While the easy oil may be gone, exploring existing basins and reprocessing older seismic data still yields a lot of value.

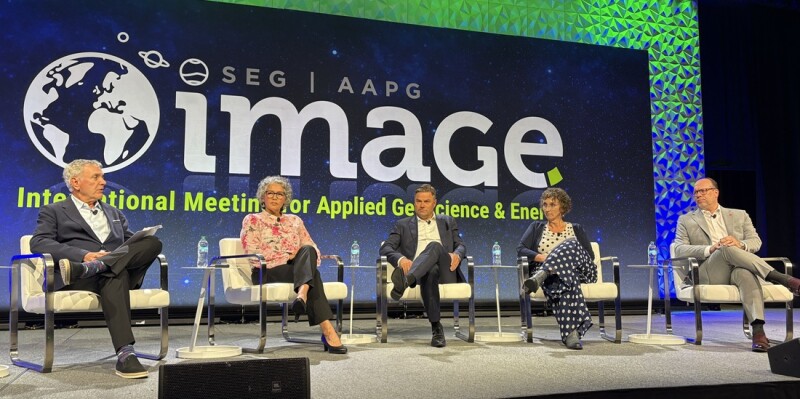

During the opening session of the International Meeting for Applied Geoscience and Energy on 25 August in Houston, speakers from Shearwater, TGS, Chevron, and Murphy Oil acknowledged the increasing difficulty of finding new reserves and understanding the complexity of the reservoirs where those hydrocarbons exist.

TGS Chief Executive Officer Kristian Johansen said, “After you find the easy oil, you have to look for the more difficult reservoirs.”

Typically, the industry looks for more oil near known oil accumulations, but technology makes it possible to discover oil in other places.

“New technology is a key driver to this because new technology allows you to explore in areas where you haven’t explored before,” he said.

But technology also makes it easier to search for oil in known basins, such as in the Gulf of Mexico, which was recently renamed Gulf of America. There, Johansen said, seismic has been shot many times over the years and images can be reprocessed with artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to reveal more detail about potential reserves.

“You see new imaging technologies that can definitely rejuvenate the value of old data,” he said.

Chris Olson, vice president and head of exploration at Murphy, noted fewer exploration wells are being drilled now compared with the industry’s past. That means, he added, that fewer large discoveries are being reported.

“It takes a lot of discoveries to make big discoveries happen,” he said.

And when discoveries are made, the reservoirs tend to be fairly complicated.

“Just about every reservoir I’ve ever helped discover, it’s inherently more complex than you think going into it,” he said.

A large part of understanding complex reservoirs happens through appraisal activity, he said.

Danielle Carpenter, general manager for the global exploration review team at Chevron, said she’s spent half her career in exploration and half in development activities.

“When we do exploration, we make lots of simplifying assumptions. And when we develop it, we actually find it’s much more complex. So, the devil’s always in the details,” she said.

Tanya Herwanger, senior vice president of strategy and new markets at Shearwater, said the subsurface isn’t the only complication the industry faces. Water depth and harsh environments also complicate exploration and production activities.

“There is also aboveground complexity, things like increasingly protracted permitting, increasing environmental requirements, and, even when permits are issued, you don’t know if they’re going to stand. And you had some recent examples on that. So, there’s complexity upon complexity upon complexity,” she said.

Collecting data brings its own challenges, she added. What’s most important, she said, is having a solid understanding of the objective for collecting the data.

“What are you trying to achieve with that survey? What’s your goal? Is it monitoring? Do you have a very specific problem? Are you just at the early stages of characterizing that reservoir?” Herwanger said.

Understanding the purpose makes it possible to maximize the value of the data, from the acquisition stage by choosing the right tools for the problem but also during processing.

“The more complex the problem, the greater the level of engagement that’s required between the seismic company and the operator,” she said.

It’s also important that the goals of the operator not get muddled by the procurement department, which may be required to award contracts to the lowest bidder, Herwanger said.

“You’ve got high complexity, high demand for high-end technology and a procurement system that doesn’t really support that need. So, there’s a mismatch sometimes,” she said.

When exploring, Olson said, it’s important to be open to working wherever the oil is.

“I think you really need to not say, ‘I’m only going to be in this country’ or ‘I’m only going to target this margin,’ ” he said. “You have to be open to basins that can work. You have to cast a wide net. We don’t shy away from a specific play.”

Carpenter said it’s important to fill the exploration hopper with lots of different opportunities.

“You’re not going to put all your eggs in one basket; you’re not going to throw your eggs in one basin. You’re not going to think about only one play. You want a diverse portfolio to choose from. You don’t know which ones are going to win and which ones are going to work,” she said.

Part of the fun of working in exploration is solving the puzzle of where the reserves are, she said.

“I became a geologist because I’m a puzzle person,” she said, adding that, in exploration, it’s likely that the explorers are trying to put together the puzzle with only half the pieces, if they’re lucky.

“Explorers are those that create something out of nothing,” she said.