An aging workforce and the challenge of locating and exploiting increasingly complex oil and gas fields introduce the theme of this issue: mentoring today’s young professionals. We often hear about “the big crew change” associated with the generation gap in the E&P industry. Mentoring represents the most powerful means to address the problem and facilitate the transfer of knowledge from seasoned seniors to the young. In this issue, we investigate the status of mentoring practices and asked young professionals worldwide to define the qualities of their ideal mentor. —Loris Tealdi and John Donachie, TWA Forum Editors

This survey aims to capture the opinions of our readership on the increasingly important theme of mentoring. Responding to the survey were 569 readers, with 42% from North and South America; 32% from Europe, Russia, and Africa; and 26% from the Middle East, Asia Pacific, and Australia. Of the respondents, 36% were from integrated (major) oil companies, 7% from national oil companies, 28% from service/manufacturing companies, 18% from independents, and 8% were consultants; 63% were from companies with more than 3,000 employees. The median age was in the range of 25–30 years. The male/female mix was 76/24%. More than half of the respondents had more than 5 years of experience in the industry.

The forum was divided into three sections:

- Mentoring practices today.

- The definition of an ideal mentor.

- Mentoring practices tomorrow.

Mentoring Practices Today

Mentoring schemes exist in many guises within large and small organizations across our industry. Some schemes are successful and are recognized as a part of corporate culture. Successful programs are a valuable tool that can increase retention and stimulate overall enthusiasm. Other schemes are fragmented and ill-defined, resulting in poorly managed relationships and demotivated mentors and “mentees.” It is in our industry’s best interest to maximize the effectiveness of mentoring initiatives, and in this issue our questionnaire investigated young professionals’ opinions on the status of mentoring.

A well-structured and clearly defined mentorship initiative has many benefits to employees. Mentoring can create an environment of inclusivity and stimulate retention in an organization. Young professionals can gain great insight into how best to develop and progress within their organization. A strong majority of young professionals recognize that a mentorship program is beneficial (98%) and believe that mentors should be assigned to new employees as part of the company culture (91%). Most young professionals said that having a mentor assigned to them helped improve their skills (93%).

Young professionals can develop their skills and understand their working environment with the help of an engaged and understanding mentor. Two-thirds of respondents indicated that they had one or more mentor, whereas one-third did not have any. It is worth noting that mentoring is a reciprocal process and is not driven only by an organization; if you feel you can learn from someone you know, then you should feel comfortable in approaching them as a mentor.

Communication plays a significant role in a successful mentoring relationship, and your mentor should not be a stranger with whom you rarely communicate; 65% of those who have mentors communicate with them at least weekly. A total of 34% communicated daily, 24% communicated monthly, and 10% communicated less than once a month.

What is your primary focus or area of discussion with your mentor and where do you think that mentoring has the most value?

Mentoring relationships can be diverse: Peers can mentor each other in the interests of mutual development; seniors can assist graduates and new hires in company culture and career progression; technical and professional mentoring can develop a deeper understanding and enhance career prospects. From our survey responses, the primary focus of the discussion was technical advice (55%), followed by development advice (22%) and career advice (13%). Only 1% expressed the need to discuss private life issues.

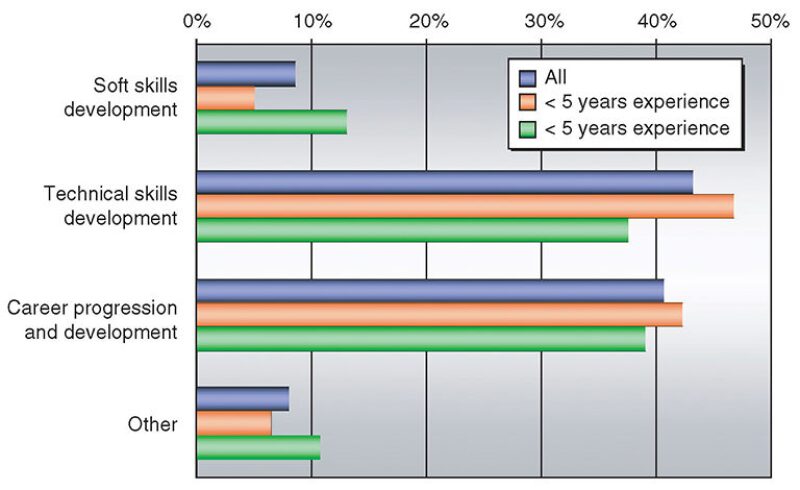

Young professionals believe that technical skills and career development are the areas where mentoring can offer most of the advantage. Those who selected “other” indicated a combination of the preceding choices. Results are depicted in Fig. 1.

What is a mentor?

Young professionals’ perceptions of the definition of a mentor are very telling, and by asking an open-ended question, we were able to explore the level of understanding in our community. Responses show that young professionals clearly understand what a mentor is and can very eloquently describe the role. Below are some representative comments:

- “A mentor is someone who provides guidance and orientation to the new employee(s) in order to put then in the right track technically and in terms of the company's objectives.”

- “A senior peer that takes the challenge to impart knowledge that is generally only learned through experience over a number of years.”

- “Someone to guide you and help you progress based on his/her own experience and his/her knowledge, with mutual trust and respect. Someone you are not afraid to ask questions and you can take criticism from.”

What is the quality that you value most in a mentor?

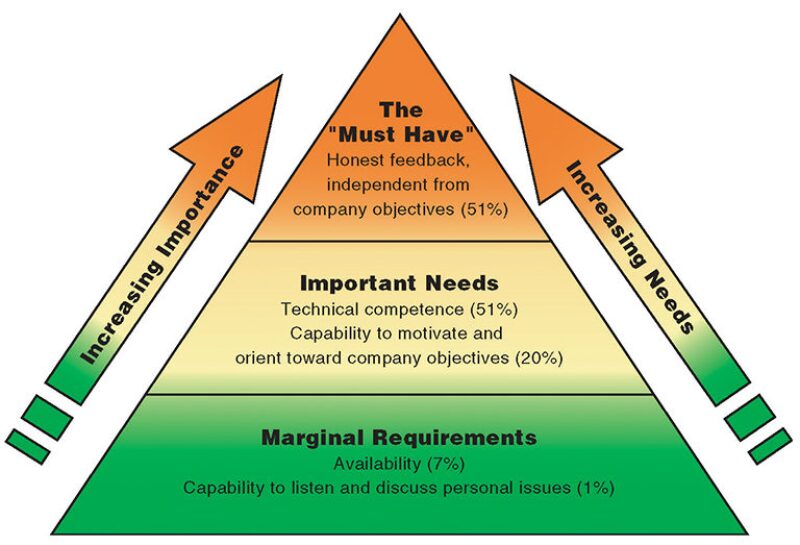

Young professionals require mentors for many reasons and place varying importance on the qualities that they should display. Results are represented in the pyramid box above, which aims to underline these needs and qualities. At the base, we find the marginal qualities, such as availability, which are judged as necessary but not sufficient. Building on this, technical competence and motivation are seen as important needs. Honesty of the feedback, independent from company objectives, is the highest desired quality as selected by the majority of responders.

At which level in the company would you prefer your mentor to be?

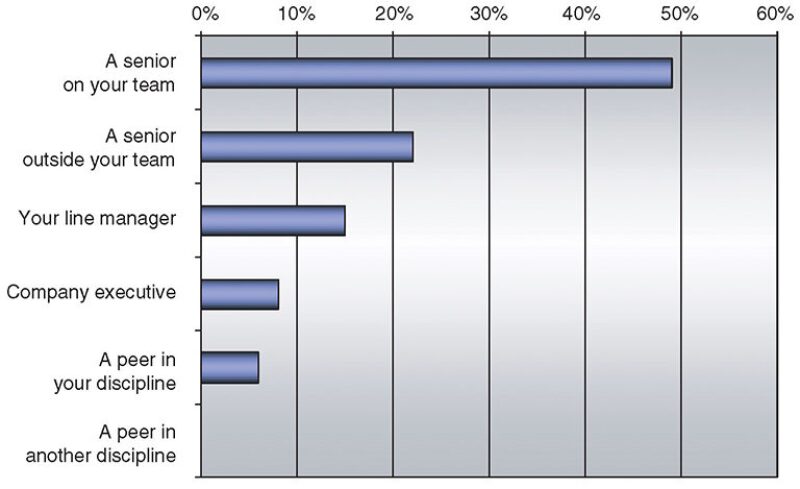

Almost half of the respondents felt that the best person to be a mentor should be a “senior of the team.” A mentor should be independent of the mentee management structure so that they behave objectively. It is interesting to note that only 15% identified their line manager as a mentor. This is in line with the results of Fig. 2, which shows that the most desired quality of a mentor should be “honest feedback, independent from company objectives.” It is clear that the line manager could have some conflict. To compound this, 72% of responses to another question felt that mentors should not be immediate supervisors or in their chain of command. Fig. 3 illustrates the results to this question.

Collecting the most representative comments, a mentor should

- Advise in career development opportunities with honesty, independent from company objectives.

- Help to identify interests/strengths and opportunities and try to align them.

- Help to identify area for improvement.

- Have and demonstrate seniority and technical experience to drive young professionals, especially at the beginning of their career.

- Have strong soft skills and, in particular, excellent listening skills.

- Be able to manage people and relationships.

- Effectively manage expectations.

- Offer advice on how best to manage challenges at work.

- Be a senior of the working team but not a direct supervisor.

Does your company offer mentoring to employees?

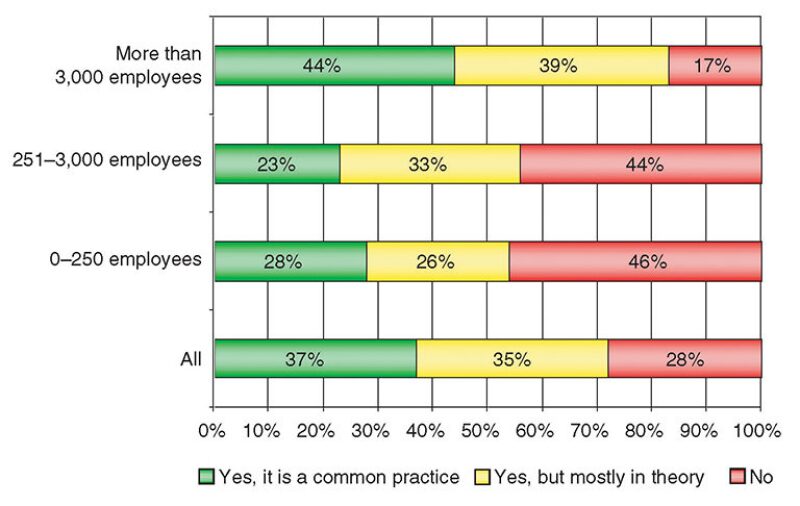

Only 37% said that mentoring was a common practice in their company, while 36% said that mentoring to employees was offered, but mostly in theory; 27% said that mentoring was not offered. Fig. 4 shows the different attitudes of the companies based on their size: The larger the company, the more the mentoring practices are diffused.

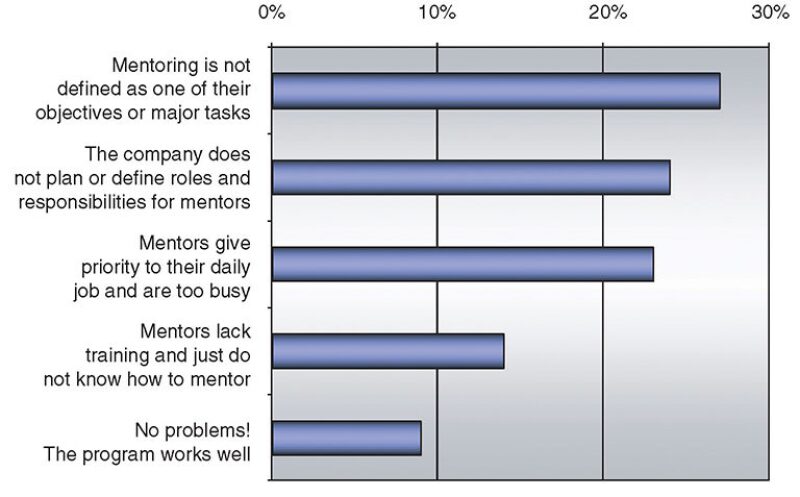

What problems have you identified with the way mentoring is performed in your company?

Only 9% said mentoring practices are conducted “very well” in their company, while 47% said “somewhat well”; 30% felt that they were conducted poorly. Fig. 5 indicates the critical reason behind unsuccessful mentoring programs. The problems respondents identified are mainly related to whether or not mentoring is considered as “an official and recognized task.” Mentoring is often unsuccessful when a mentoring relationship is not defined and assigned mentors are not evaluated or rewarded for their effort. Mentoring is often seen as an additional task that seniors offer in parallel to their main role and not integral to their role.

To understand the needs to develop mentoring for tomorrow, a few questions probed the weaknesses of existing practices, and from this we identify opportunities for improvement.

How do companies transfer knowledge from senior to junior staff? Can mentoring be the means to overcome the possible lack of know-how in the coming years?

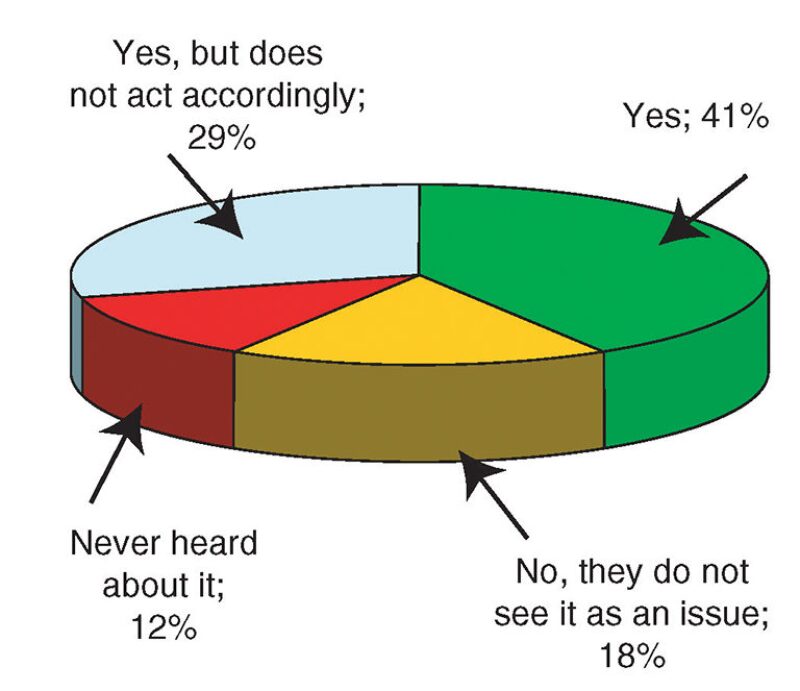

Forty-one percent of the respondents felt that their company viewed a “big crew change” as a problem, while 29% said their company saw it as a problem but failed to act accordingly; 18% felt that their company did not see it as an issue. Only 12% of young professionals are not aware of the ongoing and upcoming “crew change” (Fig. 6a).

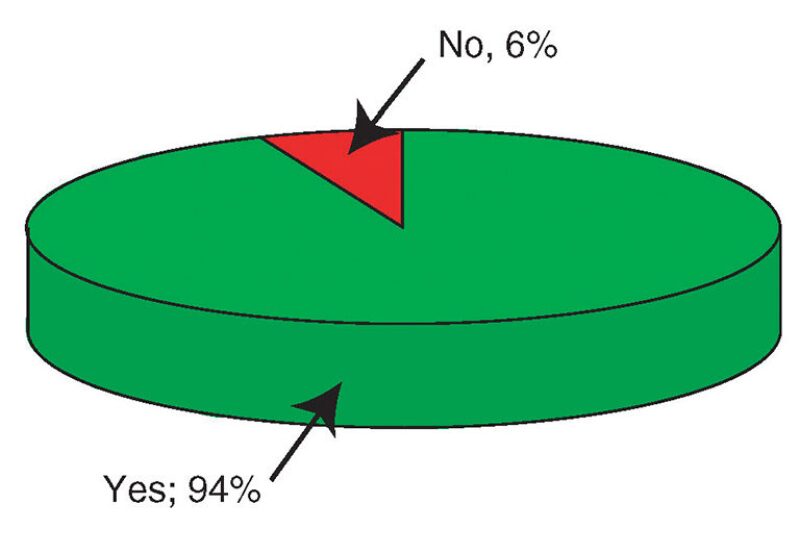

The majority of respondents identified a well-planned mentoring program as the solution (Fig. 6b).

Conclusion

Our results clearly indicate that young professionals assign a great value to mentoring. They crave advice to improve their technical skills and assist in their career progression and professional development. The results made it possible to identify the characteristics of an ideal mentor. They need to be completely honest and give objective advice independent from the management chain of command. Consequently, young professionals prefer to be mentored by experienced seniors of their team instead of line managers. The survey identified possible opportunities for improvement, mainly associated with defining mentoring practice: making mentoring part of the company culture with time made available for it; mentor/mentee roles and relationships should be clearly defined so both parties understand the parts they play; and mentors should be evaluated and rewarded on the basis of their mentoring attitudes.

Young professionals believe that mentoring is the main solution to the “big crew change,” enabling the transfer of knowledge from seasoned seniors to motivated and ready-to-learn young professionals. Our industry needs to address gaps in current mentoring practice to ensure that valuable knowledge is transferred before it leaves us.

Do you want to know more about this topic or comment on this article? Visit the Young Professionals Network at www.spe.org.