Do you know where your wellbore is?

The question is not rhetorical, but one the SPE Wellbore Positioning Technical Section (WPTS) strives to ensure that well operators can answer with high accuracy. The ability to do so is central to safe drilling operations, optimum production, and maximum recovery of reserves. And knowing the answer depends on good wellbore survey management, a practice that frequently is deficient among drilling operations managers. It is a problem that the WPTS is trying to remedy.

Obtained by means of gyroscopic systems or magnetic systems such as measurement-while-drilling (MWD) and logging-while-drilling (LWD) tools, a wellbore survey provides essential depth and directional data as a well is drilled. The use of data from properly designed surveys enables operators to ensure that a well will have a safe pathway to its target and avoid a collision with another wellbore. Survey information is also crucial in preparing to drill a relief well, should it be necessary.

In addition, surveys provide geoscience staff and government regulators with important data, play a significant role in forensic investigations, and aid in estimating reserves. Operators also sometimes obtain post-drilling surveys to achieve an enhanced accuracy of wellbore locational data.

Safety and Economic Benefits

Because the highest priority is to drill wells safely, conducting a wellbore survey is first and foremost a safety practice. However, the WPTS believes that many people in the industry fail to recognize the full economic benefit that good survey practice adds to drilling projects by reducing the uncertainty of achieving the intended well path. Thus, they underestimate the economic cost of inadequate survey practice.

The growth of pad drilling, in which multiple wells are drilled from the same location and spaced closer together, accentuates the need for good wellbore survey practice for safety and economic reasons.

“If you don’t know where your well is, how do you know what your reserves are?” asked Robert Wylie, product line director of Dynamic Drilling Solutions at National Oilwell Varco.

Reflecting this theme, Wylie moderated a WPTS topical luncheon titled “Why Did Your Reservoir Just Move?” at the 2014 SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition (ATCE). Good survey management drives increased value for wells, reservoirs, and companies, he said.

One size does not fit all in the design of a well survey. The operator must assess its reservoir goals, safety needs, and risk aversion in drilling the well, and the survey’s potential for enhancing the well value, and then design a survey program to meet those needs, Wylie said.

The problem is that operators conducting MWD surveys often obtain data only on the inclination, azimuth, and measured depth of the wellbore. A full MWD survey should include raw data from individual sensor readings, from which important wellbore survey accuracy information is obtained on magnetic field strength, total gravitational field, and magnetic dip, Wylie said. And the survey data should be confirmed for quality control by two independent tool types in every section of the well as a best practice, he said.

The reason why some operators conduct an incomplete survey is to save rig time and expense, Wylie said. Although MWD tools obtain the needed raw data, downloading and processing the information takes an additional 90 seconds or so. Repeating that process for each section of the well as it is drilled could add USD 10,000 to USD 30,000 to the cost.

Shortcuts Are Shortsighted

“Some drilling operations managers view these savings as a way to beat timetable and budgetary goals, but this is shortsighted,” Wylie said. “The risk that poor surveying poses to well and reservoir production greatly exceeds the economic value of the savings, to say nothing of the risk of a rare but potentially disastrous wellbore collision.”

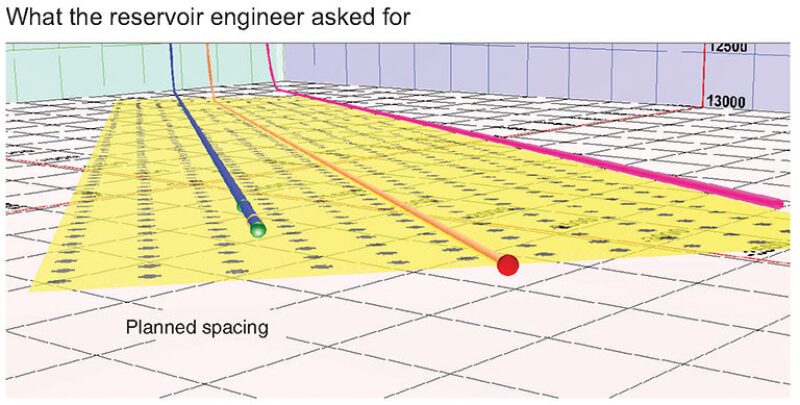

He stressed the importance of good survey management for optimal spacing of multiple wellbores. For example, in a shale project that Wylie cited during his presentation, an operator who had planned to drill three wells from a pad determined that under standard survey management, the risk of a wellbore collision was high.

The operator had three options, Wylie explained.

- Plan the wells farther apart but not optimally spaced for reservoir drainage, which would leave reserves unproduced between the wells.

- Shorten the planned middle well to ensure collision avoidance, which would reduce reservoir exposure and leave reserves unproduced.

- Spend the additional money for a better wellbore survey program, thus reducing the margin of survey uncertainty and ensuring safe drilling of all three wells with optimum spacing for full oil recovery.

“The operator chose the third option, improving the well economics by several million dollars,” he said.

Wylie also cited the analyses of North Sea and West African reservoirs in which a 1-ft error in the true vertical depth measurements for specific wells translated into shortfalls of 60,000 bbl to 100,000 bbl in recoverable oil reserves. In another case involving production by steam-assisted gravity drainage, placing the wellbore 1 m deeper would have added USD 1.8 million worth in recoverable reserves, he said.

Wellbore Positioning Workshops To Be Held in Galveston, Texas

The SPE Wellbore Positioning Technical Section (WPTS) has slated two workshops on wellbore positioning for November in Galveston, Texas. The Industry Steering Committee on Wellbore Survey Accuracy (ISCWSA), which is affiliated with the WPTS, is cosponsoring the events.

A 2½-day applied technology workshop (ATW), titled “Well Placement and Intersection Best Practices: Maximizing Value, Minimizing Risk, Managing Safety,” will be held on 9–11 November at the San Luis Resort, Spa, and Conference Center.

John de Wardt, president of De Wardt & Company, and John Wright, global relief well adviser at Wild Well Control, are co-chairs of the program, which will include presentations by industry experts and working sessions to build expertise in best practices for intercepting geological targets, avoiding adjacent wells, planning relief well trajectories, and managing positional uncertainty to improve subsurface modeling correlations.

“Many operators still take their wellbore position accuracy for granted,” Wright said. “Only after a major mishap, such as a well collision or poor production because of misplacement in the reservoir, do they focus on ‘Why did that happen?’

“Engineers need to allocate time in their well delivery process to assess the risk of wellbore position uncertainty for its potential consequences for health, safety, and the environment and for production objectives. That assessment would dictate the survey program and quality control required to mitigate the risk. The mission of the WPTS/ISCWSA is to provide those engineers with the training and resources necessary to make that assessment.”

The ATW will also hold a relief well drilling competition with a simulator that participants will be able to run on their laptops.

“This simulation takes the attendee deep into the world of uncertainty, ranging, and risk, without the need to mop up a catastrophe afterward,” Wright said. “You will be surprised just how wrong your assumptions were about the right way to preplan your contingency wells and the ability of modern technology to achieve intercept goals when they are used and applied correctly.”

A second ATW, titled “Surface and Wellbore Positioning Errors Impact Subsurface Models and Reserves Estimates—How Much and How Serious?” will be held from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. on 12 November at the San Luis conference center. De Wardt and Jon Stigant, owner of the consultancy Stigant Enterprises, are co-chairs of the program, which will feature expert presentations followed by a panel debate.

“Subsurface models contain potentially large errors because of surface and wellbore position uncertainties resulting from inadequate surveying practices, especially through the cross correlation between wells,” de Wardt said. “Such errors can lead to large impacts on these models and on reserve estimates, impacts that have never been fully assessed. The ATW will break new ground by assessing the scale of the problem and developing cross-disciplinary initiatives that interested parties can launch to tackle these issues.”

Both workshops have been designed to accommodate the itineraries of people visiting clients and head offices in Houston as well as the convenience of industry professionals based in the Houston area. Engineers responsible for drilling, drilling management, and relief well contingency planning; geoscientists responsible for operations and reservoirs; well surveying specialists; asset managers; and risk managers are encouraged to attend the workshops.

Additional program information on the second workshop will be available online at a later date.

True Along-Hole Well Depth

In another presentation at the ATCE, Ton Loermans, a former engineer and petrophysicist at Shell and retired petroleum engineering research consultant at Saudi Aramco, addressed quality control for measuring true along-hole well depth.

For giant fields, oil-in-place differences resulting from relatively small depth errors may become very large. “Few people will believe such variation of oil in place might be as much as 1 billion bbl per foot of error, which is an extreme case, but differences of many, many—more than just a few score—millions of barrels of reserves per foot of depth uncertainty are not unheard of,” Loermans said. “Hence, one of the main objectives is to bring that uncertainty of depth down and eliminate it from our risk-in-development planning.”

An error of a few feet could mean the difference between an economic project and a nondevelopment. For example, such an error in the incremental development of a small block could lead to the need for two wells instead of one, which would unacceptably double the cost for a given level of recovery.

As an extreme case of logging depth problems, Loermans described a giant oil field that had to be abandoned some years ago with 75% of its reserves still in the ground. “The reason for that was essentially some boo-boos in handling wireline depth,” he said.

The general problem of accurate logging depth calculation depends on proper stretch corrections in the wireline cable and drillstring. Wireline logs are generally corrected for stretch, but the calculations were developed many years ago for smooth vertical wellbores and are inappropriate for the horizontal wells of today, Loermans said. LWD logs rely on driller’s depth measurements without stretch corrections.

Some people believe that reliance on driller’s depth is not a problem, assuming the errors are consistent. However, there is no consistency in the errors of driller’s depths, Loermans said, and in many cases, the failure to make proper stretch corrections has resulted in wellbores that are not landed at the supposed depth. The distance to the reservoir oil/water contact will differ from the planned/optimal distance, and the wells will become prematurely uneconomic years later because they water out a few months early.

Best practices in wellbore survey management have not always taken a high priority. “The troubles with inaccurate depths only show up long after drilling the well,” Loermans said. “So the people in control of specific drilling operations, the ones who will have to do the extra work and spend the extra money to improve the procedures, probably won’t be in control of those operations to see the benefits.”

Still, the corrections are straightforward. “We have the mathematical tools; they go back to [Robert] Hooke, a contemporary of Newton in the 17th century. Proper correction is a piece of cake really,” he said.

Industry performance could improve through collaboration between operators and service companies to discuss their problems, write new equations, and update procedures, but operators must be willing to share data and information.

Sharing could be a sticking point because operators are often reluctant to discuss issues such as mistakes and “near misses” even internally. “Too many people don’t tell enough about mishaps,” Loermans said. “Higher management may only half know what the problems are because people don’t tell them enough. They may be discouraged from doing so by their supervisors, and people outside the company won’t know either. So nobody learns very much.”

Additional regulation that requires operators to release raw log data, interpreted data, and reports, after a certain permissible delay, could help, he said.

Wellbore Positioning eBook Is Available

The eBook, Introduction to Wellbore Positioning, published by the Industry Steering Committee for Wellbore Survey Accuracy (ISCWSA), is available on http://www.uhi.ac.uk/en/research-enterprise/res-themes/energy/wellbore-positioning-download.

The industry standard publication was written to provide better educational material to support the understanding of borehole surveying issues. It was published through the research office of the University of the Highlands and Islands and may be used for free.

The ISCWSA is a committee of the SPE Wellbore Positioning Technical Section.

Put Well in Right Place

Also at the ATCE, Angus Jamieson, professor of offshore engineering at the University of the Highlands and Islands in the United Kingdom, said that drilling should not be viewed as though there were “a starting gun.” Rather than tell the contractor, “Finish this well as fast as you possibly can and we’ll pay you a bonus,” he said, “how about putting it in the right place so that we get the production that we’re looking for. That’s where the rewards should lie. Because by the time the well waters out 6 months early, the contractor who drilled it is long gone.”

Jamieson told of one offshore relief well project in Asia where the well that needed to be intercepted had not been surveyed, which added months to drilling the relief well. “They were 9 months on that well, and the survey company they could have used on the original well might have cost them USD 20,000,” he said. “Did they save USD 20,000?”

For spending such a relatively small sum, operators can greatly reduce the uncertainty of wellbore positioning, Jamieson stressed.

“There are four major corrections that we can apply: stretch corrections, sag corrections, in-field referencing corrections, and magnetic interference corrections,” he said. “They are very easy to fix. We can get marvelous accuracy out of them. The problem is that the company that’s selling you the service is also the company that’s telling you that you need it. So it’s very difficult, a tough sell. We need to change the mentality in the industry.”

The small additional spending should be compared with the much greater value of the production likely to be preserved. And a good understanding between geoscience and drilling staffs of survey requirements is needed to design fit-for-purpose programs, he said.

“If we don’t get the message out that wellbore positioning is worth spending money on,” Jamieson concluded, “we will continue to waste reserves and occasionally risk lives.”