The secret of success is to do the common things uncommonly well.

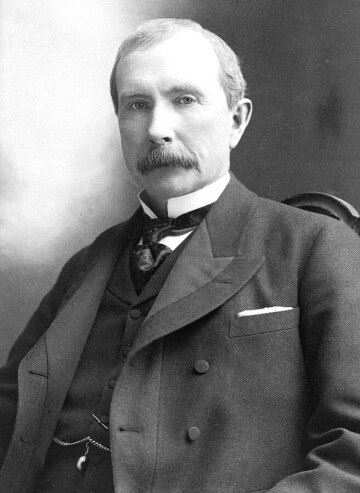

American businessman and founder of Standard Oil Company, John D. Rockefeller, holds the distinction of being one of the richest individuals in American business and economic history. His estimated net worth of $1.4 billion at the time of his passing in 1937 would be worth more than $21 billion in 2024.

It would seem obvious that a man of his means was strong, versatile, and clever. He improved the oil market by building an efficient infrastructure network more than 150 years ago, when reliable transportation from one side of the US to the other could not be taken for granted.

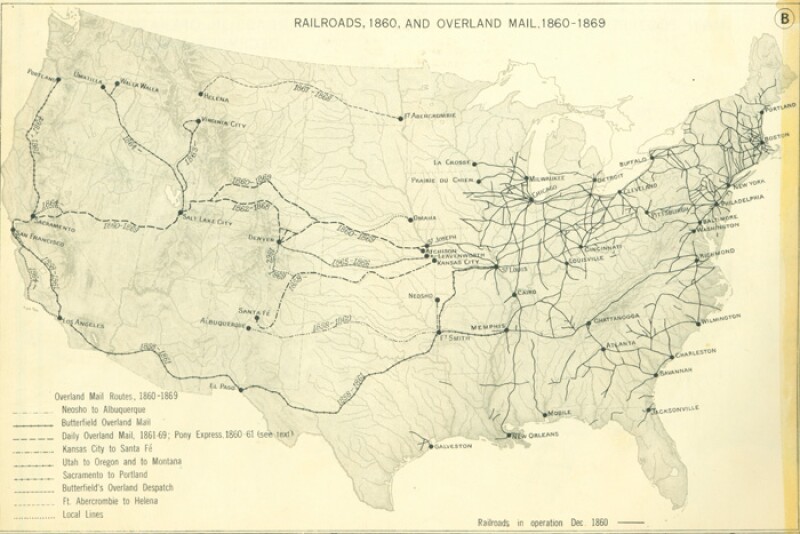

At that time, both the oil industry and its transport infrastructure were not fully developed. In the 1880s there were very few railroads which connected major industrial focal points in the eastern US and even fewer in the western US. The oil industry at the time was focused on kerosene and suffered from the lack of an infrastructure apparatus.

Early Life and the Standard Oil Company

Rockefeller’s career started as an accountant for a small agricultural produce firm in Cleveland, Hewitt & Tuttle. In this role, his tasks were to inspect and analyze company financial accounts. When he was 19, he founded his first commission business, Clark and Rockefeller, with business partner Maurice Clark. They were involved in the wholesale of agricultural products (mainly grain, meat, and other goods). Rockefeller was the financial manager, while Clark ran the operations (Chernow, 1998).

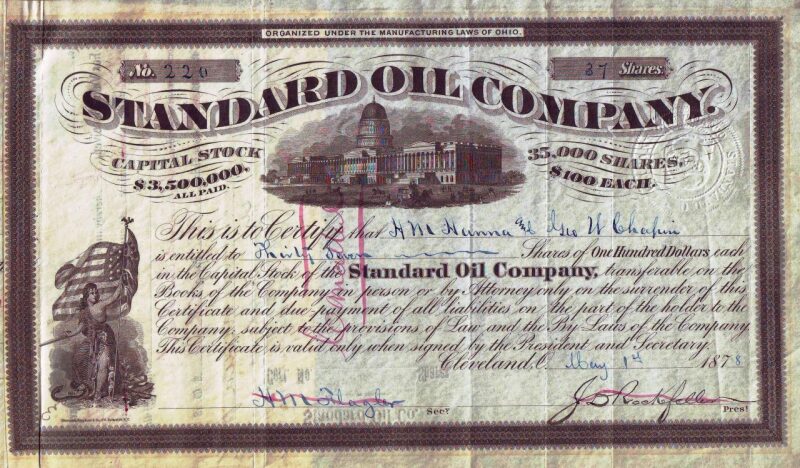

Home to 26 refineries, Cleveland was one of the focal points of the petroleum refining industry at the time. Sniffing oil patch earning potential, Rockefeller decided to invest in buying his first small refinery in Cleveland in 1863. In 1870, he founded Standard Oil, and with the help of agreements with railway men, his business experienced near-sudden expansion and growing popularity. Within 10 years, he succeeded in buying 22 of 26 refineries in Cleveland, playing hardball during negotiations. If his competitors failed to accept his first acquisition proposal, he threatened to run them into bankruptcy and acquire them at the consequent auction.

This ruthless strategy, combined with the growing energy demand of the US, led to him owning and managing the entire US oil production and refining market.

The Importance of Railways

Between 1860 and 1880, the railway sector saw exponential growth, thanks to a number of factors. First, the energy market in the 1880s was led by coal, which remained the primary fuel and source of power for railways until the 1940s. The US was the world's most important coal producer (US Department of Commerce, 1957), so goods and transportation had low prices. Secondly, the importance of railways in freight transport saw fast growth. In 1860, state-owned and non-state-owned railway companies managed more than 15,000 km of railway lines. Between the 1860s and 1880s, this sector saw another strong growth, thanks to the emerging oil market. Thirdly, the vastness of US land and the low population density helped the railway sector move toward freight transportation rather than passenger services.

Cleveland was in the middle of the densest railroad network (Fig. 1), well-connected to the Atlantic Coast. Over the next 20 years, the number of new connections exponentially increased.

Rockefeller perceived an opportunity to utilize the railway network for the oil industry, obtaining a discount for the transportation of oil barrels in exchange for guaranteeing a minimum number of barrels (Rockefeller, 1909). Oil transportation and the easy movement of semi-finished and finished products were fundamental for business growth. The Cleveland model was soon exported to the other Standard Oil refineries. The large-scale distribution granted by railways played a fundamental role in a world that had not seen automobiles yet.

Large-Scale Economy

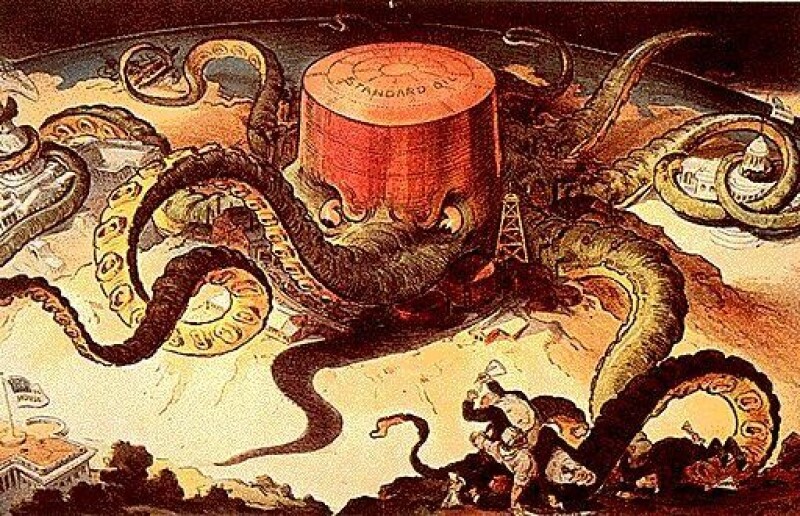

Rockefeller was one of the first people in the oil industry to implement a vertically integrated business model strategy in such a large-scale company, joining exploration, production, and refining. In doing so, he managed the costs of each phase, offering products at lower prices and pushing out competitors. Furthermore, Rockefeller not only bought out his competitors, but also infrastructure such as pipelines, tankers, and distribution warehouses.

Upstream, midstream, and downstream were joined together in a unique supply chain. The exponential growth met by Standard Oil was driven by a modern and successful economic system, capable of meeting and adapting to growing market demand for oil-derived products. At the end of the century, the birth and the introduction of the internal combustion engine and the subsequent rapid development of the automobile market increased demand for refined products such as gasoline and diesel.

This vertical integration allowed Standard Oil to optimize costs and to drive oil refining to fuel, outclassing competitors.

Trust and Antitrust

By 1882, Standard Oil controlled nearly all of the US oil market (Fig. 2). However, the control of such a multinational company was not easy due to differential laws within their countries of operation.

For this reason, he first divided the company into 20 smaller satellite companies, each operating in one or two states. The controlling company became the Standard Oil Trust, which made things simpler to manage and lowered prices, making it more difficult for other companies to compete.

In 1890, the Sherman Act was approved by the US government, thanks to the effort of the congressman John Sherman. The first real application of the Sherman Act was in May 1911, when the US government ordered the division of the Standard Oil Trust into 34 new companies (Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States). With Rockefeller owning nearly 30% of their shares, the division of the trust resulted in a significant financial gain for him. Following the breakup, several new companies emerged from the remnants of Standard Oil, with some of the most well-known including

- Standard Oil of New Jersey (SONJ), subsequently renamed Exxon and, from 1999, part of ExxonMobil.

- Standard Oil of New York (Socony), subsequently renamed Mobil and, from 1999, part of ExxonMobil.

- Standard Oil of California (Socal), renamed Chevron, later merged with Texaco in 2001 to become ChevronTexaco and now back to being known as Chevron.

- Standard Oil of Indiana (Stanolind), renamed Amoco, now part of British Petroleum (BP).

- Standard’s Atlantic (Atlantic Oil), before part of Arco, now part of BP.

- Standard Oil of Kentucky (Kyso), today part of Chevron.

- Continental Oil Company (Conoco), today, ConocoPhillips.

- Standard Oil of Ohio (Sohio) which is today part of BP.

The importance of the companies born from the Standard Oil division is highlighted by the fact that three of them (Exxon, Mobil, Socal) were included in the Seven Sisters, (a term used by Eni founder Enrico Mattei (Sampson, 2009) to describe the seven companies that controlled global oil market between 1940 and 1973). Their role and their weight in the global oil market lasted until the nationalization of Middle Eastern oil production and the foundation of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

Rockefeller’s Legacy

In 1913, Rockefeller established the Rockefeller Foundation to provide funding for universities and research centers in various fields including health, arts, technology, and agriculture. During his later years, he dedicated himself to improving his public image, which had been criticized for many years.

The Rockefeller Foundation is now at the forefront of global improvement and has founded international health projects (e.g., vaccine production and distribution, virus eradication, medical staff training), technology (e.g., Rockefeller University Foundation, penicillin discovery), green evolution in agriculture, and sustainable energy. The foundation is distinguished for its innovative approach to philanthropy, focusing on long-term and systemic issues.

For Further Reading

The Antitrust Legacy of Standard Oil in Today's World by J. Blaney, TWA

Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, by R. Chernow (1998).

Historical Statistics of the United States, 1957, US Department of Commerce.

Random Reminiscences of Men and Events, by John D. Rockefeller, 1909.

John D. Rockefeller, Heidi Fearing (2023), Cleveland History

Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, 221 U.S. 1 (1911)

The Seven Sisters: The Great Oil Companies and the World They Shaped, by A. Sampson (2009).

Member Countries, OPEC website.

To Cast Out Disease. A History of the International Health Division of Rockefeller Foundation (1913-1951), by John Farley, 2003.

New York State Oil, Gas and Mineral Reserves, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (2002), Division of Mineral Resources.