Between training programs and moving to new locations, a lot can happen in the first 10 years of your career. The TWA Forum team informally talked with our colleagues and found that people whose backgrounds appeared disparate often voiced similar themes regarding what they learned in their first 10 years in the “real world” of the workplace. Below are the nine life lessons that emerged from these discussions—plus one for you to write.

1. What you do, or don’t do, creates the reputation you have amongst your peers. Be responsible for yourself—your conduct, your actions, and your behavior.

Your reputation in the oil and gas industry has been building since the day you entered the game and is being continually developed daily amongst your peers, co-workers, and other professionals. How you interact and deal with your coworkers, management, clients, suppliers, and contractors all play a direct role in developing and maintaining your reputation in the industry.

Your reputation is related to the value you bring to your company. And remember, first impressions definitely count, so always give a respectable handshake and smile. Timothy Price, president at Heath Energy Products Corp., says, “This is an industry where you will cross paths with thousands of people who all cross paths with each other. Therefore, nothing is more important than your reputation.”

When transitioning to a new role, realize that you should always “uphold your reputation, it will precede you and hold you accountable,” says Darren Vaught, special projects manager at Hydessco.

What underpins reputation is integrity. Larry Bartram, region account manager at Halliburton’s Multi-Chem, notes, “In any industry, honesty and integrity are first and foremost. Your reputation is of paramount importance to your success.”

2. Hold true to your integrity so that you can produce sound engineering work that aligns with your values. At its core, integrity means alignment between what you do and who you are. Being who you are can be defined by your personal values.

Professor Steve Begg, head of the Petroleum Engineering School, University of Adelaide, Australia, says to “never lose your integrity. The big ‘wrongs’ are obvious, though not necessarily easy to deal with. It’s the small things that can gradually lead you astray—no one instance itself seems that bad.”

Know that your decisions are impactful, and the results have some probability of spreading publicly across a wide swath of people. Chris Buckingham, program director at the Fluid Dynamics and Multiphase Flow Program at Southwest Research Institute, notes that “In all that you do, everywhere—not just at work—seek to have a reputation for impeccable integrity, only making decisions you wouldn’t mind being posted on a billboard at the side of the highway.”

3. Don’t let problems fester. Approach issues immediately, and talk with people to get your concerns voiced early on so that action can be taken. If necessary, changes can occur and if not, you can work on understanding the reasons why. Being able to go to sleep at night without worrying is a key indicator of how people deal with their problems.

Being able to—and actually—speaking up is critical to success, particularly in the context of safety. The oil field is one of the most dangerous places in which to work, but with the correct mindset and proper measures in place we can prevent accidents from occurring. Maintaining safety as an integral value will go a long way to having a long and successful career in the industry.

Imran Qaiser, directional driller and field engineer at Schlumberger, notes to “always take 5 minutes to analyze any task before proceeding. Communications is key. You have the authority to stop any job if you feel it [is] not safe.”

4. Know and plan to your rhythms to develop a sustainable routine. Plan accordingly, especially if you have weeklong training, vacation, or other events throughout the year. If you have the ability to control your schedule, try not to have a big meeting the day after a lengthy vacation. Try to arrange your vacation to occur after a major business planning cycle.

Though some schedules are unpredictable, elements of anticipation can still be engineered throughout the day. Even making small tweaks in when you perform detailed technical work and make decisions can have large gains in productivity. David Rock, director of the NeuroLeadership Institute, writes that “your ability to make great decisions is a limited resource…this means not thinking when you don’t have to, becoming disciplined about not paying to attention to nonurgent tasks unless, or until, it’s truly essential that you do.”

The cadence of the day can be arranged accordingly by focusing on the most important task each day. “For nearly a decade now, I’ve begun my workdays by focusing for 90 minutes, uninterrupted, on the task I decide the night before is the important one I’ll face the following day. After 90 minutes, I take a break,” says Tony Schwartz, chief executive officer of the Energy Project and author of Be Excellent at Anything.

5. Create a boundary between work and other facets of life to stay focused. Expect burnout if you cannot hold to these boundaries. It means not checking email when spending time with friends at a restaurant. It means not looking at Facebook while trying to read a technical paper. Freedom can be found in boundaries.

“Human beings are not designed to do activities simultaneously, but rather successively. In a world of relentless demands, it is only possible to main a high level of intensity if you create boundaries,” says Schwartz.

The key to creating the boundary is in understanding your own and your manager’s expectations, and ensuring that there is alignment between the two. According to an article in Fast Company, Ken and Scott Blanchard recommend that you and your manager each create separate lists of things you are held accountable for in your role. Afterwards, prioritize the list and ensure that you and your manager agree on the most important tasks. Having regular check-ins ensures that you and your manager stay aligned throughout the year.

Know that there will be times when work is a 24-hour-a-day marathon, such as during operations when your well is being drilled. However, there will also be times the focus will be planning the well or defining drilling rig specifications. Understanding the difference in response time between the two—operations and planning—is important in determining where boundaries can be defined.

6. Create and maintain your community. It is 2 a.m. A major problem is happening. You take the call and give a quick answer, but there are more engineering details involved. Know who you can turn to when you need help. Other people have faced many problems and have a lot of experience you can draw upon. You can find a solution simply by asking and listening to people in your network. Take notes when talking to these mentors—not just technical details, but also their personal lives so you can reconnect the relationship at a moment’s notice—even if you generally stay in touch in the first place.

In a Harvard Business Review article by Priscilla Claman, she recommends setting up a personal career “board of directors” you can consult and receive feedback from so you can grow. “The people on your board of directors should know more than you about something, be better than you at something, or be capable of offering different points of view,” writes Claman, president of Career Strategies Inc.

Often, one person alone cannot advise on both reservoir modeling and emulsion properties. Look inside and outside your company to develop those relationships—so that when you need it most, the experts are there for you. Often, these folks are found in previous roles, college, and online—on SPE Connect, LinkedIn, and other forums. The occasional email sent to the professors who helped you graduate goes a long way in maintaining those relationships. After moving on from one role to another, don’t neglect the previous relationships you made.

7. Never stop learning, and mature from your mistakes. There exists of a plethora of resources that can be very beneficial both technically and professionally in your career. Learning occurs in formal settings, such as training and in college, as well as on the job through executing your projects.

Regardless of the ways you’ve devised for retaining new knowledge, keep on learning something new, even from colleagues who sit next door. Thalbert “Thal” McGinness, a consulting petrophysicist, notes that you should “always be willing to listen first and learn something every day.”

Failure, though at times embarrassing and painful, is often where the best learning occurs. “Always remember, learning is a never-ending process. Listen to everyone, but apply your own mind. Take responsibility for your failures and more importantly—learn from failures. It is the failure which is our real teacher,” says Dr. Milap Goud, technical manager–Asia Pacific at Q-Max Solutions Inc.

The approach to learning is just as important as what is being committed to memory. Having an open mind enables the lesson to be learnt well the first time. “Always be anxious to learn because everyone around you knows more about something than you do,” says Heath Energy Products’ Timothy Price.

8. Field experience is critical. In the multidisciplinary oil field, gaining even a general understanding of field operations can save you and your company time and money. The knowledge gained by going to observe operations—or better yet, performing those operations—will help in asking the right questions about why cost and time were under-or over-projected.

According to David Dixon, a graduate production technologist (production engineer) at Shell, “[There is] no substitute for field experience. Theoretical understanding is great but you need to see it happen to understand the risks involved in any operation.”

Glenn Vawter, executive director at National Oil Shale Association and president of ATP Services, cuts to the core regarding the value gained from firsthand field experience: “If you don’t know what it takes to get it done in the field, you cannot design programs that can be carried out by those talented people who really get the work done, and done right, and done professionally.”

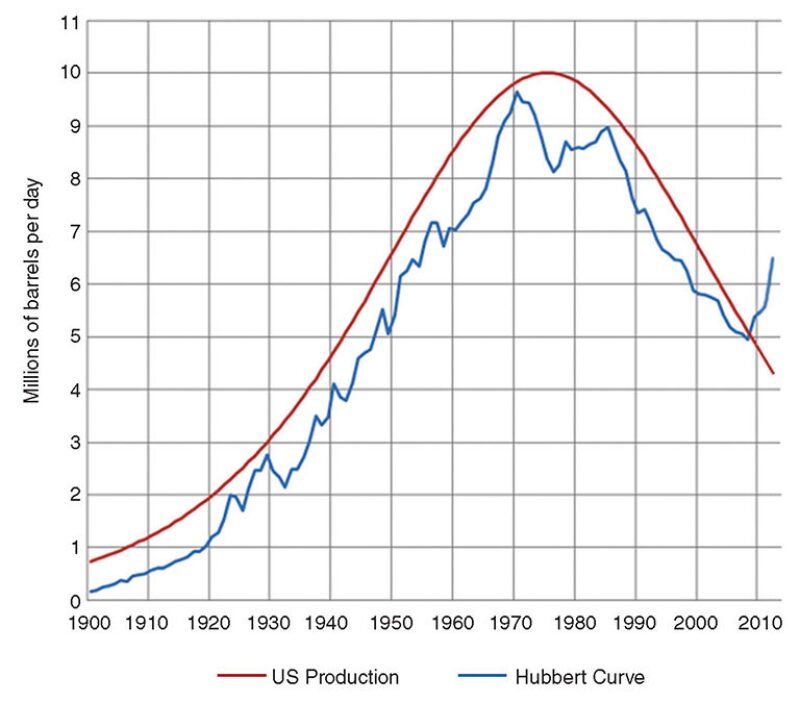

9. Be open to and accept change. In a publication titled “Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels,” M. King Hubbert predicted in 1956 that peak oil in the United States would occur between 1965 and 1971, However, he did not predict the rise in oil production from tight oil. Using a combination of hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling, the ability to produce from low-permeability source rock would not become economic until more than 40 years later. However, now those technologies have unlocked tight source rock and are driving current US oil and gas production. Dixon notes, “Always expect the unexpected. The oil and gas industry is terrible at predicting anything. Always have a back-up plan.”

10. Write your own life lesson learned in the oil field. Think about and reflect on the critical lessons you have learned. Pick the most important lesson, and write it down. Discuss this topic with your colleagues and personal board of directors.

This is not a hard-and-fast list—remember you will keep learning—so keep adding life lessons with each valuable insight you gain.