In July 2021, commemorations marked 33 years since the 1988 Piper Alpha tragedy in the UK sector of the North Sea where 167 oilfield workers lost their lives. Without question, the incident was a watershed event for the international oil and gas industry, not simply because of the immediate toll in human lives lost but also in terms of the devasting aftermath endured by countless friends, families, and loved ones whose lives were forever changed. The tragedy also served to illustrate just how poorly the oil and gas industry really understood and managed those operating risks that possessed the potential for catastrophic loss, both in terms of business cost and overall reputational impact.

In the wake of the public enquiry that followed and was chaired by Lord Cullen of Whitekirk, one of the principal recommendations required that the international oil and gas industry do a much better job both in determining its major hazards (i.e., major operating risks) and in creating the necessary operating conditions to demonstrate that such things were being managed well. The objective was to provide tangible assurance that the likelihood of the industry ever incurring such a calamitous event again had been reduced to as low as reasonably practicable.

In taking its responsibilities seriously, the international oil and gas industry responded by raising the profile of the management of health, safety, and the environment (HSE) across the wide spectrum of its global operations. By the mid-1990s, the industry had implemented comprehensive and structured systems of work within the framework of purposely built HSE management systems using templates designed and developed for the industry through the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers (IOGP).

In the 30 years following the tragic events in the North Sea, the international oil and gas industry relentlessly pursued a laser-like focus on the management of HSE, establishing ever-more-ambitious targets to reassure stakeholders that the likelihood of such disasters ever happening again would simply be unthinkable. Indeed, a demonstration of overall performance improvements achieved regarding the management of HSE were regularly volunteered and reported through the IOGP over a period of many years. And, until relatively recently, the culmination of the majority of these seemed to confirm just how much progress the industry had made in addressing the issue, essentially putting the subject of competent HSE management to bed. But on 23 March 2005, following a period of extended plant maintenance, a major explosion occurred at the Texas City Refinery in the US, killing 15 workers and injuring more than 170 others. And on 20 April 2010, the ultradeep Macondo well in the US Gulf of Mexico sustained a well blowout just as drilling operations were beginning to wind down. The resulting explosions and fireballs were of such ferocity that they resulted in 11 fatalities and the total loss of a huge, state-of-the-art, semisubmersible drilling rig. Furthermore, approximately 6 million bbl of crude was released, resulting in the largest oil spill in US recorded history. Finally, what had been considered a potentially very lucrative well for the operator subsequently had to be abandoned.

Although these two infamous events have been well publicized, they are certainly not unique among a seeming catalogue of disasters that served to undermine the reputation of the oil and gas industry. So how is it possible that, in the 30 years since the international oil and gas industry declared a commitment to eradicate the unthinkable, such catastrophic events continued to occur—especially in light of so much evidence being on hand asserting overall HSE performance improvements?

This paper addresses this clear conundrum and submits that there are essentially three principal challenges that lead to such things continuing to occur unless the industry fundamentally changes its ways and begins to chart a very different course regarding HSE and operational risk management.

The three challenges are as follow:

Prioritizing Prevention of Occupational Injuries Over Major Operating Risks—The first challenge is a failure to comprehensively move past a historic focus on occupational injury prevention and systematically measure and manage those operating risks that have the potential for catastrophic loss.

Blaming Front-Line Workers for Human Error vs. a Dysfunctional Operating Culture—When things go wrong, organizations often see failures and unplanned events as a result of one-time isolated occurrences at the worksite (a few rotten apples) rather than leading indicators of wider disconnects within the operating culture, which are likely owned by the top half of the organization.

Flawed Use of Performance Metrics To Gain an Accurate and Reliable Picture of Operations—Using performance metrics that measure the wrong things (i.e., occupational injuries) in the wrong way (backward looking) leads to complacency and a false sense of security vs. measuring the right things (management of major operating risks) in the right way (forward looking). The point being that, even if organizations began to focus more toward the management of major operating risks, until the performance yardstick likewise shifts (from outputs and results to actions and behaviors), they would likely still only know how well they’ve done in the past, not how well they’ll likely do in the future.

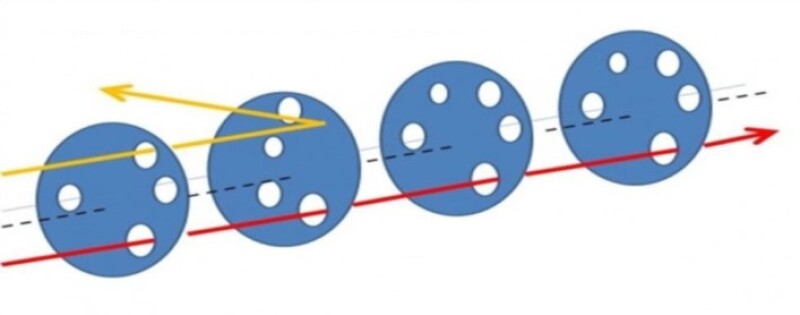

So, not only must the industry begin to fundamentally view the underlying causes of such disasters through a very different lens but, significantly, must begin to look for solutions in places that are sometimes well removed from the worksite and may reside (perhaps with some discomfort) close to the corner office. But one thing that all such disasters within the industry have in common is that, right up until the point where disaster struck, organizations were often oblivious to any early warning signs of catastrophe.