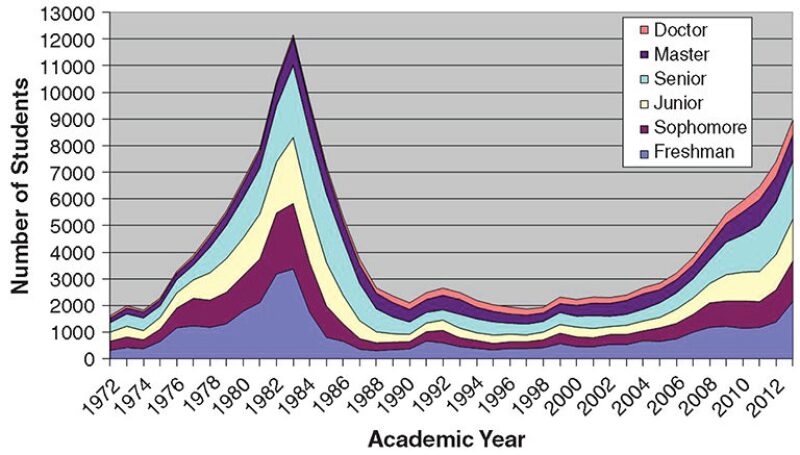

For many years, professor Lloyd Heinze of the Texas Tech University Petroleum Engineering Department has been collecting US petroleum engineering enrollment data from all of the department heads in the country. These data have always been enlightening, but the current trends are more than enlightening, they are cause for concern. Fueled by the strong demand for petroleum engineering graduates at all degree levels for the past several years, petroleum engineering enrollment in the US, particularly at the undergraduate level, is increasing in a manner similar to the period between 1976 and 1982.

The enrollment data in Fig. 1 is alarming, and each university needs to understand the industry situation to determine its proper course of action. In our opinion, engineering departments cannot continue increasing enrollment at the current rate or they most likely will experience a sudden decline, as they did in the mid-1980s. At some point in the near future, enrollment needs to level off and grow at a much lower rate, if at all.

Those of us who have been in the business since the 1970s remember the enrollment “mountain” shown in Fig. 1 that peaked in 1984. For those of us in academia, the most significant part of this mountain was the incredibly fast rate at which enrollment declined, causing considerable stress in all departments and the closures of some departments. For petroleum engineering students graduating in those years, the implications were dire, for there were no jobs in the industry for a large number of them.

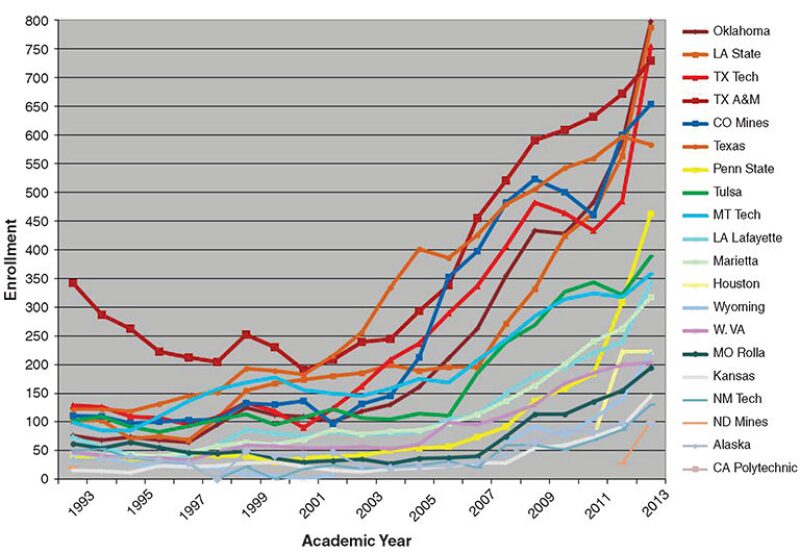

A closer examination of the past few years helps to understand where the growth is occurring. Fig. 2 shows bachelor of science degree enrollments in petroleum engineering departments in the US. Of particular interest is the change that has occurred in just the past year.

Between fall 2011 and fall 2012, the number of freshmen in petroleum engineering programs in the US grew from 1,388 to 2,153, a 55% increase in one year. The enrollment pressure we are experiencing at Texas A&M suggests that there will be another increase in freshman enrollment in 2013. We are rapidly heading toward having more than 2,000 BS petroleum engineering graduates per year in the US. So far, essentially all of our graduates have been receiving job offers, but there is a concern that the job market may not grow as fast as enrollment and graduation rates.

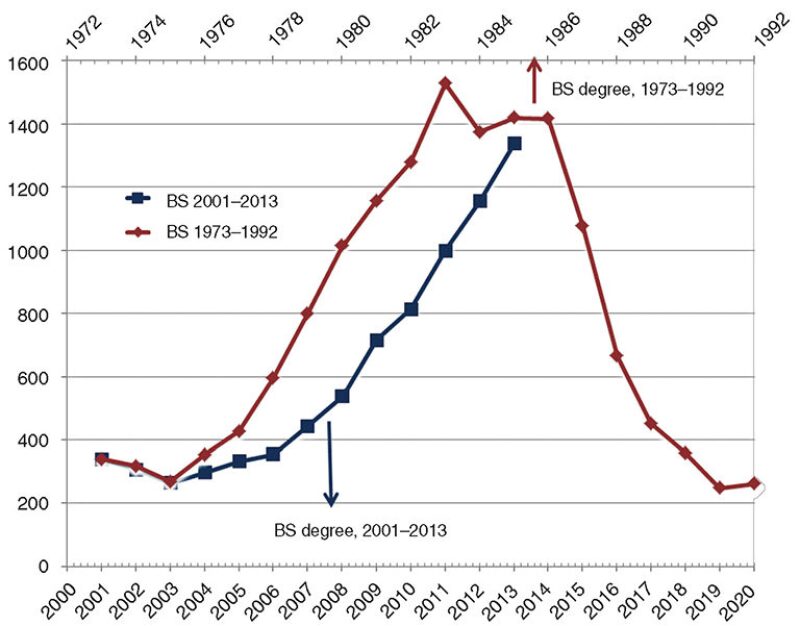

A direct comparison of current graduation rates with the last peak is instructive. Fig. 3 compares the number of US BS graduates from 1973 to 1992 with the number of graduates from 2001 to 2013, with 2001 overlain with 1973.

The resemblance is remarkable, with the growth rates from the past 4 years being almost identical to those leading up to the peak in the 1980s. Considering the number of freshmen in 2012 and the number of students who are transferring into petroleum engineering at the sophomore and junior levels, we are headed to a peak substantially higher than that seen in the 1980s. The 1980s peak graduation rates lasted for 4 years because when the job market weakened, there were already four large classes of petroleum engineering students in the pipeline. Once this bulge graduated, BS graduate numbers declined rapidly, as enrollments had begun to do a few years earlier.

So when will the next peak in petroleum engineering enrollment occur and why? Enrollment, and eventually numbers of graduates, will decline if and when a significant softening in the petroleum engineering job market occurs. The job market could weaken if and when a significant decline in oil prices occurs or the number of petroleum engineering graduates exceeds what even an expanding industry can absorb.

The Pessimistic View

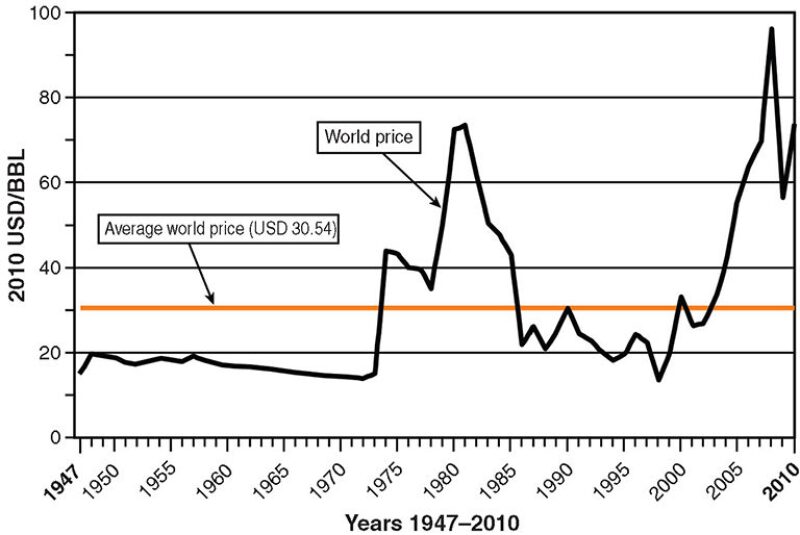

There are predictions that the increasing energy demand from emerging economies around the world will sustain high oil prices indefinitely, but history tells us otherwise. The oil and gas business is a lucrative and robust industry—extended periods of high prices lead to rapid development of new oil and gas reserves, and resulting rapid increases in production levels, which eventually lead to lower prices. We are currently in a period of rapid development of new production worldwide, not just in the unconventional reservoirs of North America. It is also instructive to remember that the average price of crude oil from the mid- 1940s to the present day has been about USD 30/bbl in 2010 dollars (Fig. 4). So if history repeats itself, we could be in for a crash in the job market at some time in the next few years.

An Optimistic View

Another view of the job market is that the “shale revolution” will span the globe in the next 20 years. Developing shale (or tight) reservoirs requires drilling tens of thousands of wells per play, rather than the hundreds required to develop conventional reservoirs. That means we need more rigs, logging trucks, fracturing spreads, and yes, more engineers and geoscientists—a lot more. Combining the need for more engineers with the retirement of the baby boomers, the job market could be adequate for the recent increase in enrollment—if and only if enrollment eventually stabilizes at a sustainable level. For sure, it cannot continue increasing at the current rate.

A Global Business

One factor to consider is that the oil and gas industry is a global industry. International oil companies (IOCs) and national oil companies (NOCs) must hire nationals in the countries where they operate. As such, the demand for petroleum engineers should be viewed in a global sense. The IOCs and NOCs will hire more from local universities and fewer from US universities as unconventional oil and gas plays spread around the world.

What can we do to mitigate what appears to be an impending oversupply of petroleum engineers? There are things that both academia and industry can do. On the academic side, petroleum engineering departments need to work with their administrations to manage the unbounded growth in enrollment that is currently occurring. Some schools are already doing this, but many are not.

At Texas A&M, we have a target maximum enrollment of 800 undergraduates, which we expect to reach in fall 2013. Regardless of the job market, our faculty size does not allow us to effectively educate an undergraduate population larger than that. The University of Texas at Austin also appears to be managing enrollment. Interestingly, these two petroleum engineering departments, which have historically been the largest programs in the country, have current enrollments that are only about half their peak enrollments in the 1980s and are no longer the highest enrollment programs in the US. Every petroleum engineering department in the US should be implementing an enrollment management plan.

What can industry do to avoid a job market collapse for petroleum engineers? It is simple: The industry can hire more of them. It is not hard to show that a petroleum engineer adds value to a company, in good times or bad.

Here is a simple calculation. Assume that it costs a company USD 300,000/year to support a petroleum engineer who has a salary of USD 100,000/year. How much oil or gas does that petroleum engineer have to produce (or prevent from declining) for that engineer to pay out for the company? At USD 60/bbl, it is about 14 BOEPD, and at USD 30/bbl, it is 28 BOEPD. Can young petroleum engineering graduates create this amount of production? If they cannot, we are not educating them well enough. We in academia have been encouraged by industry to produce more and more petroleum engineers for the past several years. When markets weaken, the industry should seize the opportunity to increase the value of their companies by continuing to grow their petroleum engineering workforce.

A. Daniel Hill, SPE, is head of the Harold Vance Department of Petroleum Engineering at Texas A&M University, and is a professor and holder of the Noble Endowed Chair in the department. Previously he served as the department’s assistant head and associate head. Hill was named an SPE Distinguished Member in 1999 and in 2008 received the SPE Production and Operations Award. He has also served as an SPE Distinguished Lecturer. Hill earned a BS degree from Texas A&M and MS and PhD degrees from the University of Texas at Austin, all in chemical engineering.

Stephen A. Holditch, SPE, retired from the Harold Vance Department of Petroleum Engineering at Texas A&M University in January 2013, and is currently a Professor Emeritus. Holditch led the department from January 2004 to January 2012. Holditch served as SPE president during 2002 and is an Honorary Member and Distinguished Member of SPE. He has earned numerous SPE awards, including the Anthony B. Lucas Award, Lester C. Uren Award, and Distinguished Service Award for Petroleum Engineering Faculty. He earned BS, MS, and PhD degrees in petroleum engineering from Texas A&M.