The primary purpose of this article is to relate the transfer of technology from a country with expertise to the native country of a foreign-educated student. The secondary purpose is to clarify points not obvious to and yet ignored by incoming foreign students and help prevent future disappointments. This is applicable to foreign petroleum engineering students in the US, arguably the “home” of oil and gas industry and relevant technology. A certain amount of generalization is made. The thoughts that follow are my own.

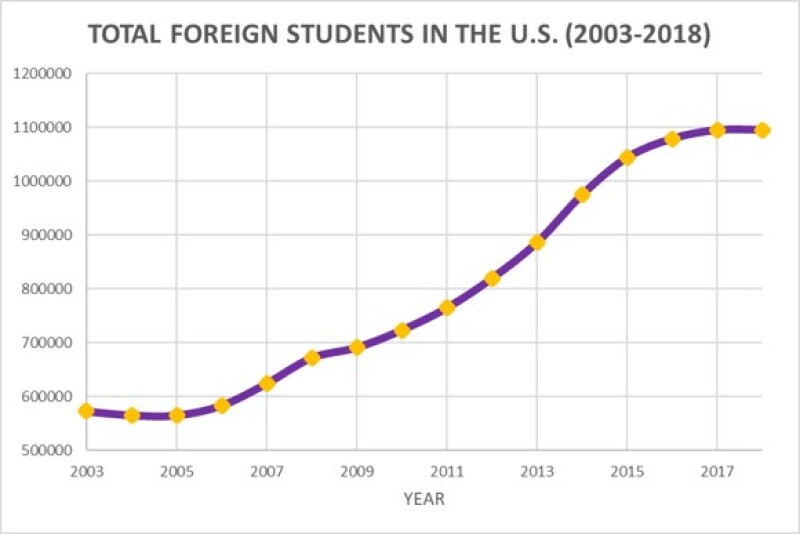

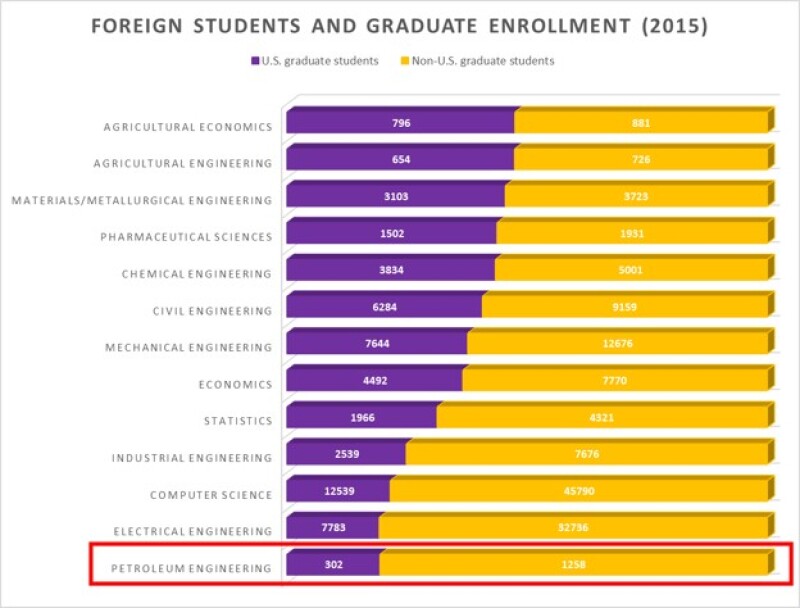

Theoretically, the engineering and hard sciences student body worldwide is a major medium for technology transfer. In the US, the citadel of higher education, foreign students constitute a large and growing portion of the graduate student body (Fig. 1). This is especially true in petroleum engineering (Fig. 2), where more than eight out of ten enrolled graduate students in universities are foreign nationals.

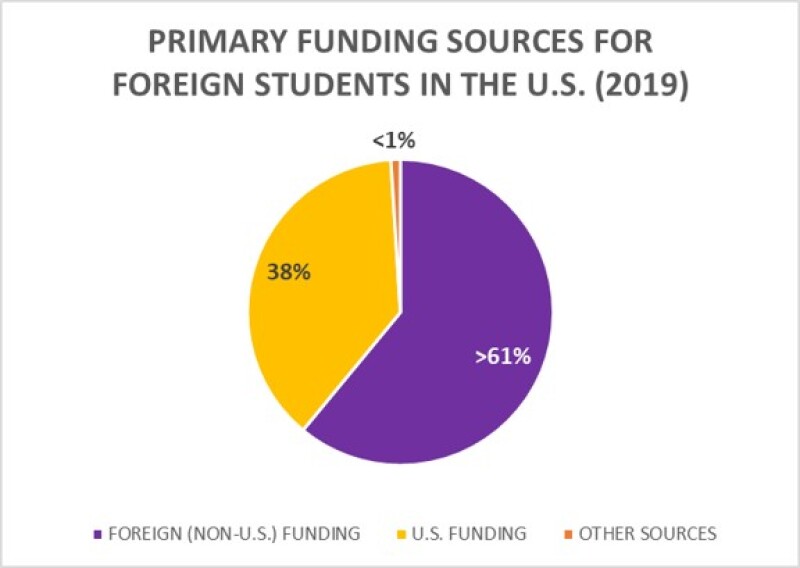

The funding for those foreign students is either derived from personal funding, various grants offered by governmental agencies (e.g., the Fulbright Program, National Science Foundation, Department of Energy), or from members of the private sector (corporations, individual donors, etc.). The majority of the primary funding of foreign students enrolled in US universities is sourced from outside of the US (Fig. 3).

When an incoming graduate student leaves his or her native country, the inherent assumption is that upon return he or she will bring top-notch expertise in his or her specialty as well as technological knowhow necessary for industrial innovation and growth. This transition is often much harder than anticipated due to differences in the needs of the economies of the students’ native countries with that of the US (or any other nation from which the graduate obtained his or her degree from). Many times, these nations do not have the capacity to develop these technologies (especially Third World countries), which renders zero returns to the graduate’s investment. Contrary to repatriated foreign graduates, native graduates tend to enjoy a relatively smoother transition into the industry from academia.

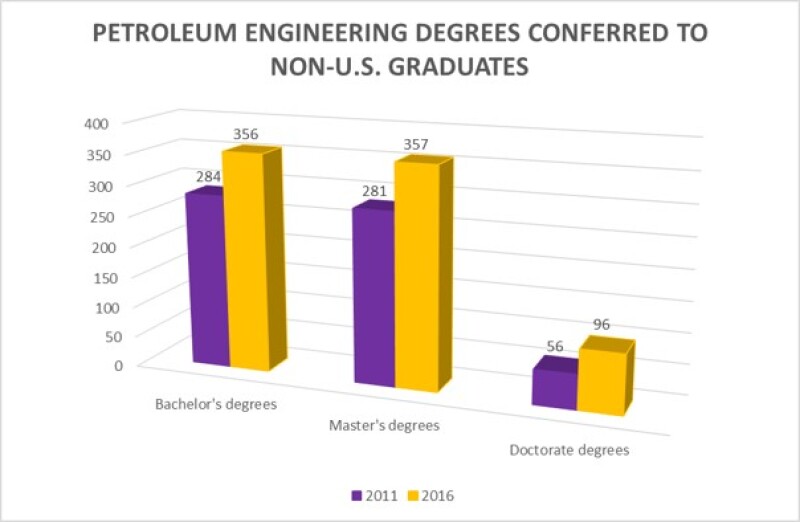

Foreign students represent a group more selective than the average native student. Some foreign students come from societies where attending college is an accomplishment, especially when doing so in the US. Owing to their backgrounds, the foreign students’ scope is generally narrower vis-à-vis their career path and objectives. They are less open to changing their major during their stay in college and target a shorter list of potential employers, compared to native students. In petroleum engineering, according to the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities’ 2018 Status Report on Engineering Education (Anderson et al., 2018), the number of bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorate degrees conferred to non-US graduates have increased between 2011 and 2016 by 25.4%, 27%, and 71.4%, respectively (Fig. 4).

Nevertheless, the average foreign student arrives at a university unprepared, encountering an academic system with characteristics which eludes him or her. Many times, foreign students are alien to their future professions and because of that they cannot set clear-cut goals.

Even to this day, universities are not adept in preparing foreign students for careers within their native countries—a highly unrealistic task, per se. However, one would expect these engineering and hard sciences departments to be responsive to their foreign students’ needs, considering that these students fill spots left behind by native graduates when they head into the industry. Unfortunately, whether academia is the optimal mode for introduction to local technology is questionable (Badruzzaman, 2003).

Consequently, this puts foreign students in a “no man’s land.” While at school they are facing the shortcomings of their education, and after graduation they must either go home inadequately trained or attempt to stay and compete in a market which is inundated with local manpower. During the technological boom of the 1940s, most foreign students in the US could stay following graduation. Nevertheless, this phenomenon has long been tapered off and so did demand for foreign graduates for whom it is virtually impossible to compete in a market oversupplied with US graduates.

Drawn by reputation, foreign students especially try hard to enter one of the most prestigious universities in their discipline. Nevertheless, departmental rankings may be quite indifferent not only to the student’s prospects, but also to the realities of their profession. The fact that a department is considered No.1 does not make it a good place for a foreign student to attend; it may very well be one of the worst.

The system of educating foreign students in countries of high expertise in their educational discipline is clearly suffering (Economides, 1978; 1979; Franklin, 2015), resulting in industry placement challenges that may not be too obvious to the newly arrived foreign student. For foreign students, securing post-graduation employment has become quite a formidable task. Adding to this, when the need for foreign expertise arises, a nation tends to opt for experienced foreign personnel rather than repatriated graduates educated in that specific foreign country.

Direct training of local people by foreign corporations may be perhaps a more efficient mode of technology transfer (Economides, 1979; Green et al., 2020), especially in the era of distant and remote learning. Bilateral agreements of governments with foreign corporations may promote this at a lower cost and with less risk associated with the lack of returns from a foreign-educated graduate. This way, foreign corporations can also receive additional income resulting in a true “win-win” situation.

References

Anderson, E. L. et al. (2018). Association of Public & Land-Grant Universities, p. 41, The 2018 Status Report on Engineering Education: A Snapshot of Diversity in Degrees Conferred in Engineering.

Badruzzaman, A. (2003). Critical Success Factors for Technology Transfer: Sharing a Perspective. Society of Petroleum Engineers.

Bustamante, J. (2020). educationdata.org/international-student-enrollment-statistics. International Student Population & Enrollment Statistics [2020]. EducationData, 8 Nov.

Economides, M. J. (1978). Foreign Students Face Problems. The Stanford Daily, 25 Sept.

Economides, M. J. (1979). Transfer Technology. The Stanford Daily, 12 Feb.

Franklin, H. (2015). International Students Struggle to Find Jobs After College. The Reveille, The Daily Reveille, 12 Apr.

Green, T., Hajri, N., Ortiz, S., and Nelson, J. (2020). A Case Study: Applied Knowledge Transfer. International Petroleum Technology Conference. Jan. 13, doi:10.2523/IPTC-19599-Abstract

McElroy, W. (2015). The Brain Drain, Gain and Retain. The Independent Institute, 1 Jan.

Redden, E. (2017). Foreign Students and Graduate STEM Enrollment. Inside Higher Ed, 11 Oct.