The 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris, known as COP21 because it was the 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, marked a turning point for energy and low-carbon domains with the signing of the Paris Agreement. Among its ambitions, the accord elevated carbon capture, use, and storage (CCUS) as a core pathway for decarbonization. Yet a paradox remains since Paris. The COP paradox is that no host nation has had all of the following components in place: a national CCUS law, an operating direct air capture (DAC) plant, and a project nearing CO₂ injection for pure geological storage through the ethanol-to-storage pathway.

By contrast, COP30, set for 10–21 November in Bélem, Brazil, represents a historic first, with Brazil having all three components in place, plus a fourth—a carbon removal pavilion inside the COP framework—formally recognizing carbon removal and associated technologies as viable solutions. This is further bolstered by Brazil’s 1% Clause and funding mechanism (valued at more than $1.55 billion dollars over the past 2 years), which have supported more than 200 CCUS and low-carbon projects from 2017 to 2025 (Fig. 1), driven by oil and gas concessionaires. Notably, COP30 marks the first time in more than a decade that the summit will convene in the Western Hemisphere and the first time it will be hosted in a city within the Amazon region.

Brazil’s 1% Funding Clause and the Global South

As previously covered in the Journal of Petroleum Technology, the 1% mechanism unlocked South America’s first DAC plant, which was visited by the Society for Low Carbon Technologies (SFLCT), a US-founded, globally operating nongovernmental organization (NGO), reinforcing its collaborative role in shaping Brazil’s CCUS law, enacted through the Fuel of the Future program and backed by the presidency. Together, these efforts and others position Brazil as a first-of-a-kind COP host nation.

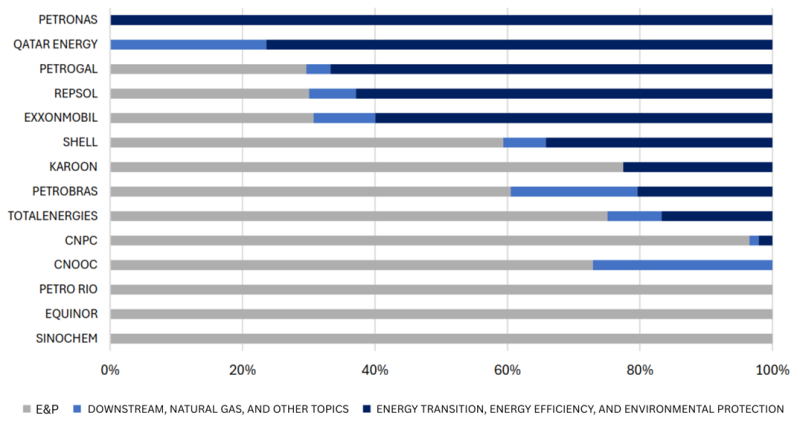

Moreover, Petronas, the Malaysian-owned oil and gas company, set a precedent by dedicating 100% of its 2024 1% contributions from its Brazil operations to energy transition, efficiency, and environmental protection projects, through which approximately $779 million was generated under the 1% Clause in 2024. This complements the state-controlled energy company Petrobras’ historically leading contributor role under Brazil’s funding mandate. In September, Petrobras announced an onshore saline storage pilot scheduled to start operations in 2028 to inject roughly 100,000 tons of CO₂ annually.

This is part of a broader landscape in which Brazil already accounted for 28% of global CO₂ injections in 2024 [principally through offshore enhanced oil recovery (EOR)], underscoring its technical capacity and readiness to pivot toward dedicated storage. Brazil is preparing for not only onshore but also offshore non-EOR injection, a combination no country has yet fully achieved, signaling material progress on both land and sea.

That momentum extended along a South America-to-South Asia arc when the low-carbon NGO met with Petronas in Rio de Janeiro the day after Malaysia codified its own CCUS law in 2025 (Fig. 2). Driving the South Asian front of this arc, SFLCT’s Pakistan chairman, Osama Rizvi, executed the nation’s first low-carbon agreement alongside the author. At COP29, Rizvi met with the World Bank to confront Pakistan’s smog crisis and advance a decarbonization strategy—an institutional thread that COP30 now builds upon. These collaborative milestones underscore the rising influence of the Global South, with Brazil positioned as a fulcrum ahead of COP30.

Brazil’s Strategic and Unique Funding

Keeping with the 1% Clause, this mechanism is administered by Brazil’s regulator, Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis (ANP). It establishes a total investment obligation under which oil and gas concessionaires must allocate annually 1% of gross production revenue—which has generated $1.55 billion dollars over the past 2 years—toward national capacity building and knowledge dissemination through accredited institutions, resulting in technologies such as DAC.

ANP’s 2024 data shows that companies such as Qatar Energy, Petrogal, Repsol, and ExxonMobil each directed more than half of their mandatory investments to energy transition, efficiency, and environmental protection (Fig. 3). This signals a marked shift in capital allocation, underscoring the will and motivation driving Brazil’s leadership in this domain in advance of COP30, with effects poised to reverberate throughout this decade and into the next.

Meanwhile, Petrobras’ $111 billion 2025–29 business plan reinforces Brazil’s decarbonization trajectory, with $16.3 billion allocated to CCUS and other low-carbon initiatives, a 42% increase from prior commitments, including early-stage CCUS hub development. Equally important, ExxonMobil’s presence underscores historical continuity, as it co-developed the world’s first dedicated CCUS project without EOR with Equinor in 1996—a milestone that laid the foundation for today’s global low-carbon ambitions. With more companies channeling over half of their contributions toward energy transition, the remainder of this decade will test the depth of this commitment and determine what low-carbon breakthroughs can be achieved.

A COP30 Nation’s Maneuvering

In addition to managing the 1% Clause, ANP now oversees the CCUS domain. The SFLCT is in direct dialogue with ANP to support Brazil’s regulatory carbon capture advancement. In July, the Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME) mobilized a dedicated CCUS subcommittee under the Fuel of the Future program, directly tied to the CCUS law, anchoring the country’s stance at COP30 and beyond. Notably, SFLCT participates in this subcommittee alongside FS Energia and ANP. As the low-carbon organization noted recently, this unified effort positions Brazil to present at COP30 how low-carbon diplomacy can translate into regulatory clarity, financial innovation, and technical scalability.

The subcommittee’s launch marked a significant step, coming just 1 year after Brazil enacted South America’s first CCUS framework with presidential backing. This momentum aligns with Petrobras’ saline pilot and FS Energia’s leadership of Brazil’s first ethanol-to-sequestration project in São Paulo (slated for near-term deployment), with CO₂ sequestration credits already contracted at $150 per tonne.

The US and Brazil, as the world’s top two ethanol producers, share an evolving ethanol-to-CCUS trajectory. In 2017, Archer Daniels Midland became the first US company to inject non-EOR CO₂ under an EPA Class VI permit. It is therefore unsurprising that the Class VI template has been mirrored in Brazil—applied by FS Energia as publicly demonstrated at a hybrid workshop hosted by MME in July. This serves as a calibrated template to domestic and international market actors, signaling that the ethanol sector offers a ready, reliable, and safe pathway to scale carbon capture domestically while reinforcing Brazil’s sovereign direction.

This pathway reinforces a shared blueprint in which SFLCT holds field-proven institutional experience. That experience is embodied by Zach Liu, an SFLCT advisory member and director of subsurface at Harvestone Low Carbon Partners. Liu helped deliver the first CO₂ sequestration project at a US ethanol facility in 2023 following the Inflation Reduction Act, which catalyzed carbon capture deployment by setting an $85-per-tonne incentive for point-source capture.

Conclusion

Brazil’s unprecedented readiness raises a fundamental question that speaks directly to the COP paradox referenced earlier. The COP paradox is the absence of carbon capture components at the time a nation is hosting COP, such as a dedicated national CCUS law, a CCUS project nearing CO₂ injection, the operation of a DAC plant that is capturing CO₂, and a formal recognition of carbon removal through a dedicated pavilion within the COP framework.

This raises a key question: Should future COP hosts be chosen for milestone performance rather than diplomatic rotation? A new framework, Article CC25: Carbon Capture Readiness (with “25” denoting the year 2025), could emerge to measure CCUS readiness as a benchmark of national low-carbon maturity. After all, the United Nations promotes negative-emission technologies, including CCUS, as an essential pathway to reach the ambitious targets set out by the Paris Agreement.

While not the sole benchmark, such a standard would elevate COP convenings by prioritizing nations actively shaping the path forward rather than those merely pledging action. In this context, Brazil at COP30 stands as the first host nation to break the COP paradox by arriving with all four components in place.