Confused between Oil Options and Oil Futures? Options contracts give holders (of long positions) the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell the underlying asset. The most a crude oil option holder can lose is the cost of the option (premium) that is paid to the option writer (seller). On the other hand, Futures contracts carry an obligation and are physically settled. Futures traders can lose the entire position during an adverse movement of the underlying price. Start your journey to investing in oil markets here. Also check out this quick read on the complex world of oil markets and trading. |

On Monday, 20 April, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil front-month futures traded on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) were priced in negative dollars per bbl for the first time since trading began in 1983. At about 2:30 pm ET, WTI traded as low as −$40.32/bbl; prices remained below zero for part of the following trading day.

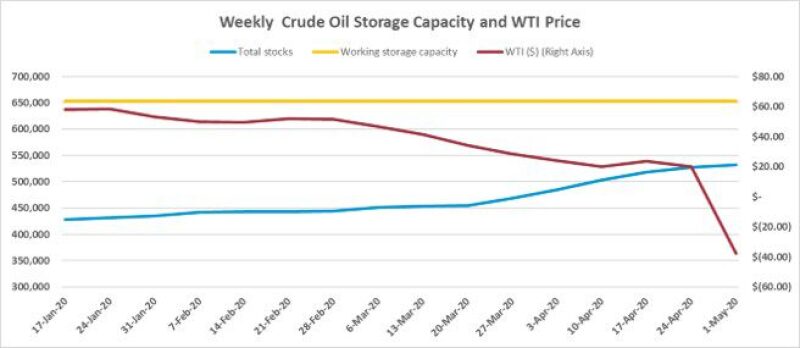

In addition to market surplus generated by Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), travel restrictions and general economic slowdown because of the COVID-19 mitigation efforts contributed to these low prices. The scarcity and high cost of available crude oil storage incentivized several market participants to close their positions before having to physically settle their contracts. Some contract holders resorted to selling their futures contracts at negative prices, in effect paying a counterparty to allow them to exit their positions.As the prices fell, the total crude oil stock increased 24% from around 428 million bbls in third week of January to 532 million bbls in first week of May.

As per the US Office of Fossil Energy, stockpiling oil in artificially created caverns deep within the rock-hard salt costs historically about $3.50/bbl in capital costs; storing oil in above-ground tanks, by comparison, can cost $15–18/bbl (or at least five times the expense) in capital costs. The operating costs to store the oil was already high and it increased further as a result of current prices. The cost of leasing 100,000 bbl of crude oil storage for one month in the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port was roughly $7,000 before April 20; that cost rose to approximately $55,000 in May (bbh.com).

The impact of these low prices was immediate. Many companies announced production cuts. The largest cuts announced so far [as of writing] came from ConocoPhillips which said in addition to its Canadian oil sands projects that it is shutting in nearly the entirety of its US onshore position—some 2,400 wells, representing about 165,000 B/D. A projection from commodity researchers at JP Morgan Chase suggests as others follow suit these curtailments may reach 1.5 million B/D by June. While the larger producers might be able to sustain this downturn, many small and mid-sized producers might be at a higher risk. They simply may not have enough resources, including marketing capabilities, to keep producing at a low price. Many producers will be forced to halt production. By halting production, producers might survive the downturn by saving money but the long-term impact of well shut-ins need to be considered.

Fig. 1—Weekly Crude Oil Storage Capacity and WTI Price. Total stocks include stocks held in above-ground tanks, underground storage, and pipelines at refineries and tank farms plus stocks in transit by water and rail. Working storage capacity as of 30 September 2019.

When selecting the candidates for shutting in wells, the gut instinct would be turn to the lease operating statement (LOS) and select the wells with the highest expenses or lease production. This could be a good decision maker in some cases, for example, if you are working with high-water-cut wells since you do not have to cover the water disposal costs now. The actual situation is more complicated than that. Some wells are held by production, meaning if the well ceases to produce a minimum paying quantity, the producer can lose the lease. There are numerous subsurface challenges to be considered as well.

If a marginal well is shut-in for a long period of time, it may either not return to production or can become uneconomical to produce due to high lift expenses. On the other hand, if a reasonably producing well is shut-in for a long time it can have its own consequences. Permeability variances within the producing set of inflow points (formation layers flowing into the wellbore) create groups of lower-pressure, higher-permeability zones, and groups of higher-pressure, lower-permeability zones. During production, the flowing bottomhole pressure will usually be low enough to maintain flow from all zones, but when flow is stopped, crossflow from high pressure to low pressure zones may start. Mixing of gases, oils, and waters from different zones can create many problems, some of which are extremely difficult to remove. Moreover, if a well is shut-in for a long time, the mixed fluids could lead to buildups of paraffin, asphaltene, or other emulsions both inside fractures and at the perforation.

The selection of the right candidates to shut-in is not straight-forward and cannot be standardized easily. In an attempt to list the various nuances involved, JPT recently published a synopsis of technical considerations for Managing Risk and Reducing Damage From Well Shut-Ins. The authors noted that due to the complexity of this topic, the list of technical considerations is not exhaustive. While this list can act as a starting point for conducting your study and selecting “good” candidates for shut-in, the topic remains subjective—there is no one size fits all solution to this. The well doctors need to talk to their wells, understand their heartbeats, and prescribe a solution accordingly.

On another note, if the current economic trends continue, wells across the board—low, medium, or high producing—will be affected since shut-in of lower- or medium-producing wells will not remove enough oil from the system to fix the storage issue.

Check out the following articles to dive deeper into this subject:

Evaluating the impact of market variability of reservoir behavior and economics

When does a longer shut-in lead to a larger radius of investigation?

Effect of frequent well shut-ins on well productivity: Marecellus shale case study

In brief, consider the analogy of the real estate market for shutting in wells. If a house does not have a tenant, you would simply lock the house. However, in the oil and gas industry turning the tap off is akin to demolishing your house if you do not have a tenant. That house could have costed from $5-10 million to build. You are not just turning the well off, you are killing the well. You may be shutting off the economic life.

Vikrant Lakhanpal is a member of the TWA Editorial Committee. He works as technology integrator at Proline Energy Resources, based in Houston, where he focuses on developing transformative solutions by combining subject matter expertise and technology. He was previously a production engineer focusing on brownfield development, and is also actively involved in the acquisition and divestiture market. Lakhanpal volunteers as assistant director at Well Engineering Research Center for Intelligent Automation at University of Houston. He holds a master’s degree in petroleum engineering from University of Houston and a bachelor’s degree in petroleum engineering from University of Petroleum and Energy Studies, India. Lakhanpal has being a part of SPE since 2010 and has held various volunteer positions at SPE globally.