The oil and gas exploration and production (E&P) sector has made a U-turn over the past 10 years—changing from an industry dominated by those over 40 into a more youthful one. For the vertically integrated majors, this generational shift in its human resources (HR) has taken place while the companies were managing increasingly technically challenging upstream projects and being answerable to stronger safety and environmental regulation. Few industries have experienced such a profound upheaval.

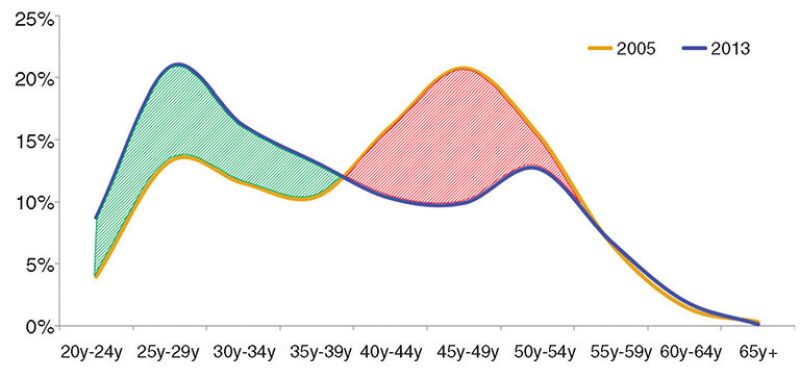

The generational shift in industry personnel is the so-called “big crew change” that is occurring now, as the peer group of engineers hired before the recruitment cuts in the mid-1980s began to retire around 2005. Fig. 1 illustrates the massive outflow of senior petrotechnical professionals (PTPs) from the industry and a corresponding increase in younger, inexperienced graduate recruits.

Since around 2005, the dearth of experience among their human resources has forced E&P companies to rethink the way they manage their talent, putting HR issues at the top of their agenda. Over the past 10 years, companies have focused their efforts on planning manpower needs, reinforcing recruitment capabilities, and fast-tracking skills development, while designing more attractive careers in an effort to better retain their best employees.

Today, the following appear to be the main HR concerns of most oil and gas companies:

- Leadership—Most oil and gas companies remain reluctant to entrust people younger than those hired in the past with similar sets of responsibilities.

- Diversity and Inclusion—There is lower-than-expected growth in areas such as gender and local content.

- Knowledge-Sharing/-Transfer—Not only from senior to junior staff but also between developed and developing countries, this is proving more difficult than expected.

Developing a New Approach to Leadership

Although engineering programs at North American universities are running at capacity, many of the most talented engineers are reluctant to enter the oil and gas industry. This is partly due to the less appealing public image of the E&P industry, when compared to others. Additional reasons include an increasingly widening gap between professional progression within E&P and that of other industries such as high-tech or finance, as well as the harsher lifestyle of some oil and gas careers. For example, a recent oil and gas graduate may be required to live and work in unfavorable remote areas, whereas a graduate entering a tech company may be working at a plush ultramodern campus.

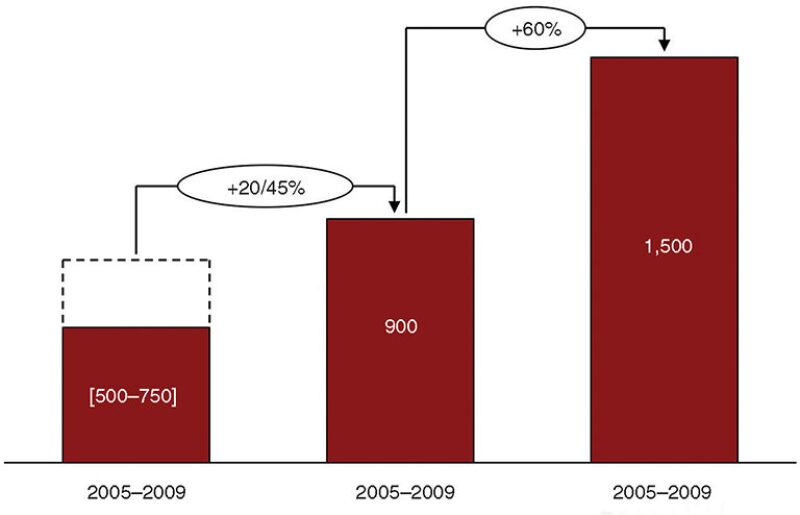

This trend, along with the unsustainable “succession of successions” that accompanies the replacement of top executives—like a series of musical chairs—are pushing the industry to rethink its leadership approach. (Fig. 2 illustrates the industry’s historical and forecast requirements for leadership.) The need for leaders in the next couple of years is greater than it has ever been in this century.

The industry must revise its approach to career development and take more risks with younger people. A few companies have begun succession planning and this wave of change is needed in the middle- and top-management layers: among heads of assets, heads of technical and support functions, and their subordinates. Rejuvenating the population of leaders will create a unique opportunity to increase the attractiveness of the sector.

Critical to the successful identification and development of future leaders is an intimate understanding of the existing talent pool. The most successful companies have developed approaches under which a specific function is managed closely by a dedicated organization. Individual talents are identified and followed, ensuring their suitability to leadership is strongly backed up by a “skillpool” organization.

Diversity and Inclusion Lagging Behind

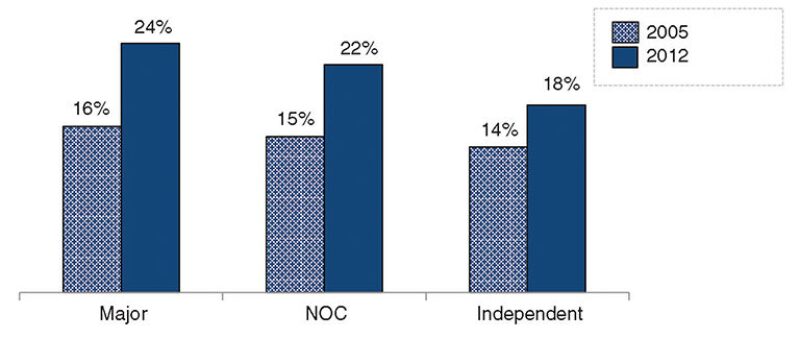

Gender diversity has improved in recent years, but the E&P industry is far from being able to proclaim success in this area, with the number of women seldom exceeding 20% of overall engineering staff. Counterintuitively, it is in the regions and company types where women are usually excluded from positions of responsibility that the most progress is being reported, such as in the Middle East and at national oil companies, whilst international oil companies remain surprisingly conservative in recruiting women (Fig. 3).

A hot topic regarding diversity and inclusion in the industry today is national content or “local content” as it is popularly referred to. After decades of operations in remote locations, the number of locally recruited employees remains far below the desired level. To address this imbalance some resource-rich countries have implemented quotas forcing companies to recruit locally. But despite tangible results, this policy has proved partially counterproductive for several reasons. First, quantitative targets encourage companies to recruit quickly for lower-skilled support func-tions. Second, quotas usually apply to the production phase. In many cases the largest potential for local job creation is during construction when the employers are not E&P operators but engineering, construction, and supply companies.

Third, imposing quotas without investment in national education does not support robust devel-opment of a skilled generation. Too often quotas are used to shift the onus for education from governments to operators. Also, quotas can result in unfair and suboptimal utilization of human resources as not all companies pursue people development policies or contribute to talent pool growth by training young graduates, but rather exclusively poach mid-career talent.

Collaborative Approaches to Knowledge Transfer Are Lacking

The struggle for talent in resource-rich developing countries—where local education systems produce neither the quantity nor quality of required human resources—has been intense during the past decade. Underinvestment in education has many causes, but the main one is lack of appetite among decision makers and operators to invest in long-term benefits. There is also a staggering lack of collaboration among international operators and poor coordination of educational initiatives by local public administrations.

All stakeholders acknowledge that education must come first, but they continue to fight over who will pay: Host governments refuse to integrate education investments by E&P operators into cost recovery; consequently, the companies finance only a few scholarships. The operators themselves do not work together to implement long-term strategies that would bring benefits for all. Several African countries could have hosted international centers of excellence for oil and gas, led and coordinated by a community of IOCs and national bodies. But instead, the focus remains on secondary details, such as which education model should prevail—Anglo-Saxon or continental European.

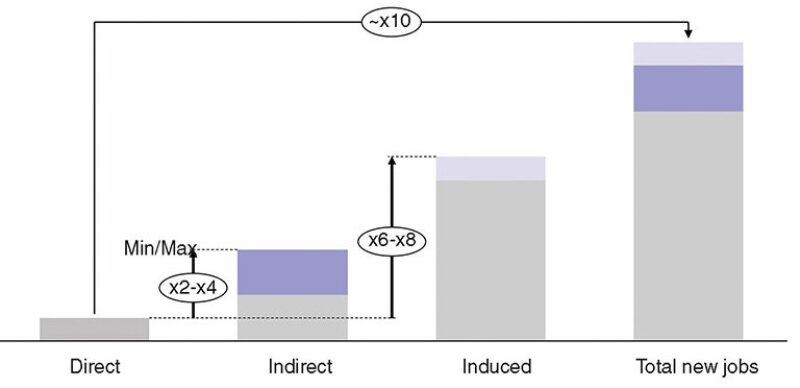

Moreover, investments in education have not targeted disciplines with the largest potential for job creation (Fig. 4). A large E&P project requires top petroleum and geoscience engineers, but far more mechanical or electrical engineers are required. And many more technicians and craftsmen are needed than pure engineers.

Investments in education deriving from oil and gas projects usually address only petroleum disciplines and seldom include technicians. Broadening the scope of education investment to meet the most acute needs could benefit the wealth and long-term development of emerging economies.

Conclusion

Implementing one or more of several strategic initiatives could shape the next decade of the oil and gas industry in a positive way:

- Companies’ boards of directors and CEOs should increasingly focus on discussing ways employees can develop organizational and leadership skill sets.

- The evolution of the HR function from responsive to proactive must continue. CEOs and boards should work as closely with HR as they do with the company’s technical functions or operations.

- Rejuvenation of leadership-development programs: Companies should cultivate a leadership culture to ensure all employees feel genuinely responsible for the domain of their influence, from the immediate areas of interest to societal obligations as well; evolve a high level of com-mitment to performance; and, at the same time, go beyond incremental improvements and search for and implement changes that have the potential to revolutionize the industry.

- Commitment to cultivate a culture of innovation: E&P companies are exploring ways to commit increasing resources to research and development, which, without a culture that breeds imagination, may not unleash their full potential. Nurturing the culture of innovation that can deliver game-changing ideas will require uncompromising dedication from leadership.

- New paradigm of engagement with education infrastructure: companies must learn to work with governments and educational institutions to develop the quality and quantity of skills needed by the oil and gas sector to ensure supply of these critical resources.

If E&P companies commit to some or all of these strategic initiatives, a differently modeled industry could emerge that might enjoy significantly more intellectual ferment and, in turn, could be presented with opportunities that could rejuvenate the industry.

Partha Ghosh is a senior advisor to Schlumberger Business Consulting. Ghosh has more than 35 years of management consulting experience in technology-based and energy industries across the Americas, Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, and the Middle East. He currently focuses on strate-gic, innovation, and leadership issues in the energy industry. From 1977 to 1990, Ghosh was a partner at McKinsey & Company, after which he ran his own boutique advisory firm—Partha S. Ghosh & Associates—focusing on policy and strategic issues. He holds a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from the Indian Institute of Technology, and two advanced engineering and management degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.