Second only to the power and utility sector, the oil and gas industry is experiencing a higher frequency of cyber attacks than any other industry. The vast majority of penetrations are in the information technology (IT) networks that run a company’s daily business.

Timothy Nguyen, the chief information security officer of BHP Billiton’s petroleum division, said there is no question that the industry is facing a “tremendous amount of cybersecurity attacks” these days. He pointed to a study by PricewaterhouseCoopers that showed that the number of reported industry cyber attacks in 2013 topped 6,500—an increase of 179% from the previous year.

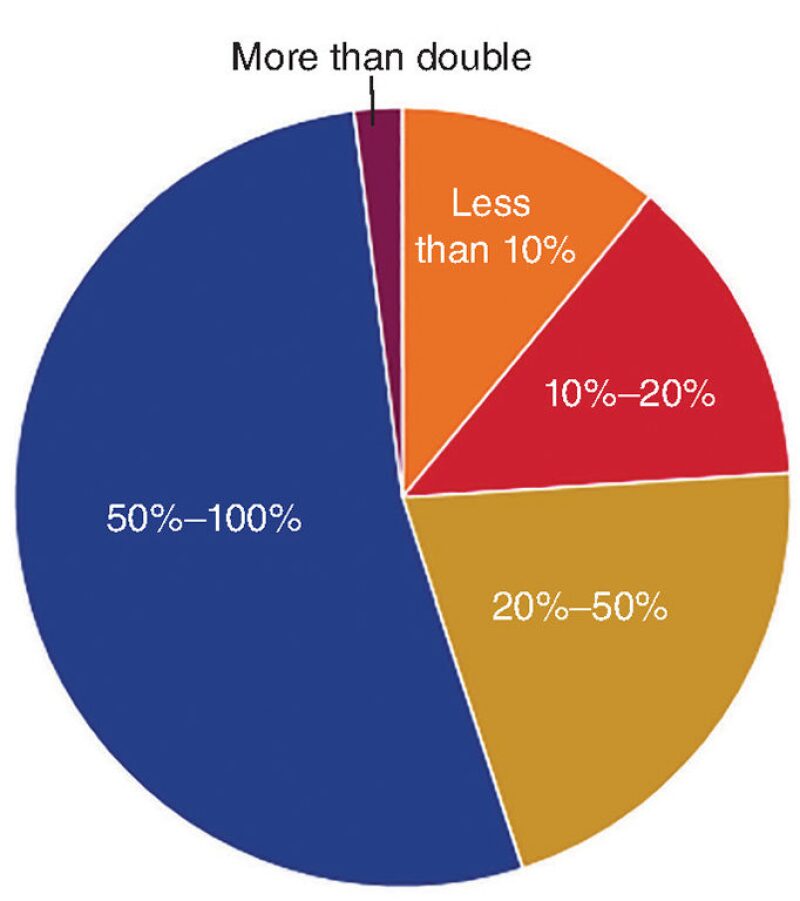

Similar figures for 2015 are unavailable; however, a survey carried out last November indicates that the rate of attacks remains on an upward trajectory. Commissioned by cybersecurity firm Tripwire, the survey polled IT professionals working in the energy sector across the US.

More than 80% of those working for oil and gas companies said the number of attacks continues to increase year over year. About half said the rate had jumped by 50% to 100% in just the past month alone. Highlighting the sophistication of recent attacks, most of those polled also said that they were “not confident” in their company’s ability to detect all the cyber attacks.

Tim Erlin, director of security and IT risk strategy at Tripwire, said the survey results show that as the number of successful attacks increases, detection rates keep falling. “That’s a combination that is particularly dangerous,” he said. “When you feel like you can’t see what is going on in your network—that you don’t have the tools to gather data—you clearly can’t protect everything like you would like to.”

What the survey did not explain are the number of unique challenges facing the industry when it comes to cybersecurity. Philippe Flichy, senior digital oilfield adviser at Baker Hughes, pointed out that unlike other global industries, in each oil and gas project there may be a very large number of companies and vendors working together and sharing confidential information.

Making sure every company is securing their piece of the data pie has become a complex task. And because cybersecurity is an expensive operation, smaller firms tend to be at a disadvantage. The current downturn has also seen a fair number of IT professionals leave the industry which has increased the workload of those who remain. “I am quite optimistic that the oil and gas industry is moving in the right direction,” Flichy said. “At the same time, it’s tough because there are less people on deck.”

What They Want

Estimates range between an average of 200 to 220 days from when a company’s system is breached to when it becomes aware of the breach. This gives attackers more than enough time to move through a network and carry out their objectives, which vary depending on their motives.

Starting at the lowest end of the risk profile are the relatively unskilled individuals called “script kiddies” who take publicly available bits and pieces of malware code from other hackers and launch them against companies to test their own abilities.

Then there are more skilled criminal hackers who have tailored their skills for financial thievery and the extortion of companies and employees. Some are looking to suck up thousands of personnel files containing financial information that can be sold on the black market. Criminal hackers are also fond of holding data or access to personal computers hostage by using malware to encrypt files until a ransom is paid.

The so-called hacktivists groups involve a collective of hackers focused on making political or social statements. The most popular such group is known the world over as Anonymous, which has for the past few years launched an annual attack against various oil companies called “Operation Petrol.” There are growing fears that cyber terrorism may use similar strategies to cause widespread disruptions.

“Then you have the nation state,” Nguyen said. “They want to know what oil and gas companies are up to and what companies are doing.” He explained that state-sponsored efforts are after intellectual property and gathering intelligence for future cyber attacks against critical infrastructure. “Attacks are now politically motivated and between two countries rather than directly against the company,” he said.

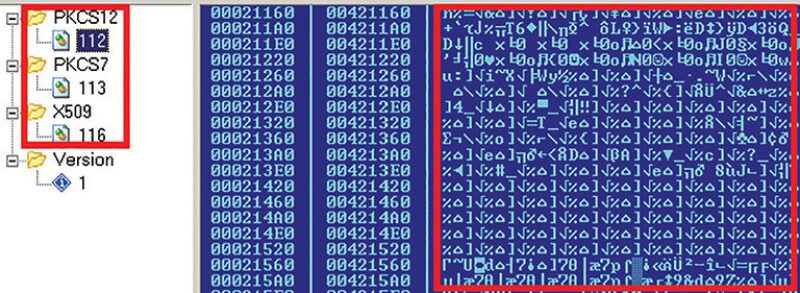

Companies are able to deduce that the cyber espionage is state-sponsored partly because of how the codes are written and partly due to their sophisticated nature that suggest they took a lot of time and resources to create.

The security community has identified several sophisticated cyber espionage campaigns in recent years that have targeted hundreds of oil and gas companies worldwide. The malware involved in these cases have been given names such as EnergeticBear, DragonFly, DUQU, and Flame. Each iteration is more evolved than the next.

To strengthen its defenses, Nguyen noted that BHP Billiton has developed several strategies that include investing in new network monitoring tools and mandatory “cyber safety” training programs for employees—who are often considered a firm’s biggest cyber risk factor.

BHP Billiton has joined efforts started by the American Petroleum Institute and SPE to collaborate with others when sensitive information is involved. The framework is modeled after what the financial and insurance industries have adopted. The company is also sharing threat intelligence information with the US Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Department of Homeland Security. Many other oil companies have taken similar steps to protect their networks.

Many Wake-Up Calls

On its website, ExxonMobil reports, “On average, our cybersecurity screening programs block more than 70 million emails, 140 million internet access attempts, and 150,000 other potentially malicious actions each month.” That amounts to more than 2.5 billion blocked actions a year.

Unfortunately, it only takes one malicious email to get through and there is no shortage of examples of what can happen next. Headlines were made in 2008 when servers at ExxonMobil, BP, Shell, ConocoPhillips, Marathon Oil, and Baker Hughes were accessed by hackers reportedly acting on behalf of China. According to various reports, the hackers accessed seismic data, bid and lease information, and intellectual property that took years to acquire and was worth millions of dollars.

A few years later, Saudi Aramco was hit hard by one of the most infamous malware codes called Shamoon. The 2012 attack infiltrated and deleted data from at least 35,000 computers, estimated to be 75% of the company’s total. Shamoon effectively halted business operations for days.

Weeks later, the same malware infected the IT networks at Qatar’s RasGas. The security community attributed these attacks to actors in Iran. And in 2014, hackers hit at least 250 companies in Norway, including Statoil and about 50 other oil and energy related organizations. That attack is considered the worst of its kind in the nation’s history.

Lessons To Learn

Chris Kubecka, a cybersecurity consultant and researcher who helped lead the recovery efforts of Saudi Aramco’s Shamoon attack, has spent the last few years speaking about what companies should learn from the event.

What has tied together so many of the attacks against the industry, including Shamoon, is the fact that they were initiated when an employee clicked open a malicious email. The tactic is known as spear phishing and increasingly, the spam filters meant to protect against such a threat are being beaten.

Kubecka said hackers have become proficient at testing the limits of the filters and are finding their way past them by customizing emails to meet the intended victim’s personal or business interests, a practice called social engineering.

“Social engineering in and of itself is a really hard thing to combat because the emails are written in such a way that they look real. You want to open that email, or click that link,” she said. “It is a very, very big problem and it amazes me to this day why more companies do not have, at bare minimum, phishing exercises.”

Spear phishing campaigns often use Trojan horse viruses contained in Microsoft Excel or PDF files. One phishing strategy that oil and gas professionals should be particularly aware of involves malicious emails that appear to be sent by a legitimate conference organizer.

Kubecka said oil and gas companies should not only train their employees to be on the lookout for these threats, but teach them to forward suspicious emails to their IT teams so they can be examined rather than just deleting them upon receipt. She also advises oil and gas companies to come up with a playbook to follow when one slips through and they are facing a cyber attack.

“One of the things that completely failed with the attack of Shamoon was that they were not prepared at all—absolutely not prepared,” she said, adding that cyber-related threats need to be treated much in the same way the industry has come to address health and safety matters. Companies are also being warned against letting cybersecurity fall off the radar once they have recovered from a serious episode.

“You might have a lot of focus just after an attack, but a year or two later suddenly it’s just not viewed with the same type of importance anymore,” she said. “The staff that may have been hired on just after the attack starts dwindling in numbers because the perceived necessity is no longer there. Unfortunately, attacks against the industry are increasing every single year.”