BHP Billiton lost billions during its foray into US shale, but that doesn’t mean it has soured on oil and gas.

Since the Melbourne-based firm announced in July the sales of its assets in the Permian Basin, Eagle Ford Shale, and Haynesville Shale, many have wondered if it would leave oil and gas altogether. But Skip York, BHP head of strategy and market intelligence, petroleum, assures that “BHP is still very bullish on the petroleum story as a natural resources company.”

That’s because there will continue to be value in conventional assets driven by natural declines and the oil supply-demand imbalance, he explained. While demand may peak, its decline will be much slower than that of supply, which tends to take steep dives. “And somebody has to produce incremental barrels every year,” York said during a discussion this week at Rystad Energy’s Annual Summit in Houston.

“We aren’t staying in petroleum because we are naïve about where the demand profile is going,” he said. “We’re staying in petroleum precisely because we do understand what the demand profile looks like.”

Companies that can acquire assets at a low cost and operate with high uptime and minimal spending will come out ahead, he said, “because the marginal barrel is going to be so much more expensive than the operating cost of the barrel that’s [already] online.”

All this means BHP is content to focus on deepwater exploration and development. While it is counterintuitive these days to stick by a business with long-cycle times and high front-end costs as investors demand capital discipline and free cash flow, BHP sees “a cost environment that’s going to encourage development,” he said.

A report from Rystad indicates that close to 100 offshore projects will be sanctioned this year, up more than 50% year-over-year. The consultancy expects offshore investments to rise in 2019 after 4 straight years of contraction.

“Without going into the numbers, we have more identified petroleum opportunities than we have the ability to execute,” York said, meaning the company can be selective in how and when it carries out projects. He noted that it is his group’s job to “keep bringing new petroleum projects to that corporate funnel and keep the petroleum part of BHP competitive within the broader part of the corporation.”

It notably added to the funnel in 2016 when it outbid BP to partner with Pemex and serve as operator of the deepwater Trion field in the freshly opened Mexican sector of the Gulf of Mexico. BHP plans to spud the first appraisal well there late this year or early next. In the US gulf, the firm holds interests in four fields, serving as operator of the deepwater Shenzi and Neptune fields.

BHP also has interests and operatorship of several fields off its native Australia, including a stake in the North West Shelf project, as well as off Trinidad and Tobago, Algeria, and the UK. “We’re very happy with the deepwater portfolio we have and the prospects we have going forward,” York said.

But finding barrels of oil offshore will continue to be a big challenge for the industry, he added. “The industry has struggled with exploration success going on almost a decade now. That has to reverse itself not just on a company basis but on an industry basis” because shale will plateau—and could fall hard given its type curves—and at some point more sustainable production will be needed. “You need more of those long-life assets, and those long-life assets are in the offshore space.”

“We’ve got to figure out what it is we are missing,” he said. “We are looking in places where our experience tells us to look, but what’s the new tweak that has to happen" to allow operators see geology in a new way?

Advising Against Shale

York was asked by an audience member at the event if he would discourage new companies looking to enter the shale sector from doing so. His answer, after giving the question some thought, was “yes.”

For one, he said, “it’s a pretty well staked-out place.” New entrants need large, contiguous acreage positions to accommodate long laterals. Shale development also comes with a steep learning curve that existing shale operators took years to figure out. “If you’ve got no alternatives, then maybe it is your best play. But it is hard for me to believe that if you are not in there today, you can go in there and create a materially valuable position,” York said.

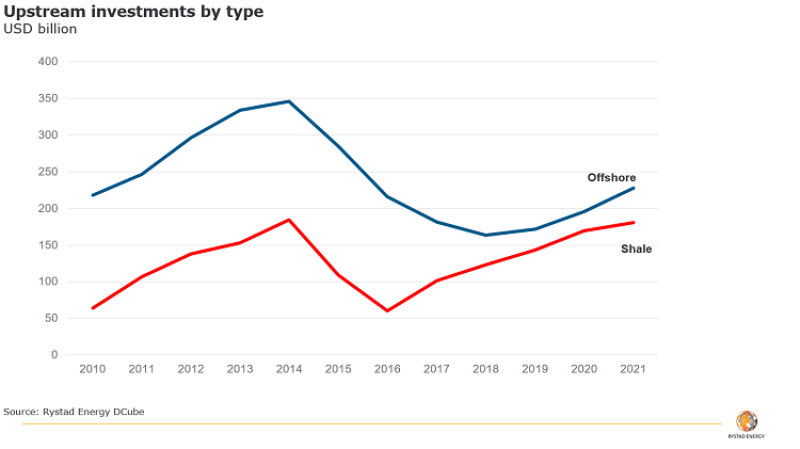

Rystad expects a downward trajectory in shale growth in the coming years amid logistical challenges, takeaway capacity bottlenecks, and growing oversupply in the proppant and fracturing market. As a result, shale investment will grow at a slower pace than previously expected and end up at about $120 billion this year compared with $160 billion for offshore.

“Shale has thus lost some momentum at a time when investors have again found an appetite for the offshore domain, stimulated by a steep reduction in offshore costs and breakeven levels, which in turn have been driven by favorable unit prices,” said Audun Martinsen, Rystad head of oilfield research.

BHP’s shale experience, of course, wasn’t a good one. While the company’s sales netted a better-than-expected $10.8 billion, it bought into the plays earlier this decade for almost double that amount. When the commodity price downturn hit, the company lost billions in write-downs. It reported its intention to divest the assets last year amid pressure from activist investor Elliot Management.

The company ultimately concluded, though, “not that shale is a bad business” but that its assets were “probably more valuable to someone else,” York said. Citing bank estimates from a year ago that the assets would sell for $7 billion, he noted that BHP was able to capture a better price because oil prices were strong and potential buyers’ interest rose as they were able to see the assets in detail from the data rooms.

“The ultimate value of the shale portfolio was our Permian acreage,” he said. As an early mover into the basin, the company was able to acquire its position for “somewhere in the neighborhood” of $800–900/acre, he said. The acreage was appealing given its strategic locations for the potential buyers.

As BHP is leaving the Permian, fellow deepwater players ExxonMobil and Chevron are doubling down on development activity there. ExxonMobil currently has the most rigs working in the basin.

The difference in their approach to the basin, York said, could be that “they have a belief that they can make the Permian look like a megaproject,” similar to a deepwater one, “because both of those companies are very good at executing large, capital-intensive projects.”

“I’m going to say it’s a strategic gamble. But they’ve got a strategic perspective that’s different from ours, and we’ll play this out over time and see how successful ExxonMobil and Chevron are at doing it,” he said. Those companies are also more equipped to bear risk, York noted, because of the diversity of their portfolios, giving them more leeway to try to “crack the code” in the basin.