Editor's Note: Abdulmalik Ajibade is a member of the TWA Editorial Board and a contributing author of previous TWA articles.

Designing reliable agentic artificial intelligence (AI) systems for technical workflows demands reconciling two fundamentally different paradigms. On one side are language models: stateless, probabilistic, and conversational by nature. On the other are engineering workflows: stateful, deterministic, physics-constrained, and computationally precise. Bridging these worlds is not automatic.

A large language model (LLM) that can accurately explain petrophysical equations does not inherently manage session state, respect calculation dependencies, or distinguish between internal computation and user-facing interpretation. These capabilities must be deliberately engineered into the system's architecture.

Over several months of developing an agentic well log interpreter, recurring challenges surfaced at the boundary between autonomous reasoning and physics-driven computation. Although the work focused on petrophysical interpretations, the issues were not domain-specific; they arise whenever agentic systems interact with deterministic, stateful technical workflows.

From this experience, five critical design lessons emerged. Each exposes a failure mode encountered during development, explains its root cause, and outlines the architectural adjustments required to overcome it.

This article offers practical guidance for designing AI agents that must operate within physics‑bound, deterministic workflows.

Lesson 1: Prompts Are Not Control Systems

A common assumption in early agentic system design is that carefully written system prompts can reliably govern agent behavior. During development of the well log interpreter, significant effort was initially invested in refining system prompts to encourage efficient execution, prevent redundant calculations, and guide the agent through the intended workflow.

In practice, this approach proved insufficient. Small changes in prompt wording produced disproportionately large changes in agent behavior, including extended runtimes, repeated execution of completed steps, and unbounded multistep reasoning. In several cases, the agent continued performing calculations after the intended workflow had already been completed, despite explicit instructions to stop or summarize results (Fig 1).

This behavior reflects a fundamental limitation of language models. Prompts influence what the model attempts to do, but they do not provide enforcement mechanisms. Language models do not possess intrinsic awareness of system state, completed tasks, or computational cost. Therefore, control must live in deterministic code, not in natural-language instructions.

Without explicit architectural constraints, an agent will continue generating actions as long as the prompt and tool design permit autonomous reasoning.

In engineering workflows, this lack of enforcement is unacceptable. Petrophysical interpretation requires strict control over execution order, data reuse, and termination conditions. Re-running calculations unnecessarily not only increases computational cost but also introduces opportunities for inconsistency and error.

The solution was to shift control responsibility from the system prompt into the architecture itself. Workflow boundaries, state checks, and termination conditions were implemented directly in code. The agent was allowed to recommend actions, but execution was gated by deterministic logic that verified whether required inputs existed, whether calculations had already been performed, and whether the workflow had reached a valid stopping point (Fig. 2).

With these controls in place, the system became both more predictable and more efficient. The system prompt remained important for high-level guidance and interpretation style, but correctness, efficiency, and termination were enforced through explicit architectural design rather than linguistic instruction.

Lesson 2: State Is Not Implicit, It Must Be Engineered

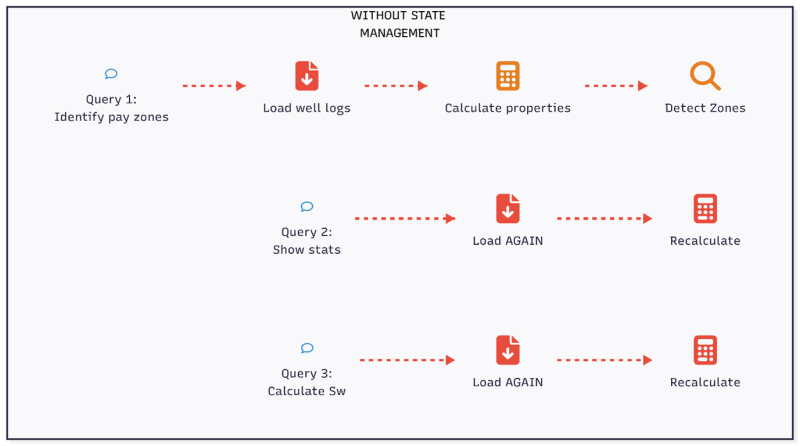

Language models are stateless by design. Each request is processed independently, with no inherent memory of previous calculations. For technical workflows involving multistep computations, this creates a fundamental problem: the agent cannot distinguish between work already completed and work that still needs doing.

During development, this manifested as systematic inefficiency. The agent would load the same Log ASCII Standard (LAS) file multiple times within a single session, recalculate properties that already existed, and repeat quality checks on data validated minutes earlier. A user requesting "average volume of shale (Vsh) values" would trigger a complete reload and recalculation despite Vsh having been computed thirty seconds prior for identifying pay zones (Fig 3).

The solution was to make state explicit and enforceable. Before any data load or calculation, the system now performs deterministic checks to confirm whether the required data already exist in memory or within the working dataset. Calculations are only executed when their prerequisites are satisfied and their outputs are absent. Once completed, results are stored and reused rather than recomputed (Fig. 4).

By externalizing state management from the language model and enforcing it through code, the system transitioned from reactive behavior to controlled execution. The agent retained flexibility in interpretation and reasoning, while the workflow itself became predictable, efficient, and auditable.

Lesson 3: Physics Dictates Order

Petrophysical interpretations have strict dependencies. Water saturation requires porosity. Porosity benefits from shale correction, which requires shale volume. Pay zone identification requires all three properties. These dependencies are not arbitrary preferences; they are requirements imposed by the underlying physics.

Language models do not inherently recognize such constraints. When asked to "calculate water saturation," an agent may attempt the calculation immediately, without verifying that required inputs exist. If porosity has not been calculated, the water saturation equation receives undefined values, produces Not a Number (NaN) results, and the agent reports success unaware that the output is meaningless (Fig 5).

In physics-driven domains, such flexibility is dangerous. Execution order encodes assumptions about rock properties, fluid distribution, and measurement correction. Allowing an agent to violate these dependencies undermines the integrity of the entire interpretation, even when individual calculations appear reasonable in isolation.

The resolution was to formalize execution order as a first-class architectural constraint. Each calculation was assigned explicit prerequisites, and the system was prevented from executing a step unless all required inputs were present and validated. Once a calculation completed successfully, its outputs were locked and made available to downstream steps, ensuring that subsequent computations were based on fully resolved inputs.

Lesson 4: Separate Calculation From Communication

Tools should return data, not prose. This distinction becomes critical when building user-facing agentic systems where internal computations must be clearly separated from external communication.

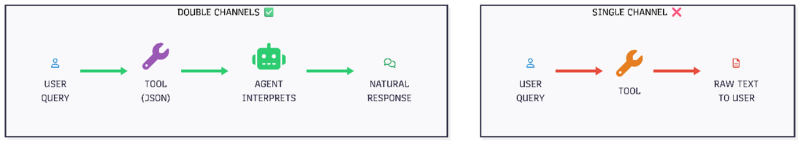

During development, tools were initially designed to return formatted text, quality reports with headers, statistical summaries with labels, and calculation results with explanatory messages. This seemed user-friendly but created a fundamental problem: the system had no separation between internal tool execution and user-facing interpretation.

The result: users saw raw tool outputs instead of synthesized insights. Interfaces displayed debug logs, execution confirmations, and technical details that should have remained internal. A simple query like "What's the average Gamma Ray (GR) value?" produced responses that looked like system logs rather than conversational answers.

The resolution involved enforcing a strict separation of concerns. Tools were redesigned to return structured outputs rather than textual messages. Internal diagnostics were retained for debugging but suppressed from user-facing channels. The agent was required to synthesize final responses explicitly, transforming structured tool outputs into concise, interpretable summaries suitable for engineering review (Fig 6).

Lesson 5: Autonomy Requires Justification

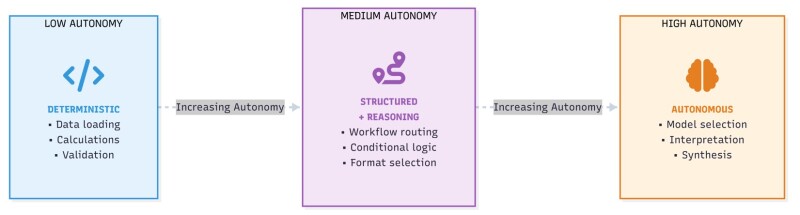

A common misconception in agentic AI is that systems must be either fully autonomous or purely procedural. In practice, effective subsurface interpretation systems operate along a spectrum of autonomy, where decision authority is distributed across different stages of the workflow.

In well log interpretation, certain tasks are well suited for autonomous execution. Log conditioning, deterministic petrophysical calculations, cutoff application, and repetitive report generation follow established rules and benefit from consistent execution. Granting autonomy at these stages improves efficiency without introducing interpretational risk.

Other tasks require structured decision-making rather than free-form reasoning. Pay zone identification, flagging ambiguous intervals, or selecting interpretation models are better handled through agentic workflows where the agent proposes actions or interpretations but operates within predefined constraints and validation checks.

Full autonomy where an agent independently decides what logs to use, which equations to apply, and how to revise interpretations proved unreliable. Such freedom often led to inconsistent assumptions, circular reasoning, or violations of petrophysical principles.

The most robust architecture emerged from combining deterministic pipelines with agent-driven orchestration. In this hybrid approach, autonomy is granted only where the task is repeatable, auditable, and physics-bounded, while higher-level interpretation remains guided by explicit workflow logic and engineer oversight (Fig. 7).

Conclusion

Agentic AI can add real value to subsurface workflows but only when it is engineered to respect the constraints of physics, data, and decision accountability. The experience of building an agentic well log interpreter demonstrates that reliability does not emerge from increasingly powerful language models, but from architectures that deliberately separate reasoning, computation, interpretation, and validation.

The future of agentic AI in subsurface will not be defined by how autonomous agents become but by how precisely autonomy is designed.