industry?

For 42% of respondents, more cross-discipline training in technical areas is seen as the most critical need to meet future competency requirements, while training in alternative-energy sources was cited by 24%, and soft-skills development and greater emphasis on theoretical training in technical areas were cited by 17% and 15%, respectively (Fig. 5). Other areas, mentioned by small numbers of respondents, included wellsite experience, enhanced mentoring, leadership training, applied research, and technology integration.

What is your opinion of having a standard competency matrix on your job profile?

An overwhelming 90% of respondents endorsed having a standard competency matrix but emphasized that this is not enough. Job experience must also be part of the competency evaluation.

Current Job Competencies and How To Move Forward in the Future

Are you aware of the competencies required for your job description?

Answering affirmatively were 92% of respondents. The remainder, who answered negatively, consisted primarily of recent hires.

Are you adequately equipped for the competence required by your job?

Virtually all respondents (95%) said they were adequately equipped for their current job, with the primary impetus for that preparation coming from personal daily efforts, one’s current work organization, and academia, in that order (Fig. 6).

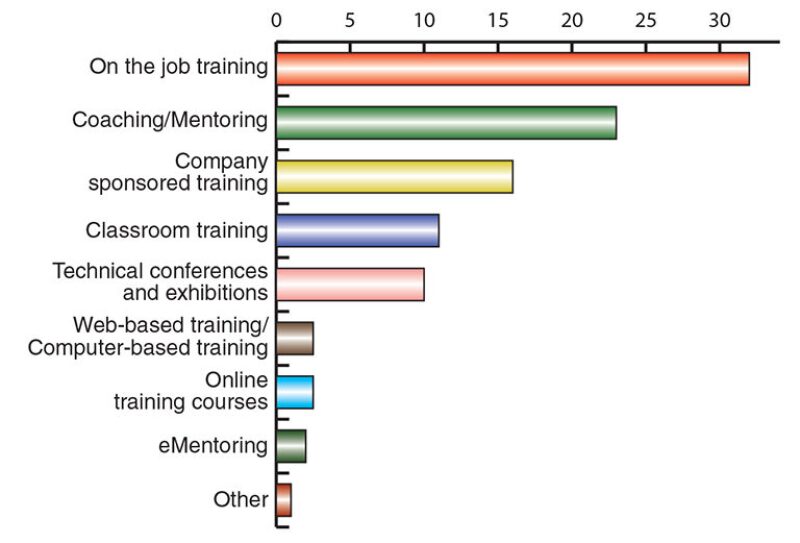

Which learning methods are most suitable for improving your competency?

One-third of respondents listed on-the-job training, while smaller but significant groups of respondents mentioned coaching and mentoring, company-sponsored training, classroom training, and technical conferences and exhibitions (Fig. 7). A handful of other training/learning venues were cited by a small number of respondents.

Could academia offer more training to enhance the energy professional’s competency for the future?

A total of 89% of respondents answered affirmatively.

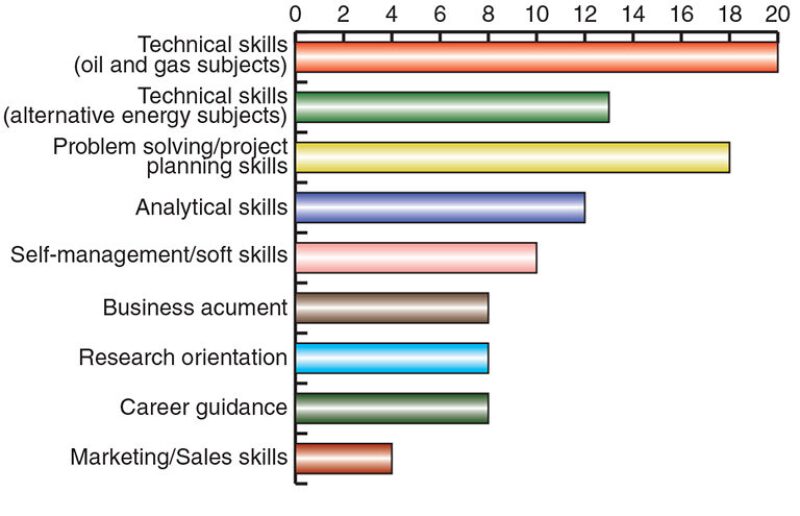

In which areas should academia offer more training?

Technical skills related to oil and gas received the largest response (20%), followed by problem solving/project planning skills (18%), technical skills related to alternative energy (13%), analytical skills (12%), and self-management/soft skills (10%). Business acumen, research orientation, career guidance, and marketing skills were also cited (Fig. 8).

Has your SPE YP group contributed to building your competency for your future in the energy industry?

A total of 41% of respondents said that they did not know if their SPE YP group had helped in this way, while 35% said their YP group had not helped. Of the 24% indicating that their YP group had helped build their personal competency, more than one-third were located in Asia and Africa. This suggests a need to energize and promote YP activities on a broad worldwide basis.

In which areas can your YP group improve?

Priority areas for YP group improvement, according to respondents, were networking with other YPs (24%), technical study groups (23%), and career guidance (21%). YP groups, thus, are perceived as a technical networking platform by 68% of respondents. Helping with soft skills and improving the global understanding of the oil industry, including its future, are also perceived as areas for improvement of YP group activities. Respondents additionally suggested that YP activities could serve as a platform for younger professionals to meet experienced employees, expanding networking opportunities beyond the circle of YPs.

Conclusion

In spite of evident changes in the energy industry, young oil and gas professionals do not express any concerns for their careers. According to them, fossil fuels are likely to dominate the future of the energy industry for the next decades. They are aware of possible changes in the set of competencies needed to adapt to the future, and they express confidence that their experience and formation will allow this adaptation. They have personal plans in place and benefit from the support of their organizations to fill the competency gap.

Most YPs see the need for more cross-discipline training and job-competence clarification as means of improving their competence at work. Academic training is considered important for acquiring core technical skills and needs to be complemented by job experience that can enable one to acquire other technical and nontechnical skills, such as project planning.

The SPE YP activities were not generally considered effective for building competencies. Those who expressed positive responses on this highlighted the positive role of YP groups during technical conferences and exhibitions. Respondents expressed a clear interest in having YP activities for technical networking and for interaction with experienced professionals, and respondents called for more visibility of local YP chapters.