Demand for Oil & Gas Will Continue Through the Energy Transition

During this year’s Offshore Technology Conference, multiple panels discussed offshore oil and gas’s role in the nascent transition from higher- to lower-carbon fuels. While this poses opportunities for new technologies and investments, the transition also creates risks for traditional energy producers, including those developing capital-intensive offshore projects. In a lower-carbon world, many existing oil and gas reserves could prove unburnable, meaning that the projects would be “stranded” (Mercure et al. 2021). This is not a trivial challenge as the International Energy Agency (IEA) projected that no new oil and gas fields should be developed if the world were to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 (IEA 2021).

While reaching net-zero carbon emissions in the next 30 years is a laudable and ambitious goal, it is also one that policy makers will likely not reach. Over the last hundred years, global energy demand has risen nearly 10-fold, with fossil fuels representing over 80% of current energy demand. According to the recent bp Energy Outlook, even with recent policy shifts aimed at promoting lower-carbon energy, oil demand is projected to fall by only 20% while natural gas consumption would actually increase (Fig. 1, New Momentum Scenario). Only in more aggressive scenarios where substantial policy changes lead to curtailment of fossil fuels use would oil and gas demand fall by 50% or more (Fig. 1, Accelerated and Net-Zero scenarios). Even then, petroleum could still comprise almost 30% of energy consumed in 2050, leaving room for future offshore oil and gas fields (bp 2022).

Offshore Fields Can Provide Resilient Lower-Carbon Energy

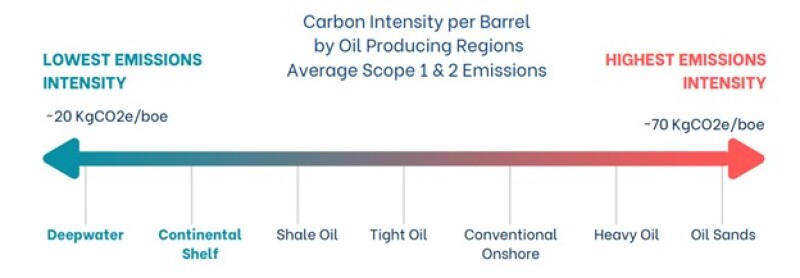

Absent large-scale investments in net-negative technologies like carbon capture, the production, refining, and consumption of petroleum will cause rising greenhouse gas emissions. However, not all sources are the same. Offshore assets have some of the lowest direct emissions of any type of oil and gas production (NOIA).

Beyond that, offshore projects are a better economic fit for a future with declining oil and gas investment. Typically, the bulk of the capital costs are incurred in the first 5–10 years of the project while the field produces over multiple decades (Fig. 3). As the field matures, production typically declines at a moderate pace along with capital spend, limiting the risk of asset stranding. This is distinct from shale where rapid well declines means operators have to maintain significant drilling operations to prevent a substantial drop in production.

Some may argue that in a world with lower oil and gas demand, offshore projects would not be competitive with onshore developments including shale. It is true that producing from offshore oil gas fields, particularly in deep water, has historically required high cost, long-lead projects with substantial geological risks (EIA 2016). However, following the 2014 oil price crash, development costs fell dramatically, making deepwater oil production one of cheapest sources of new supply. Moreover, if countries legislate carbon taxes, or flaring and methane emissions restrictions, onshore costs could rise relative to offshore because plays like the Permian continue to struggle with fugitive methane emissions and routine flaring.

Offshore’s Bright Future

While budget cuts led to less offshore exploration, the industry continues to thrive. Shell’s Vito and bp’s Argos projects in the Gulf of Mexico are expected to start production by year-end, providing 100,000 and 140,000 B/D of new production capacity, respectively. ExxonMobil and its partners continue to make new discoveries in Guyana. The group already has two projects on line and with two more under development and with the recent additional discoveries, the country’s offshore production could exceed one million B/D by the end of the decade, up from zero in 2019. Beyond that, projects continue to advance in Africa and Latin America, contributing to robust production levels. Offshore represents 30% of global production today, and based on current trends, will remain a critical part of the energy landscape in the coming decades.

References

bp Energy Outlook, 2022 Edition. 2022. bp.

Mercure, J.-F., Salas, P., Vercoulen, P. et al. 2021 Reframing Incentives for Climate Policy Action, Nature Energy.

Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector. 2021. International Energy Agency.

Offshore Energy: Fighting Against Climate Change, National Ocean Industries Association (NOIA).

Trends in US Oil and Natural Gas Upstream Costs. 2016. US Energy Information Administration.