Prior to the outbreak of the global pandemic, the oilfield supplier space was ripe for consolidation. Now, massive sector consolidation seems all but inevitable.

Some acquirers (buyers) will pick up companies on the verge of insolvency. Others will find those coming out of bankruptcy more attractive. Mergers of equals will also occur.

There is a host of reasons companies have historically pursued mergers: underachieving businesses or CEOs seeking a change in luck, the elimination of nettlesome rivals, copycat mergers pushed by fee-hungry investment bankers, and others. Some deals are premised on cost synergies, some on revenue synergies. Still others hope to improve financial strength.

People, Flow Charts, and Egos

The coming merger-and-acquisition (M&A) wave in the oil and gas supplier sector will be spurred mostly by the need to reduce chronic overcapacity. On the surface, this is good news. Unfortunately, there’s a wealth of evidence that suggests even necessary corporate combinations can end up destroying wealth. The mistreatment of customers is one reason.

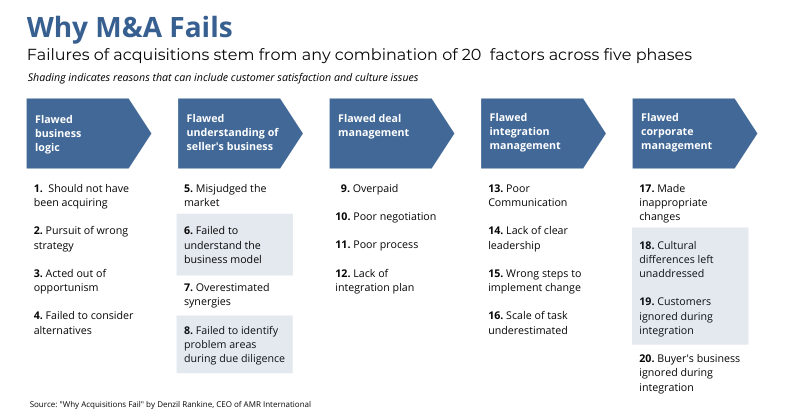

One particularly in-depth study of the effects of M&A was published by Denzil Rankine, executive chairman of consulting firm AMR International. In his book Why Acquisitions Fail, Rankine identifies 20 reasons acquisitions fall short of expectations. At least four relate to customers.

Management guru Peter Drucker famously noted, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” Dutch consultant Martin Roll concurs, pointing out that humans aren’t as straightforward as flowcharts. People have emotions, habits, expectations, needs, and opinions. If the cultures of two organizations are not good fits, chances are a strategy to combine them won’t work.

One reason customers are taken for granted during mergers is corporate ego. That is, buyers typically do not view their targets (sellers) as being as well managed as themselves. Nor do they typically believe sellers have better products or services, more talented employees, or better client relationships.

Even when buyers acknowledge a seller’s strengths, they rarely appreciate the factors that underpin them. And almost by definition, they believe they can do as much or more with a seller’s assets—even as they plan cost cuts and headcount reductions.

With this overconfidence as the backdrop, when the integration phase of a merger begins, customers are often assured their needs are front and center—and that good things are in store.

Inured by experience, many customers are skeptical of the promises. And when performance falls short—or no unifying culture emerges, as is often the case—the skepticism turns to dissatisfaction. If quality and service decline enough, customers leave. The downward spiral continues when competitors swoop.

Combination Types

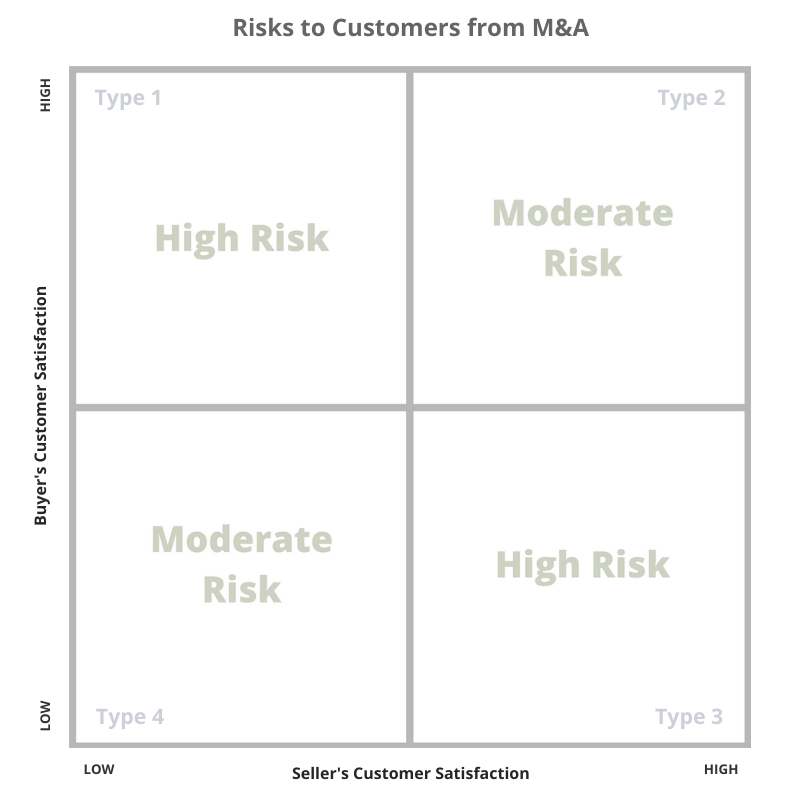

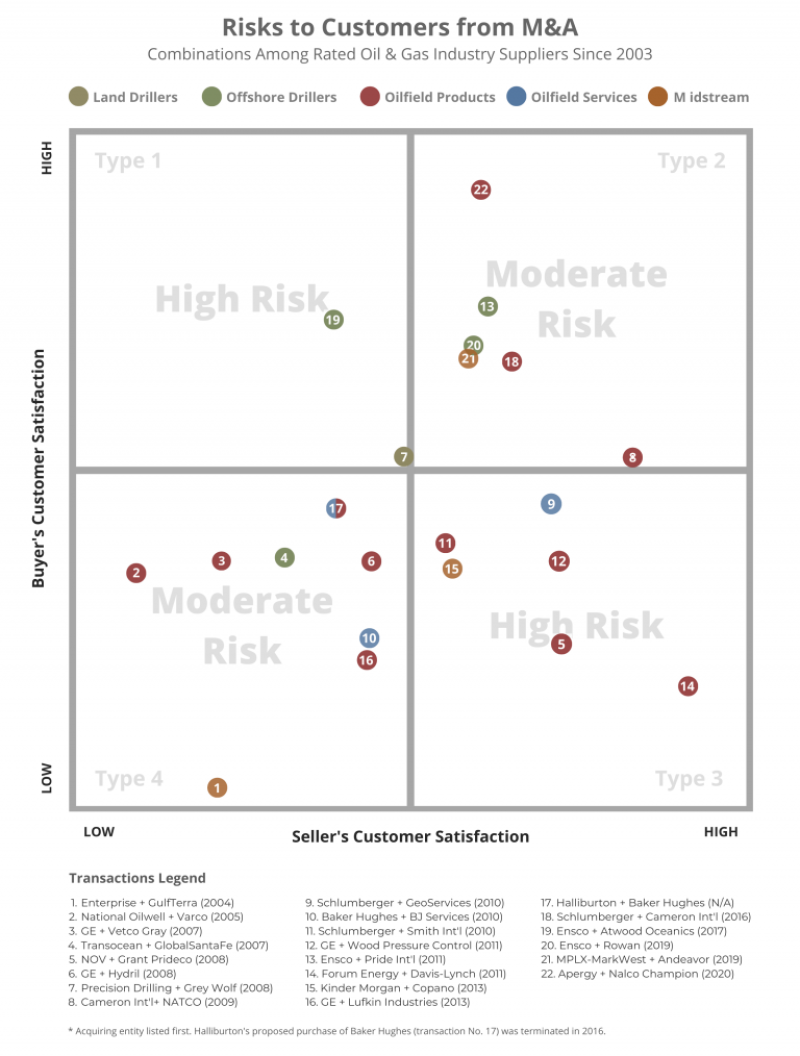

While most M&A tends to hurt customers, in rare occasions it can help. EnergyPoint Research has developed a framework for understanding when this might be the case. What's more, by plotting past transactions in the framework, we can estimate the prevalence of various types of transactions within the sector and their impact on stakeholders.

The framework is a simple matrix. The X-axis is the seller’s customer satisfaction rating in EnergyPoint’s independent surveys; the Y-axis is the buyer’s rating. The midpoint of each axis is the industry average. Every transaction falls into one of four quadrants, each with certain risks and risk levels for customers.

TYPE 1: High Satisfaction Buys Low Satisfaction. Logic suggests highly rated buyers can improve the practices, offerings, and personnel of lower-rated sellers. Hence, type-1 mergers theoretically offer opportunity.

In reality, such deals are rare. The fear that a lower-rated seller will hurt the performance and reputation of a buyer is likely a major reason. The time and resources needed to remedy cultural issues is another.

Of the 22 oilfield transactions since 2003 for which EnergyPoint has data, only Ensco’s purchase of Atwood Oceanics in 2017 falls squarely in this high-risk quadrant.

TYPE 2: High Satisfaction Buys High Satisfaction. Highly rated companies tend to respect each other’s cultures. As a result, type-2 combinations are typically lower risk for customers.

Since 2003, about one-quarter of mergers between oilfield suppliers are judged to be type-2 transactions. Apergy’s acquisition of Nalco Champion in 2020 is a recent example.

Type-2 deals are the only transaction type associated with higher post-deal customer satisfaction, although only modestly so. Shareholder returns are more impressive. Average 2-year stock-price returns for these combinations exceed the industry average by 16.2 percentage points.

No transaction type is foolproof, however. Integration efforts can bring disorder—even for type-2 deals. Cultural issues can be especially time-consuming. Best case, the process goes well and customers continue to enjoy high levels of quality and service. When the process doesn’t go well, however, key employees and managers can leave, hurting performance and continuity.

On balance, type-2 combinations represent moderate risk for customers.

TYPE 3: Low Satisfaction Buys High Satisfaction. It may seem that companies with low customer satisfaction seldom acquire those with high satisfaction. In reality, more than a quarter of the transactions in EnergyPoint’s database are of this type.

Often, buyers are larger players seeking to add share in existing or new markets, or to fend off or eliminate competition. Schlumberger’s purchase of Smith International in 2010 is an example.

Type-3 combinations are disruptive and they risk damaging the performance and reputation of the seller and its brands. Since such deals often come with hefty premiums, cuts can run deep. In addition, buyers tend to impose their own cultures more quickly and unreservedly, sometimes hastily pushing long-time employees and customers out the door.

While investors have enjoyed modest 24-month excess returns of +3.0 percentage points, type-3 deals pose a high risk to customers, with a post-transaction median decline in customer satisfaction of 19.9%.

TYPE 4: Low Satisfaction Buys Low Satisfaction. Two companies that are unwilling or unable to look after their own customers rarely solve the problem by joining forces. Since both lack strong customer cultures, the focus for type-4 deals is often cost reductions and increased market power. Both typically lead to greater customer dissatisfaction.

Even so, type-4 mergers carry only moderate risk for customers, who are already accustomed to below-average performance from the two suppliers. Historically, satisfaction ratings in these transactions decline 1% within 24 months, while investor returns underperform by 2.6 percentage points.

These underwhelming results don’t discourage such deals, however. In fact, more than one-third of the transactions in our database are type 4. These include the merger between National Oilwell and Varco in 2005, as well as Transocean’s ill-fated acquisition of GlobalSantaFe in 2007.

Five Smart Steps for Buyers

On the whole, there’s little evidence that M&A among oilfield suppliers benefits investors. There’s plenty of evidence, however, to suggest it hurts customers on average. At best, type-2 deals reward shareholders while not harming customers. The remaining deal types are linked to both lower customer satisfaction and lower investor returns—odds and outcomes hardly worth pursuing in normal times.

Even so, deals will happen. And when two companies and cultures come together, change is often required—certainly with the seller, but often with the buyer as well. Caught in the middle are customers, who rarely feel like winners.

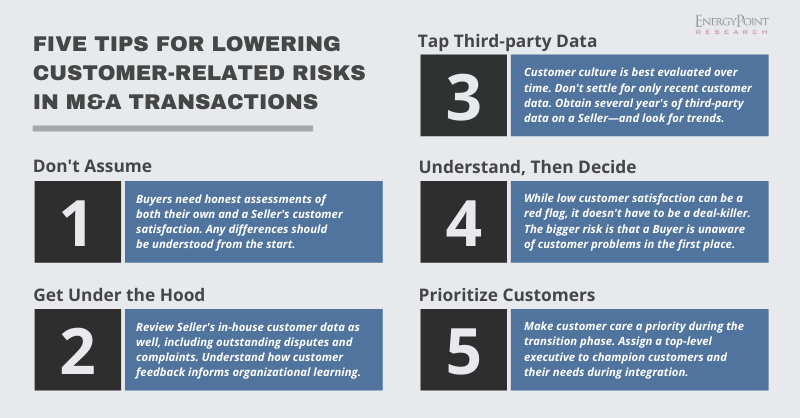

The good news is that there are steps buyers can take to minimize risks to customers and performance in the coming M&A wave. Here are five tips all companies should keep in mind:

Tip 1: Buyers shouldn't assume their own customer satisfaction is higher than that of a seller. It may not be. Market-share data is important for due diligence, but it’s not an all-encompassing metric. Buyers also need honest assessments of customer satisfaction and culture. Since a seller’s satisfaction level and culture may diverge markedly from a buyer’s, any differences need to be understood, as well as planned and accounted for, prior to inking a deal.

Tip 2: Delve into in-house customer-satisfaction data. Buyers should carefully examine a seller’s in-house customer service, satisfaction, and quality records going back at least 3 years. Review the data by product or service line, region, function, etc. Plot the data over time to discern trends. Also determine how customer feedback informs organizational learning.

Whether a seller can provide this data in an organized and prompt manner can be an important indication of its customer culture. Treat with skepticism thin data or assurances that the seller hasn’t had the need to track customer satisfaction or feedback.

Tip 3: Utilize reputable customer data from independent third parties. Wider lenses provide more complete pictures. Hence, third-party customer data on a seller and its rivals can be immensely valuable. If a buyer also has comparable data on itself, preferably from the same third party, all the better.

As with in-house customer information, the point with third-party data is to understand current satisfaction levels and trends. EnergyPoint’s database contains tens of thousands of independently collected customer evaluations on a large number of companies going back several years. Other parties may have archival data as well.

Tip 4: Treat customer satisfaction as a barometer, not as a litmus test. Low customer satisfaction at a seller isn’t necessarily the primary risk; missing or ignoring the causes is. If problems go undetected in due diligence, or unaddressed in integration, trouble typically follows.

With solid due diligence and thoughtful integration, buyers can potentially create value by enhancing the customer satisfaction and culture of the seller. It’s not easy, but it can be done.

Tip 5: Assign a customer champion. If and when a deal is struck, place customer care front and center from the beginning.

As Dan Kiely in the Harvard Business Review suggests, task a senior-level executive, possibly the COO, with protecting customers’ interests during decision-making and execution phases. Whatever the plan, its frequent and clear communication matters to customers.

Conclusion

There’s no getting around the fact that M&A can be a threat to stakeholders, including customers. Regardless of a deal’s form, having the right attitude, data, and plan regarding customers improves the odds of success. It can provide the insight to walk away when a seller is not a good fit, or the confidence to move forward when the opportunity is right.

The article was sourced from the author by TWA editor Stephen Forrester.