What is energy transition? Is the petroleum industry in its sunset? Are petroleum engineers a dying breed? A brief look in history can help us “see” the future objectively. The data for all plots shown in this article was taken from BP Statistical Review of World Energy. Thoughts that follow are my own.

Deciphering the Past: What Actually “is” Changing?

The US Civil War starting in 1861—only 2 years after the first oil discovery on American soil—led to an oil shortage that caused a massive price surge, which was almost completely offset by a race for production, plunging the oil price to $0.10 per barrel (Yergin, 1990). By the end of the Civil War in 1865, there was widespread fear of oil running out. Since then, multiple oil crises led to similar “we are running out of oil” rhetoric, notably in 1973 triggered by the Arab oil embargo, in 1979 following the wake of the Iranian Revolution, and in 1990 in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait (Yergin, 1990).

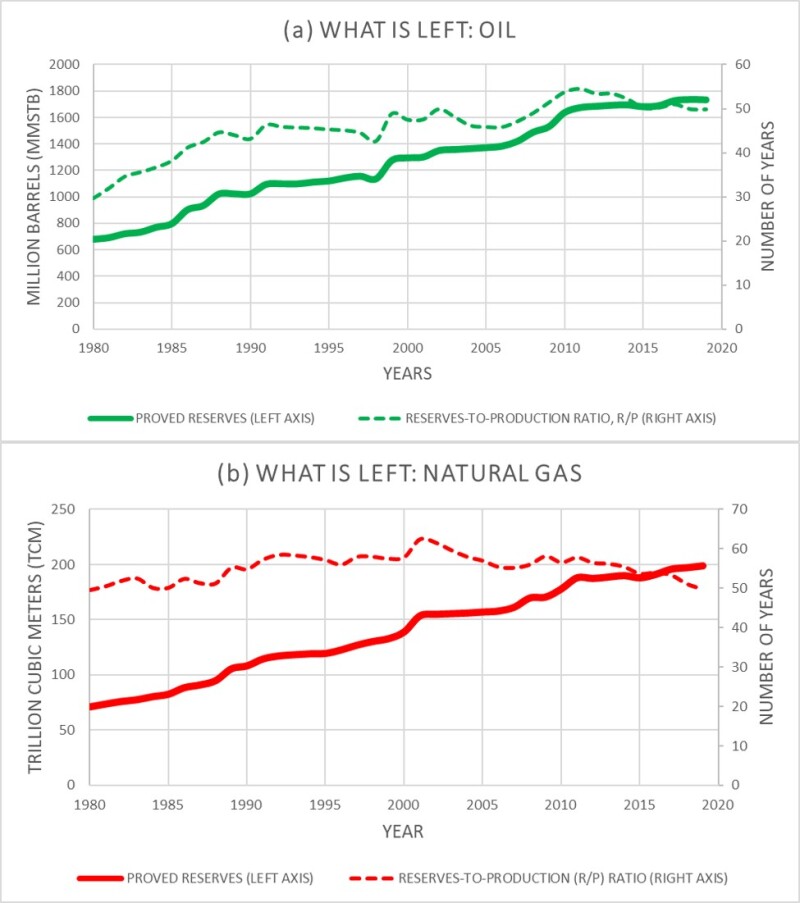

Oil and Natural Gas: What is Left? Flawed predictions of future oil supply often led to public bewilderment. As petroleum engineers, we know that oil and gas are finite resources produced from depletable reservoirs, which will inevitably peak. Nevertheless, this “peak” which does not seem to be happening anytime soon will not have the disastrous, abrupt impacts often suggested.

As petroleum engineers also, we know that the term “reserves” constitutes a variable quantity which represents the amount of the oil and gas resources (which is in contrary a fixed and virtually-impossible-to-know quantity) that are commercially recoverable. This implies that oil and gas reserve amounts may fluctuate following changes in the oil price, the technology available for their exploitation, and the prevailing political environment. Figs. 1a and b show the world’s total proved oil and natural gas reserves variation from 1980 to 2019, along with the variation of the reserves-to-production ratios (R/P) for the same time period.

Interestingly, both oil and gas reserves increased by 154% and 181%, respectively, over the assessed 39-year period. This alone should render the idea of rapidly depleting and diminishing petroleum reserves far from true. Furthermore, the R/P ratios (also dependent on the fluctuating prices) do not seem to display a worrisome drop, especially for the case of oil.

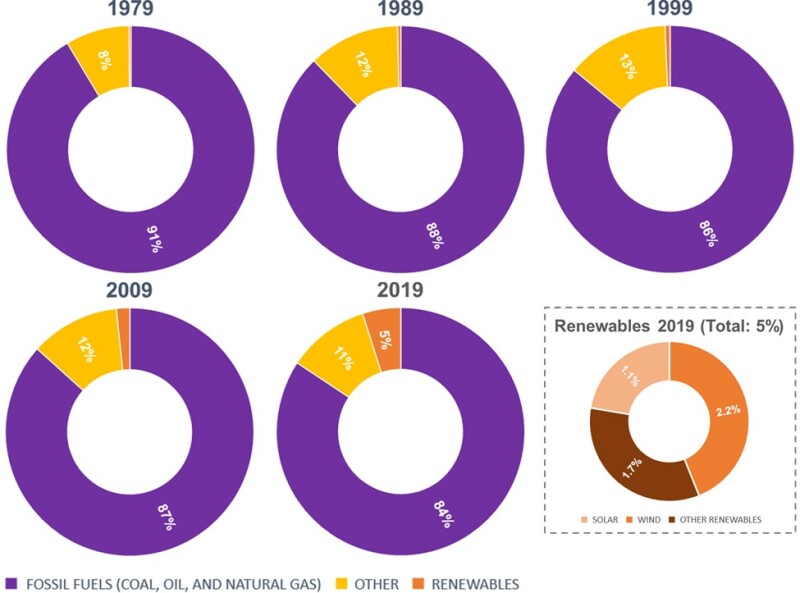

Powering the Globe. Fig. 2 shows the breakup of the world’s energy consumption at the end of each of the past four decades (1970s to 2010s), from 1979 to 2019. The purple section indicates the portion of the world’s energy consumption provided by fossil fuels, which hold the lion’s share ranging from 84%–91% over the years examined. Orange indicates the energy consumption provided by renewable sources, which reached 5% in 2019. Out of this, 3.3% is derived from solar and wind. This 3.3% merely scales with the investments granted for research and development and infrastructure for these resources over the decades by the government and private sectors.

Albeit rising, the portion occupied by solar and wind remains unscalable to the growing global energy needs due to their low energy density and intermittence, which makes them unreliable. Figs. 1 and 2 do not seem to spell a replacement of fossil fuels in relative or absolute terms in the foreseeable future.

| ▶Fossil fuels still dominate the world’s energy mix and there is plenty left. |

The Future—A Century of Natural Gas?

Natural gas is the cleanest of all the hydrocarbon energy sources with the lowest carbon-to-hydrogen ratio, providing high energy-conversion efficiencies vis-à-vis power generation. Plentiful gas resources have been discovered that are yet undeveloped with the breakdown price at which those projects start becoming profitable, being much smaller than for alternative energy sources. Despite the 2014 price collapse bringing many natural gas projects down to their knees, the pre-established trend toward natural gas becoming the premier fuel of the world economy is not easily reversible.

The transition to natural gas for the energy industry is a challenging prospect. Given its abundance, economic, and environmental benefits, especially as the cost of carbon emissions starts having a bigger impact around the world, natural gas should likely be the predominant fuel of the “new energy” economy. Nevertheless, a switch to natural gas as the primary energy resource will not happen overnight.

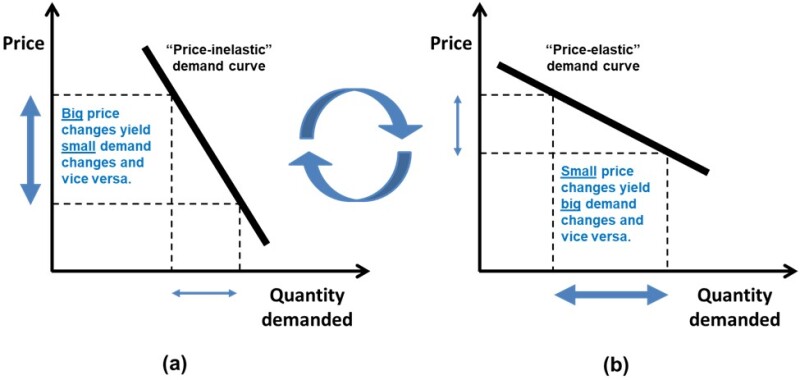

The Price-Elasticity of Natural Gas Demand. As any (energy) commodity, the demand for fossil fuels is said to be “price-inelastic,” meaning that changes in the price do not trigger significant demand shifts (Fig. 3a). This is primarily due to lack of close alternatives. As additional infrastructure aiding the transition to natural gas starts coming on line, the demand for natural gas is expected to start becoming more “price-elastic” (Fig. 3b), enabling it to capture market-share from oil and coal in the transportation and power generation sectors, respectively. Once this transition is over and the dynamics in the global energy markets stabilize, the natural gas demand is expected to revert back to its price-inelastic state (Michael, 2014).

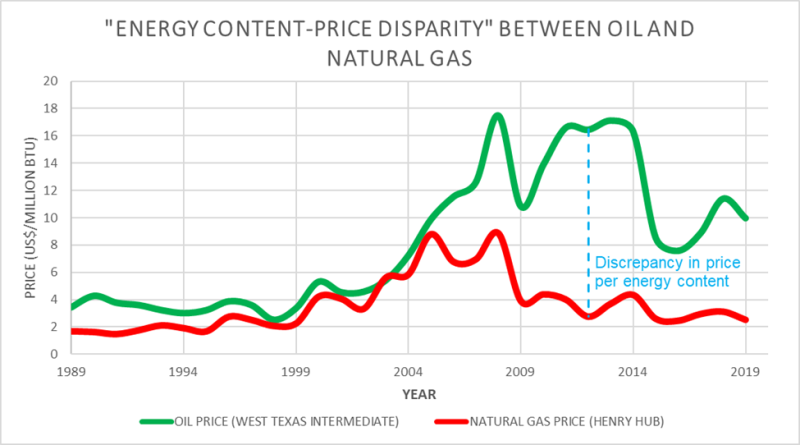

Disparity Between Energy Content and Price for Oil and Natural Gas. A crucial difference between natural gas and oil is the price disparity between the two in terms of their energy content (Agin, 2011; Michael, 2014). This disparity started becoming evident in the mid-2000s and was maximized during the years of the American “Shale Revolution” (Fig. 4). Driven by technological challenges and resource availability, this disparity provides natural gas with opportunity for rapid growth and penetration in the transportation sector, directly or through electrification.

| ▶Natural gas is not a “transition fuel,” but the fuel the world economy has to transition into during the 21st century. |

In a world where year-after-year more and more oil and gas are consumed, a bullish outlook on the market for “oil and gas workers” should not be matter of debate. However, for petroleum engineers, a steady oil and gas job market may not necessarily warrant robust employment opportunities, particularly straight after graduation.

Petroleum Engineering—Expanding Frontiers or Building Expertise?

Graduate entry-level industry placement dominates career choices of ambitious college applicants. Decreases in student enrollment in petroleum engineering (PE) programs reported by various universities (Feder, 2019; Ruiz, 2019; Heinze et al., 2019) has posed questions about the future of the PE discipline, well in its post-centennial years (the University of Pittsburgh established a PE department in 1910). Ahead of the trend, the Imperial College of London has recently suspended its PE master’s program following the 2021-22 academic year.

Nevertheless, while these enrollment drops were generally “blamed” on the low oil and gas prices, a less considered factor is the market “power” of the PE degree, ipso facto controlled by the reputation of the PE academic programs in the industry.

The typical reaction of PE academia to the reality-check of the enrollment drops, induced by a stubbornly suffering industry placement, seems to be expanding the frontiers of PE programs for preparing their students for non-oil and gas jobs (e.g., in geothermal, carbon sequestration) and even non-energy-related jobs (e.g., finance, data sciences) per Feder (2019) and Ershaghi and Paul (2020). Perhaps the focus should better be on ensuring that more PE-oriented, upstream oil and gas jobs go to PE graduates, rather than non-PE candidates, by deepening the relevant skills taught in the classroom. If every PE graduate comes out of his or her program with a skillset which is superior to that of his or her competition, he or she will be the preferred choice for a PE-oriented job. That should be the goal.

| ▶The foundation for career longevity in our discipline is in enhancing the relevance of the skills and expertise taught in the classroom, based on industry realities. |

References

Ershaghi, I., and Paul, D. L. (2020). Engineering the Future of Petroleum Engineering and Geoscience Graduates. In SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition. Society of Petroleum Engineers. Oct. 19. https://doi.org/10.2118/201423-MS

Heinze, L., Menouar, H., Watson, M. et al. (2019). Petroleum Engineering Enrollment: Past, Present and Future. In SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition. Society of Petroleum Engineers. Sept. 23. https://doi.org/10.2118/195908-MS

Michael, A. (2014). Economic Implications of the Current Geopolitical Forces Vis-à-vis Hydrocarbons on Global Energy Markets. Society of Petroleum Engineers. May 19. doi:10.2118/169832-MS

Yergin, D. (1990). The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power. Simon & Schuster.