Editor's Note: Piergiuseppe Fiore is a member of the TWA Editorial Board and a contributing author of previous TWA articles.

Venezuela is one of the most complex and educational cases for the world energy scenario. The country combines absolute primacy in terms of oil reserves with one of the deepest shrinkages ever recorded in production for one of the main OPEC producers.

To properly understand the evolution of the Venezuelan energy framework, it is necessary to analyze the interaction between geology, technologies, industrial governance, international sanctions, and market dynamics.

Geological Characteristics and Crude Oil Properties

Venezuela’s subsurface holds more than 300 billion bbl of proven oil reserves with 80% concentrated in the Orinoco Belt and the remaining 20% in the Maracaibo Basin. As shown in Fig. 1, the Orinoco Belt extends more than 600 km (east to west) and approximately 70 km (north to south).

The area contains rocks ranging in age from the Precambrian to the recent period, with more than 90% of the crude oil concentrated in Miocene formations. From a geological perspective, the Orinoco Belt can be considered a conventional reservoir, consisting of oil-bearing sandstones in structural traps. However, the trapped crude is classified as extra-heavy oil (8–13 °API) and is characterized by high concentrations of asphaltenes, metals, and sulfur.

Technically, extraction involves:

- Diluting oil with other hydrocarbons (e.g., naphtha, condensates) to reduce density and viscosity.

- Upgrading final products to produce commercial blends.

- Bearing higher operating costs and initial investments compared with other types of conventional oil.

Production Evolution: From Global Major to Marginal Producer

In the early 20th century, oil discoveries in Venezuela’s Maracaibo Basin launched the country’s rise as a global oil powerhouse. In 1975, the state company Petròleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA) was established, soon becoming one of the most important oil companies in the world. Throughout the 1970s, Venezuelan production reached 3.5 million B/D.

From the late 1990s to the early 2000s, Venezuela’s oil production was stable, placing the country among the world’s top five producers. In 2007, President Hugo Chávez ordered the nationalization of oil production in the Orinoco Belt, where most foreign companies were operating.

Chávez issued an ultimatum to these companies: accept minority stakes in joint ventures controlled by PDVSA or exit the country and cease production in Venezuela. Most companies, including Chevron, Eni, TotalEnergies, Statoil (now Equinor), BP, and Repsol, accepted the terms, though their investments were significantly reduced. ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips rejected the deal and were subsequently excluded from Venezuela’s oil production.

This moment represented the beginning of Venezuelan production decline. Before 2007, all operations were designed, managed, and delivered by foreign companies, which brought experience, technological development, and investments. ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips were skilled in extra-heavy oil and their exit resulted in the structural decline of infrastructure due to lack of maintenance, treatment plant degradation, and production reduction.

The country experienced another heavy blow by international financial sanctions. In 2016, the US set up several sanctions against Venezuela’s government and PDVSA, forbidding their access to the US market and the usage of Venezuelan bonds as a guarantee.

The all-time minimum production was reached in 2020 (below 400,000 B/D). Between 2023 and 2025, there was a partial recovery, with levels close to 900,000–1,000,000 BOPD, still far from the country's technical potential.

PDVSA: Operational Criticalities and Impact of Sanctions

PDVSA is a vertically integrated national oil company, responsible for upstream, midstream, and downstream. However, its operational capacity is now severely compromised. Technical expertise and sanctions avoided the intervention of investments and buyers.

Orinoco Belt crude oil is very difficult to extract. To reduce its viscosity, both thermal and nonthermal techniques can be used, e.g., steam injection or solvent dilution.

Venezuelan heavy oil requires expertise to be produced and more-complex refining equipment than lighter crudes. The most important refinery is located in the Paraguanà Peninsula (Centro de Refinaciòn Paraguanà), followed by another in Puerto La Cruz (Fig. 2). Only the Refinerìa Puerto La Cruz complex is properly equipped for oil upgrading (Winston, 2026).

To treat Venezuelan oil, refineries must be equipped with blending, upgrading, and desulfurization units, such as visbreaking (to reduce oil viscosity), coking (to convert heavy oil into lighter products), hydrocracking (to upgrade heavier molecules into lighter ones), and hydrodesulfurization (to remove sulfur, which makes oil corrosive).

Before the imposition of US sanctions, Venezuela regularly exported oil to the US because US refineries were equipped to process its heavy crude. Venezuelan oil was also considered lower quality, which made it cheaper than many alternatives. Even after the rise of light-oil production from shale reservoirs, Venezuelan crude continued to be imported to avoid sidelining older, more complex refineries designed to handle heavy grades (Gravità Zero, 2026).

US sanctions imposed by 2014 acted as a systemic constraint across Venezuela’s oil value chain. Restrictions on investment, services, and technology significantly reduced upstream capacity to extract oil and gas. Beyond the technical challenges of producing and processing extra-heavy crude, the midstream sector was further strained by insurance constraints and shipping difficulties. Sanctions also cut off Venezuela’s access to premium markets, major sources of investment, and international payment systems (Goksedef and Raanan, 2025).

As a result, exports shifted toward a model reliant on steeply discounted crude sold through shadow fleets, multiple intermediaries, and inefficient logistics, severely eroding PDVSA’s net margins. The combined effects of lost technical expertise and sustained international sanctions ultimately pushed PDVSA into financial default.

Not Only Oil: Gold and Raw Materials

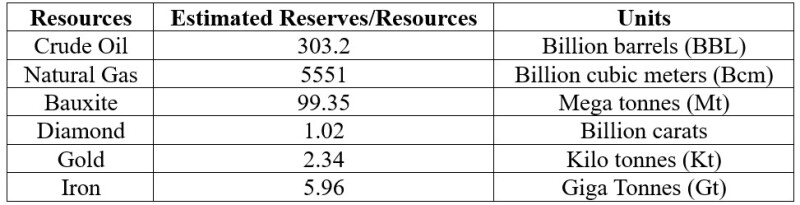

Venezuela does not only hold the record in oil reserves. Its subsurface is rich in other valuable products, like bauxite, gold, diamond, and iron. Data shows resources and reserves stored underground (Good, 2026).

It clearly emerges that Venezuela plays a crucial role also in mining activities. For years, the government suffered from strong oil dependency, and from 2016 onward there was rising concern about the raw materials sector. The Maduro government created an “Economic Military Zone,” increasing military control over mining ventures. However, gold revenues are not comparable to those of the oil sector (Ebus and Martinelli, 2022).

Nevertheless, in addition to gold and oil, coal represents a significant resource. Venezuela holds the world’s fourth-largest coal reserves, mainly located in Zulia State near the Colombian border. Although coal accounts for only 0.2% of total energy production, it is largely exported or used domestically in industrial processes. Moreover, coal exports have suffered a sharp decline in recent years (EIA, 2024).

Implications for the Global Market and Investors

Just moments after the arrest of President Maduro by the US, President Donald Trump stated that American companies were keen to invest billions to rebuild the country’s oil business. The international focus has shifted to: 1. How much investment is needed, and 2. are the largest oil reserves now open for business.

From a purely financial point of view, any investment would be high-risk considering that Venezuela is $150 billion in debt. The oil sector will require rebuilding. This process would require investments estimated to be between $60–$100 billion and a timeframe of no less than 5–7 years, ruled by stranded infrastructure and debt dilution (Watters and Dakalia, 2026).

- Chevron is the only US supermajor still operating in Venezuela and its shares jumped almost 6% after President Trump’s statements.

- ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips may invest again if sanctions are relaxed.

- Repsol, Eni, and Maurel & Prom have applied for US licenses and authorizations to export oil from Venezuela. Eni and Repsol are currently operating in Venezuela.

From the perspective of the global oil market, Venezuela represents a latent supply option, rather than a short-term variable. In the context of energy transition, Venezuelan oil is in the high-carbon/high-CAPEX range, requiring long-term strategies and integration with decarbonization solutions (efficiency, CCS, flaring reduction, etc.).

Conclusion

Venezuela remains an energy asset of global importance, but not a plug-and-play producer. The gap between in-situ resources and commercial production is the result of industrial and institutional constraints, rather than geological ones.

The Venezuelan case offers a key lesson: resources alone do not generate value. Governance, human capital, technological access, and regulatory stability are as crucial as geology in transforming barrels into sustainable cash flow. Moreover, Venezuela’s mining industry stands at a turning point, where political change could open the door to greater transparency and reform—or deepen uncertainty if instability persists.

In the medium term, Venezuela will only be able to return to being a relevant player through committed investments, political stability, and a profound realignment of its industrial model with international standards in the sector.

For Further Reading

Drilling Into the Details of Venezuela's Oil, Science Friday

The Mineral Industry of Venezuela by Yolanda Fong-Sam, USGS

Geological Synthesis of the Orinoco Belt, Eastern Venezuela by A. Isea, Journal of Petroleum Geology

Early and Middle Miocene Depositional History of the Maracaibo Basin, Western Venezuela by J. Guzman, C&C Reservoirs Inc., and W. Fisher, University of Texas at Austin.

US Accused of Seizing Venezuela's Oil as Maduro Captured in Attacks by K. Winston, S&P Global

Country Analysis Brief: Venezuela, U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), 2024

Map Shows Venezuela’s Critical Minerals That US Needs, Newsweek

What is Venezuela’s Heavy Oil and Why Does the United States Want It?, Gravita Zero

Not Just Oil: Venezuela’s Natural Resources Mapped, by Cody Good, Visual Capitalis

Venezuela’s Gold Heist: The Symbiotic Relationship Between the State by Bram Ebus and Thomas Martinelli, Bulletin of Latin American Research.

Why Venezuela Can’t Pump Its Oil, Despite World's Largest Reserves by Peter Gratton, Investopedia

Venezuela: The Oil Trade, and Who Stands To Benefit, by Thomas A. Watters and Rishabh Dakalia, S&P Global