About 3 years ago, upstream executives at BP came together and recognized that this down cycle was not like the ones before. The moment marked the beginning of the company’s “digital journey,” one that it says is paying off in spades.

“Our industry—our sector—it fundamentally changed,” said Ian Cavanagh, the head of modernisation and transformation at BP. As a nearly 29-year veteran of the company, encompassing his entire oil and gas career, he spoke with authority on how shifting conditions have redefined what it means to be a supermajor in the 21st century.

It means taking on the controversial issue of global climate change by promising to find ways to increase energy production while lowering the overall carbon footprint. BP’s answer to this “dual challenge” includes big investments in the electrical vehicle sector, solar power, and wind power.

But more to its core, the tidal forces of volatile commodity prices meant that BP needed to go on a digital technology shopping spree to either find more oil and gas, or get it out of the ground at a lower cost.

Today’s portfolio features a growing list of in-house innovations, such as a new fiber-optic interpretation company that BP is spinning off to the outside world and a team of robots that will soon assume a lead role in offshore inspections. BP reported in January that its new seismic device called Wolfspar led to the discovery of more than 1 billion bbl of oil in place at its Thunder Horse field in the Gulf of Mexico.

Dozens of other technology developments have come together with outside help, including a major digital twin project in the Gulf of Mexico and an artificial intelligence program that aims to prevent sand production problems in the Caspian region.

But no matter how high the technology stack grows, a digital transformation ends up being a people problem. BP is keenly aware that the modern workforce—now dominated by a tech-savvy millennial generation—has expectations for management that go beyond the size of the paycheck. They want to work at companies that move fast and are willing to kill off the status quo best summarized with the phrase “We’ve always done it that way.”

Cavanagh argues that BP has answered this call. “To retain and attract the best talent in the world, in our industry and outside our industry, we had to change several things about how we do work,” he said, noting that without getting this human element right, “we’re in trouble.”

Transforming BP meant that executives would have to put their weight behind an effort to root out the traditional oil and gas decision-making processes that Cavanaugh recognized as “slow, and quite cumbersome.” In their place today are approaches described as “agile,” a word that has risen to become a cornerstone principle of today’s management methodology.

To plant the seeds of a faster-paced mindset, the company spent the last year running 2,000 of its top managers through new leadership training. That is now trickling down to the rest of BP’s 73,000 employees through role-model programs along with new coding and machine learning courses.

“If you can really unlock how well our engineers, geophysicists, geoscientists, [and] analysts can turn up and participate at work, you can really add value,” Cavanagh said during the Offshore Technology Conference (OTC) in Houston.

He and other BP executives presented an update on how their journey is going so far. The message being shared was emphatic: the company’s embrace of digital technology, and the new workflows that must complement them, have created billions of dollars in savings and new revenue opportunities.

Combining those two elements has been especially impactful on BP’s offshore projects where the company is finding new reserves while driving down cycle times. Earlier this year, BP says it completed the planning and drilling of a deepwater well in the Gulf of Mexico in 13 weeks, half the time of its benchmark. Offshore Trinidad, the company completed a well plan in 4 weeks compared with its usual 4 months—a 75% reduction.

Smaller, incremental gains are adding up too. Improving how it manages its supply chain saved BP about $230,000 over a 3-week period on its Mad Dog platform in the Gulf of Mexico. The company is using digital recreations of its platforms to send fewer people offshore for inspections, a move that saved it $450,000 over a 3-month span last year in Trinidad. “This isn’t about taking shortcuts on process and quality and risk,” stressed Cavanagh. “It’s about how you bring it to teams together to make decisions quicker.”

Spinning Off Startups

Since starting its venture arm a decade ago, BP has put half-a-billion dollars into startup technology developers. Now, the company is creating its own.

Late last year, executives gave the green light to create BP’s first incubator that will take homegrown technologies and spin them off as standalone service firms that can find business with other operators. Its firstborn is called Lytt (pronounced “light”).

Ahmed Hashmi, BP’s chief digital and technology officer, said the incubator program was proposed “because we see value in both venturing in and venturing out.”

While most investments are targeting technologies invented by others, “venturing out” gives BP the chance to see if the wider market can support its innovations and make them flourish. BP has used the technology behind Lytt more than 100 times and says it has generated $100 million in value by detecting unwanted issues such as sand production and leaks in the wellbore.

The service revolves around the interpretation of distributed fiber-optic data, which the industry has been using for more than a decade. Fiber optic cables deliver huge amounts of data from deep below the wellhead, but that can also be their biggest downside.

Operators have struggled to make the most of the 1 terabyte per hour that streams out of these systems, which is equal to watching 1,000 movies online at the same time. Such volumes led BP to create its own solution that boils down to a package of user-friendly apps that parse the information in different ways for engineers.

Tommy Langnes, a fiber optics specialist who has spent almost 7 years working at BP, has been tapped to lead the spinoff. He compared Lytt’s technology with Shazam—a perennially popular smartphone app that uses analytics to take samples of songs playing on the radio and deliver users with the title and artist.

“It’s the same kind of concept where we extract acoustic features from a very rich data set,” said Langes, explaining that to reduce the amount of data that needs to be moved around, the Lytt program looks for only the most important features. Those key signals are picked out and sent to a cloud server where the analytics software fingerprints them and then visualizes what they may mean to engineers.

“There is also an ability to use this fiber as a seismic receiver so we can get enhanced imaging of the well area, which we can compliment with surface seismic,” said Langes. This feature tracks where water is flowing within subsea reservoirs, allowing engineers to change up production plans to improve the sweeping efficiency, possibly delaying a breakthrough.

Lytt is just the first company to exit the new incubator, called BP Launchpad, and there are up to four more internal business lines inside the pipeline.

Digital Dreams Becoming Real

Digital twins—computer models of physical systems—have become a darling of the BP technology portfolio in recent years.

One the biggest projects on this front was launched by the company in 2017. The idea was to build digital twins of production facilities to simulate flow regimes and figure out ways to improve production.

Named APEX, it took BP just a year to scale this program up to 30 of its assets. The company says APEX has taken a systems optimization process that used to require about 24 hours down to 20 minutes. The net result delivered by APEX in 2018 was an additional 19,000 B/D to BP’s baseline production.

In September, BP announced that it had deployed a separate digital twin project to all four of its production platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. Known as the plant operations advisor, the program was developed in partnership with GE’s service subsidary Baker Hughes to monitor thousands of sensors in real time, from any location. Since it was launched, the process-focused analytics platform has been deployed to operations in Oman and Angola.

The company has also instrumented all of its nearly 2,500 wells around the world with sensors that feed data into a cloud-based platform called Argus that is used by engineers to conduct well reviews. Whereas this essential task was once tedious and time-consuming, requiring up to a month to fetch and compile all the required data, Argus visualizes performance metrics and analytics instantly.

Working with a startup called Beyond Limits that it invested $20 million into, BP wants to see if cognitive computing can help manage well activities. The first big test for this “cognitive sandman” is under way in Azerbaijan.

In its North Sea and Trinidad projects, BP has started working with a company in Scotland called Return To Scene that is using technology originally developed for crime scene investigations to create digital recreations of offshore platforms. “Our engineers can actually access this data set and do their pre-planning for turnarounds or maintenance from their offices” said Hashmi.

Inspection Bots Almost Ready

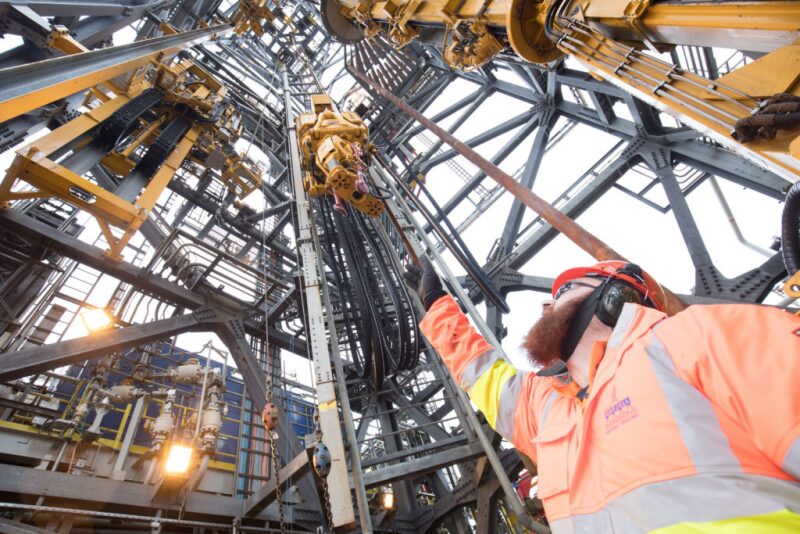

While it has nothing to do with drilling new wells, maintaining the outsides of offshore production platforms is a costly and dangerous task. Companies spend millions of dollars each year on paint to protect from corrosion, however, the job requires workers to be slung over the sides of the platform on ropes. To reduce costs and the exposure to safety risks, BP is turning as quickly as it can to robots.

Designed to live on an offshore oil and gas platform, the first of these inspection bots to be developed was a “crawler” that can climb down the side of an offshore structure using magnetic tracks. Its job is to search for and then measure blemishes or areas of corrosion it comes across. Next in line to be fleshed out is a prototype of a robotic arm on tracks that follows the crawler to grind the steel down and paint back over it.

“When we started out this project in 2017, we expected to cut the cost of inspections in half by 2025. We think we can do much more than that,” said Hashmi, adding that the new robots may enter field service by 2022, and slash those costs by as much as 90%.