The carbon capture industry faces a turning point as temperatures rise and governments shape climate-change-related policies.

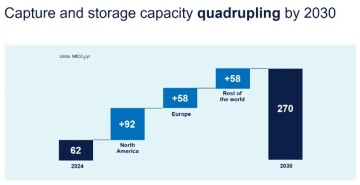

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects face multiple barriers before they ever reach final investment decision (FID), and support through policy can make or break a project. CCS capacity is expected to quadruple from 2024 to 2030, and DNV forecasts CCS will grow from its current level of 41 million tonnes/year to 1.3 billion tonnes/year of CO2 captured and stored in 2050. Yet, DNV said in its “Energy Transition Outlook: CCS to 2050” forecast released earlier this month, that’s not enough to achieve net-zero goals.

Ditlev Engel, CEO of energy systems at DNV, said during a 12 June webcast about the forecast that CCS is currently at a turning point.

The “heavy lifting” for carbon capture development has so far been focused through oil and gas production, he said, but, over the longer term, CCS will increasingly address hard-to-decarbonize emissions from industries such as cement and steel production.

“The biggest barrier to the acceleration of CCS deployment is policy uncertainty. Policy shifts, not technology or cost, have been responsible for many CCS project failures; however, policy support for CCS is firming across most world regions. After many years of hard work, we have reached this inflection point for CCS,” Engel said.

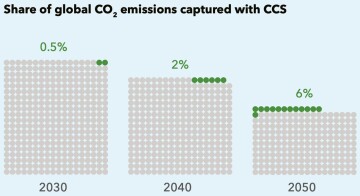

Jamie Burrows, DNV’s global segment lead for carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS), said during the webcast the current CCS project pipeline is strong but the industry must scale “very significantly” from expected numbers to reach net zero—that is, the state where the amount of human-caused greenhouse-gas emissions released into the atmosphere is balanced by an equivalent removal of those emissions from the atmosphere. As it is, he said, it is estimated that CCS will capture only 6% of global CO2 emissions in 2050. While that is 30 times current capacity, it is far below what is required to achieve a net-zero outcome, he said.

Burrows stressed that, in addition to having policy support, CCS projects must be economically sound.

“The cost of emitting CO2 has to be greater than the cost of capturing and storing,” he said.

Barriers to Scale

Burrows said the main barriers the industry faces are public perception, cost, and policy, while the technology itself is well proven.

“We’ve been injecting CO2 into the subsurface for over 50 years now,” he said.

Burrows acknowledged the public often has questions about CCS technology and use and said the industry must ensure that members of the public see benefits as CCS is deployed around the world.

CCS “is not inexpensive. There is a substantial cost associated with building and operating a capture plant that has to be addressed for us to move ahead with CCS,” he said.

In order for companies to confidently invest in expensive CCS projects, certain policies and regulations need to be in place, he said.

“We know that projects cannot move ahead without some level of government support,” Burrows added. “If it’s not legal to inject CO2 into the subsurface, projects cannot proceed.”

Storegga CEO Tim Stedman said during the webcast that clear, stable frameworks from governments are critical because uncertainty is “the killer” of CCS projects.

“People want to deploy money in this space. But confidence is key. Confidence is something that is the marked opposite of uncertainty,” he said.

He noted governments from Malaysia, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States are moving forward with CCS policies in different manners and that these are the four regimes Storegga has selected to work within.

“We want to pick a small number of regulatory frameworks to work within and to position ourselves such that, as those develop, and as the uncertainty reduces, and as you can address project on project risk with emitters, we’re able to move with pace through to FID and beyond,” he said.

Nor A’in Md Salleh, general manager of CCS at Petronas, said the government is heading toward a supportive policy that will enable CCS in the country. In general, she said, it’s important to establish a CCS ecosystem that will help derisk future projects.

When it comes to risks, sharing them is an approach that can help, Sigrid Borthen Toven, vice president for low carbon solutions at Equinor, said during the webcast.

“We, as an industry, we can take risks, but we cannot take all the risks alone,” she said.

Equinor, for example, is one of the partners, along with Shell and TotalEnergies, in the Northern Lights CCS project offshore Norway. Phase two of that project got the go-ahead earlier this year.

Tim Heijn, the managing director of Northern Lights, said that interest in securing access to the project’s CO2 storage space is high.

“If we would be able to sign contracts with everyone that we discussed at very mature levels with, we won’t have enough capacity,” he said.

Elsewhere, Occidental’s 1PointFive said it expects to have its Stratos direct air capture (DAC) facility online in Texas later this year to accept 250,000 metric tons per year, which is half the facility’s total planned capacity. The rest of the capacity is expected online in the middle of 2026.

William Barrett, vice president of product development at 1PointFive, said during the webcast that the company is working to make the DAC technology more efficient and less costly, which is critical for helping the technology achieve a level of sustainability. The company believes DAC technology, deployed at scale, can meaningfully contribute to addressing climate change.

“We believe advancing technology like direct air capture is going to take some government incentives, and we’re working to show the value in that. So, we must demonstrate how early incentives can help create longer-term commerciality, so the technology is sustainable and not always a cost,” he said.

With the project being completed in phases, 1PointFive is able to take advantage of research advances by scientists at its Carbon Engineering innovation center in Canada that can improve efficiency and drive down costs of the DAC approach, he said.

“We’re already seeing changes in better efficiencies, even in this first construction phase,” he said.

The Stratos first phase uses 34 air contactors, but the second phase will only need 24 contactors to accomplish the same actions. The result, he said, is reduced capital expenditure for construction as well as reduced operating expenditure.

“Removals are here to stay. It’s an essential part of addressing climate change,” Barrett said.

Evolution of CCS

DNV projects CCS will evolve over time, with an initial focus in fossil-fuel emissions but moving into hard-to-decarbonize sectors such as cement and steel, Burrows said. Both carbon dioxide removal and nature-based solutions will be needed, he said.

Stedman said the expectation is that fossil fuels will continue to play an important role in the energy mix for some time and that can be made less damaging to the environment through CCS.

“I always like to emphasize this is about ‘and.’ It’s not ‘or.’ You know, we have a massive, massive problem in front of us. You need to throw everything at it,” he said.