*This article does not provide any financial advice and is meant only as a vehicle for discussion.

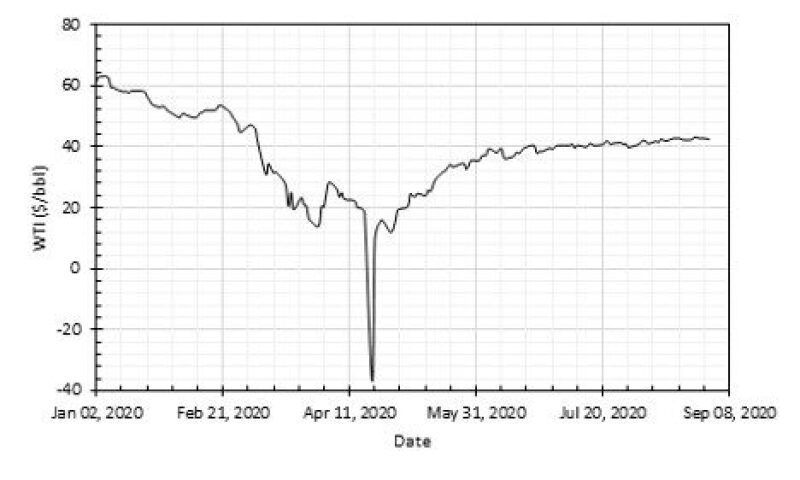

You have probably heard about the negative dip that WTI crude price took earlier this year (Fig. 1). Fortunately, prices have somewhat recovered, and the oil market is finally starting to stabilize, but the industry that revolves around this volatile commodity is still struggling.

The levels of oil stored in tankers waiting for a price hike are rising and eastern imports (mainly China and India) are slowing down. These and other factors are keeping oil prices depressed and spooking oil firms so much that some are betting on plastics as their future or opting for bankruptcy and/or acquisition.

We’re here to tell you that the picture is not that bleak; it will just take a bit longer for things to recover.

How can we say that when oil firms are dropping like flies? To be fair, it’s not just oil and gas that is suffering. As many as 492 companies declared bankruptcy this year through 20 September, according to an S&P Global analysis of public companies and private companies with public debt. The oil and gas sector, with 60 fillings over the same period, accounts for 14% of companies or 2.34% of the S&P 500 in market cap (and about 5.2% of S&P 500 companies).

So far, most of the bankruptcies in oil and gas are concentrated in the US, particularly among shale producers which boomed in the 2010s, taking advantage of rising crude prices and cheap capital. The biggest victim in the first half of 2020 was Chesapeake Energy, a shale giant that declared bankruptcy with more than $9 billion in debt. Of course, as prices dropped, many heavily leveraged companies have started to run out of options (Table 1).

Table 1—Bankruptcies in Each Sector in North America in 2020

Company Type | Q1 Bankruptcies | Q2 Bankruptcies | Q3 (Only July) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Oilfield Services | 7 | 11 | 7 | 25 |

Oil and Gas Producer | 5 | 18 | 9 | 32 |

Midstream | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

Total | 14 | 30 | 16 | 60 |

Source: Haynes and Boone, LLP.

Is COVID the Culprit?

But wait! Why is this happening? It’s COVID-19, isn’t it? Well, it’s true that COVID-19 hit the markets the hardest in March, right as the OPEC+ deal collapsed, and Russia and Saudi Arabia engaged in a price war. But the industry was in a bad shape before all of this happened. For instance, from 2014 to the end of January 2020, before the pandemic had hit the markets, the S&P 500 was up 76% while the XOP (a leading S&P oil and gas exchange-traded fund) was down 72% [author’s calculations].

So, if companies can’t rely on the public market to raise equity financing, they have to shift to debt —just like the coal industry before them. The thing is that the public markets don’t necessarily trust their debt either, leading some firms to try private equity, private debt, and commercial loans.

In theory, that’s fine—until you realize that sometimes the loans come due during a downturn and they need to be refinanced. For example, the combined Occidental and Anadarko deal was worth about $80 billion when the deal was announced; it is now worth just $12.1 billion while debts are still worth the same and interests have to be repaid. This means that even after the pandemic-driven turbulence is behind us, there will still be companies facing major problems on their balance sheets.

Very Different Players

Okay, so it has been brewing for a while. Well, yes. But not every oil and gas company is the same. In fact, the industry is filled with very different players. Let’s look at a very interesting profitability measure: company earnings per employee (for 2019). So, we have firms like NRG that earned $970,000 per employee and firms like Chesapeake that earned -$134,000 per employee—yes, that is a negative sign right there. In fact, the industry has nine companies in the bottom 20 when ranked by earnings per employee, not a feat to boast about. But, if we consider averages, the energy sector sits third among the most profitable per employee—at $86,000—only behind financials and tech.

But How Can That Be?

In summary, it’s about corporate structure and truly understanding their business model. We have plenty of shale producers at the bottom, but we also have some among the top, so it’s not just the case of "the high breakeven price.” Lots of industries work in similar conditions and they’re fine. In this case, it’s mostly because of their business model.

The idea is that you develop the reservoir and then you can start producing, or you can take that property that you explored and developed and flip it to a bigger company. Since this required a lot of upfront capital, a system of reserve-based loans was established to offload risk. After all, the oil was still going to be there to be produced, right?

Well, yes, but it’s not that easy. Many unconventional wells see their production fall by more than half in their first year of operation. And you know what the owners do? They continually drill new wells to compensate for this loss of output without adding to their total production. They’re getting loans to drill wells, promising that these wells will provide hefty profits for their lenders. In the first year it looks amazing but then it stops; then they have to get another loan to drill more in order to pay back the first loan with the promised output.

This whole thing seemed to work for some, as oil and gas companies, left and right, plunged over $156 billion into corporate takeovers and land deals during the second US shale boom (2016 and onward), in a massive bet that good times would continue and crude prices would rise. But all those bets went south when the price no longer kept propping up that flawed business model. And so, when the dominoes fell, they fell hard, and they fell all across the board.

Like 2016, Only Different

But then we recovered! So, does this mean that this time it will be like 2016? It definitely could. The promise of future returns might lure investors again in a wave of mergers and acquisitions just like it did after the first boom when prices pulled back sharply from 2014 to 2016.

But things are also different this time. For instance, banks are writing off or selling oil and gas loans, which is very rare. This is mostly due to the support provided by the COVID stimulus. Newly acquired/freed capital enables banks to either increase provisions for the bad loans or absorb losses from selling them, both of which trigger write-offs—especially when combined with the goal of cleaning up their balance sheets in order to issue new loans without scaring investors or deteriorating their credit rating. Essentially, the bank can allocate its stimulus-sponsored productive resources to new lending, instead of becoming an asset-management company of “bad/distressed oil assets.”

A basic understanding of corporate strategy might provide a viable direction for an industry with limited competitive differentiation, deep cycles, and a high degree of capital intensity, along with newly available cheap fed financing: consolidation.

They Want It Now

But if consolidation is what is required, then where are they? Well, the last crash (the one after 2014) did spark a wave of consolidation, but that doesn’t mean that this time around it should happen again. This time, investors are no longer interested in growth or probable future returns —they want/need cash and they want it now. This time around, everyone has been impacted to some degree so everyone is at a disadvantage. Caution will probably be the name of the game for everyone—for sellers, buyers, lenders, and shareholders. As such, oil companies are cutting their budgets to preserve cash and survive, not to spend it on buying more companies.

That said, we still have seen some movement. For instance, Chevron’s acquisition of Noble Energy (which is interesting in its own regard: it really began as a sale of a 50% stake in the Leviathan gas project but ended with the whole company—for which Chevron paid $13 billion when accounting for bought debt) or BP selling some of its assets to Ineos and Hilcorp. This is nowhere near normal, as asset-deal value fell by about 57% and corporate deals by a whopping 94% from H1 2019 to H1 2020 (this, considering that 2019 was already a slow year for oil and gas mergers and acquisitions).

This pandemic has created a tremendous amount of uncertainty, so prices are going to almost definitely not be aligned with value; that’s an environment in which striking deals is difficult. Besides, most shale companies haven’t really proven that they’re able to make money with what they have. Would you buy their unproven assets?

Of course, acquisition might be the sole lifesaver for some companies, and they might “fire sale” their assets, but there are a lot of things to consider—besides it’s cheap. Liquidity, solvency even, is going to be a real issue going forward, so balance sheet strength (especially before the crisis) is extremely important. Other factors, like cash flow and margins, that give an indication of how quickly a return to profitability is possible, should also be considered. If you don’t, you might end up on the list of the myriad M&A deals since 2016 that haven’t generated positive returns.

The big bucks are going to be made by finding the companies that have been caught up in the selling despite not fitting the profile of companies with liquidity/solvency problems in their foreseeable future. For example, a company like Diamondback Energy, with a debt-to-equity ratio of around 40 and a current ratio (current assets over current liabilities) of 0.69, would be way better than one like Apache Energy with more than 274 debt to equity and a current ratio over 1.

Fork in the Road

Wow, ok. So, what plagues are coming our way in the future? One thing is for sure, oil is going nowhere for the foreseeable future. Even if the rate of new electric cars purchased increases, given the frequency of car purchase, it would take about 20 years to reach 25% of the cars on the road unless there is a hard policy update by some governments (also see Electric Vehicle Outlook, EV Survey Report).

The same goes for other oil-based products. Oil and gas—especially gas—for power generation are also not going anywhere any time soon, despite the green push.

However, one thing to keep an eye out for is the fact that the industry is facing a fork in the road regarding capital allocation. Some might see their (perceived) undervalued shares and think that buying back shares might be a better investment than drilling new wells—after all, their mandate is value creation, not growth. Others might believe that their stock price is overvalued and will try to go for acquisitions using equity when possible, since it’s good for the balance sheet. And still others might try to protect dividends, because they believe that investors will reward the stable income in a downturn by purchasing their shares.

But I think that they’re missing a big consideration: in this environment; companies should make investments focused on long-term value creation for both the shareholders and the stakeholders; they should focus on spending their cash on things that invite praise and not on finger pointing. Let’s explore the case of a company that decides to allocate capital toward generating reasonable full-cycle cash-on-cash returns, focused on maximizing free-cash flow and investing back in the core business (employees and all).

If they do so, when OPEC+ spare capacity decreases and excess inventories have already been consumed, shale oil will be required to balance the oil market, and that’ll be their moment to shine. If they do so, they’ll be ready to allocate more capital to drilling wells when the relative returns justify it.

Let’s hope they take the road less traveled by.

[The article was sourced from the author by TWA editors Nazneen Ahmed and Bita Bayestehparvin.]