Oil is likely to dominate the energy mix for the next decade, and natural gas demand over the next 25 years depends on the speed of the energy transition, according to an annual report from BP.

The BP Energy Outlook 2025, published 25 September, considers two key scenarios that could develop over the next quarter century. In either scenario, or any pathway in between, factors such as the shift toward electric vehicles, feedstock demand, power generation demand, and changes in energy efficiency will play a role. Geopolitical fragmentation, such as that related to the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, also could affect the future of the energy system.

Spencer Dale, BP’s chief economist, said during the 25 September webcast discussing the outlook that it is unlikely the world will follow either scenarios laid out in the report — a Current Trajectory scenario and a Below 2°C scenario —rather, the scenarios make it possible to develop key insights about how the energy system might develop over the next 25 years. These scenarios make different assumptions about the speed and nature of the energy transition.

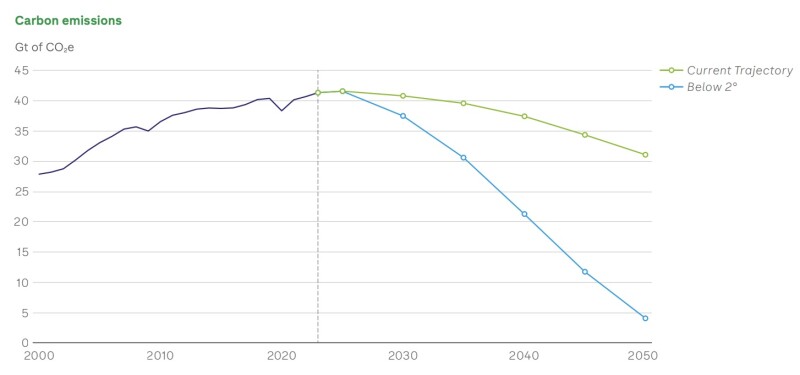

The Current Trajectory scenario is intended to reflect the broad pathway on which the global energy system is traveling and suggests CO2 equivalent (CO2e) emissions will remain roughly flat around their current levels throughout the remainder of this decade before gradually declining throughout the 2030s and 2040s. By 2050, carbon emissions are only around 25% lower than they are today under this scenario, which considers policies in place as well as trends and decarbonization pledges.

The Below 2° scenario explores the energy system along a path in which net emissions decline by around 90% from their 2023 level by 2050. This scenario assumes a significant tightening in climate policies alongside shifts in societal behavior and preferences.

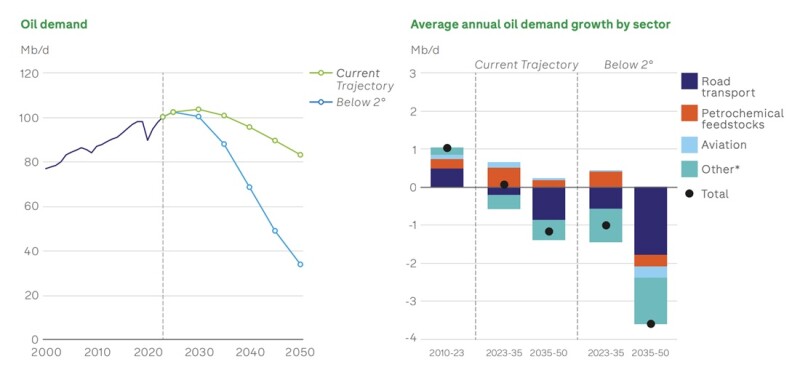

Gareth Ramsay, BP’s head of the energy transition and systems analysis, said it is likely oil will play a major role in the energy mix for a while in either scenario.

“Oil carries on playing a central role in the energy system for at least the next 10 to 15 years. And that matters a lot for the investment that we’re going to need,” he said. “Because of the way that output of oil fields naturally declines, we’re going to need hundreds of billions of dollars of new investment every year to meet these kinds of levels.”

There is also a change in how that oil is likely to be used, compared with the past when “the single biggest driver of oil demand growth in the global energy system has been rising demand for oil in road transportation,” he said.

In both scenarios, oil demand for road transportation falls, partly because of the shift toward electric vehicles and more efficient vehicles.

On the other hand, feedstocks are “more important than people realize,” he said.

“The biggest single driver of oil demand growth in the future is not oil being combusted. It’s oil being used as a feedstock, what we call the petrochemical sector, particularly for the production of plastics as well as other oil-based materials,” Ramsay said.

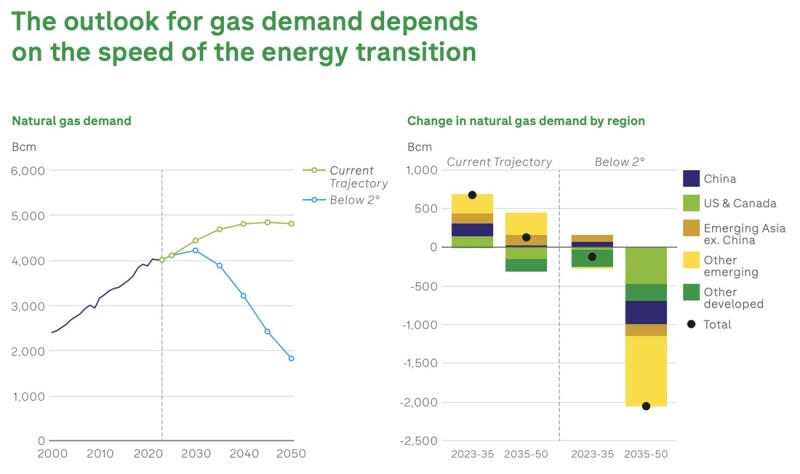

Demand for natural gas in the two scenarios is more sensitive to the pace of the energy transition, although demand for natural gas in both scenarios is expected to be quite strong over the next decade, he said. In the current trajectory scenario, gas demand rises, while in the below 2°C scenario, a push for decarbonization causes a decline in natural gas demand.

“In practice, both of these forces are likely to be at work in the future, so the outlook for natural gas is going to depend on the relative strength of these two forces,” he said.

There is an expectation that, under both scenarios, electricity demand will continue to increase, with some of the demand powering electric vehicles and data centers. The US, for example, is facing higher electricity demand than in the past, partly because of data centers powering artificial intelligence (AI).

Ramsay, who is slated to become BP’s chief economist in 2026, said the effect of AI on energy is unlikely to hinge on how much power data centers need.

“AI won’t just affect energy demand. It could have equally big implications for the supply of various types of energy and the efficiency of many parts of our energy system. So, just the bottom line here, if we’re going to think about AI and energy, we do need to think much wider than just data centers,” he said.

AI could make it possible to operate the energy grids more efficiently, he said.

“In 10 years’ time, when we think about the implications of AI for our power systems, we may well not be talking nearly so much about data centers” because they will be operating more efficiently, Ramsay said. That said, he noted significant investment in the power grids still will be required under either scenario.

While power demand is likely to increase in both scenarios, wind and solar are expected to become a central foundation of the energy system.

“Added together, they generated about 15% of our electricity last year. By 2050, they account for more than half of global power generation in Current Trajectory and more than 70% of it in Below 2°,” he said.

He said solar grows faster than wind in either scenario because its costs decrease more quickly, it’s faster to deploy, and it has greater policy support.

Geopolitics and the Trilemma

Dale said increasing geopolitical fragmentation has some possible implications for how the energy transition unfolds. For example, he said, increasing fragmentation could prompt countries to reduce their exposure to international trade in a bid to become more self-reliant.

“A shift to greater self-reliance might dampen the growth on international trade as countries move their supply chains back home or restrict them to countries or regions most politically stable or aligned with them,” he said.

The cascading effect could lead to weaker economic growth first and lower energy demand second.

“Increased geopolitical fragmentation may also heighten the importance of energy security as countries seek to reduce their dependency on imported energy and energy technologies,” Dale added.

This focus on energy security could have consequences for the energy transition, such as leading to the use of more low-carbon technologies or leading come countries not to import energy.

“Increased geopolitical fragmentation might also lead some countries to place less weight on climate and sustainability goals. In part, this simply reflects the nature of the so-called energy trilemma. If countries place greater weight on energy security, it necessarily implies they must place less weight on the other two elements of the trilemma, either energy affordability or energy sustainability,” he said.

He went on to note that increased fragmentation affects different countries in different ways but that, at a global level, they tend to offset one another.

Energy Efficiency

Dale also said a continued lack of improvement in energy efficiency could affect demand over the next decade. From 2010 to 2019, energy efficiency averaged about 2% a year, meaning, each year, the world needed 2% less energy to produce the same level of output. However, he said, over the past 5 years, energy efficiency has only averaged 1.5%.

“The causes of this recent weakness are not fully understood,” he said, although a recent International Energy Agency study suggested increasing manufacturing-intensive industries combined with increasing intensity of extreme weather could be at play. Without understanding what’s caused the decline in efficiency, he said, it’s hard to know how quickly gains in efficiency might revert to the historical rate.

Delayed and Disorderly

In BP’s Energy Outlook 2024, the company warned that delayed efforts to decarbonize would result in a costly and disorderly energy transition.

During the 2025 webcast, Dale said the Current Trajectory scenario would use up the 2°C carbon budget by 2040.

“It’s actually a little bit worse than that because, if you stay on that pathway and you’ve exhausted the carbon budget 2040, you’ve still got carbon emissions at 30 or 35 gigatons,” he said.

To get close to net zero, he said, the world needs to move faster.

“You need to move away from the current pathway onto something which is a faster, more rapid decarbonization pathway similar to Below 2° by the early 2030s. And, if you haven’t moved off that carbon budget, that pathway, onto something quicker by the early 2030s, your ability to stay within a 2° carbon budget without undertaking a costly or disruptive transition becomes harder and harder.”