In June, another US supermajor made a big bet on the still-emerging practice of extracting lithium from what some call brine and what those in the oil patch tend to just call produced water.

The investments coming from oil and gas companies mostly hinge on the use of direct lithium extraction (DLE) technologies that capture the precious metal that is suspended in oilfield wastewater.

The latest entrant is Chevron, which now holds 125,000 net acres across Texas and Arkansas atop the Smackover Formation, a reservoir that began its industrial life more than a century ago as an oil field.

Chevron joins ExxonMobil and Equinor in the Smackover, which the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank recently described as “ground zero” in the race to commercialize lithium-laden brine.

ExxonMobil revealed plans more than 2 years ago to produce enough lithium from the Smackover to make the batteries for 1 million electric vehicles by 2030, with first production expected in 2027.

Norway’s Equinor entered the play last year through a joint venture with US-based Standard Lithium. That venture recently drilled its fifth well that averaged 582 mg/L. That is the highest lithium concentration seen on the lease since drilling began. A final investment decision on scaling up commercial production is expected by year-end.

The Dallas Fed, which monitors industrial activity in Texas and surrounding states, has cautioned that the Smackover may be more the exception than the rule when it comes to lithium-rich brines in US oilfield wastewater.

However, that hasn’t slowed interest. Companies are exploring upstream synergies beyond the Smackover which straddles parts of east Texas and southern Arkansas.

One example comes from the Permian Basin, where a Canadian company called LibertyStream (formerly known as Volt Lithium) reported at the start of the year that it achieved up to a 99% lithium recovery rate from a facility capable of processing more than 10,000 B/D of brine.

The same firm announced another successful field trial in July using its DLE system in North Dakota’s Bakken Shale where it achieved an average lithium recovery rate of 96% from oilfield brine at a saltwater disposal facility.

A 2024 paper, SPE 220910, authored by researchers from the petroleum engineering departments at the University of North Dakota and the University of Texas, estimated that with enough capital investment the Bakken could yield up to $1.6 billion annually in lithium from the region’s produced water over the next 40 years.

The potential rise of a new lithium industry in the US isn’t going unnoticed elsewhere.

In fact, some of the forerunners in this space are based in Canada where multiple projects are underway in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

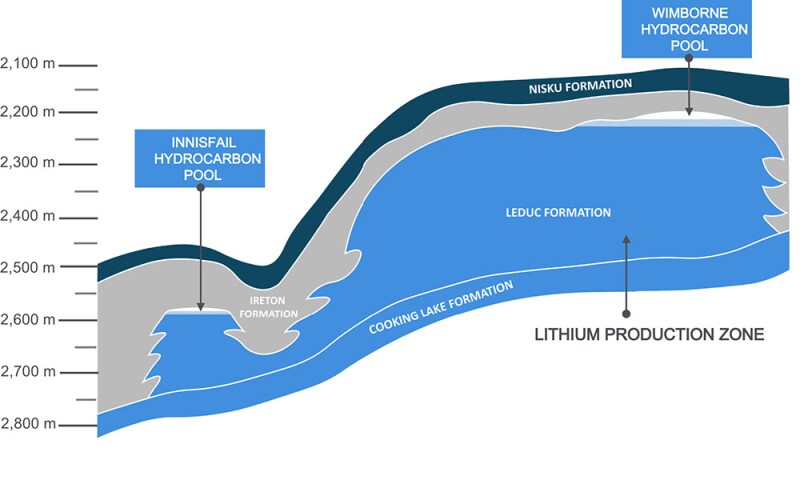

Among them is E3 Lithium, which plans to launch a phased demonstration of a new DLE facility this year and continue into next. The project will start with two new wells but is seeking permits for up to 56 to tap Alberta’s Leduc oil and gas field north of Calgary.

Discovered in 1947, the Leduc field established the region as a major petroleum hub. Today, with an estimated 3 million metric tons (Mt) of lithium reserves, it may be looking at a new future in helping make battery packs.

E3 has highlighted that the reservoir is “well understood” thanks to decades of oil and gas development and that “Alberta’s workforce will require little to no upskilling to transition from oil and gas to lithium.”

In Saudi Arabia, university researchers have joined forces with Saudi Aramco to pilot DLE technology using the oil giant’s various sources of brine. The UAE is following suit with similar early-phase work.

German producer Neptune Energy is also dabbling in this space. In June, it was announced that the German gas producer was partnering with a California-based DLE developer to pull lithium from its produced water in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany.

Every DLE pilot seems to come with claims of a “breakthrough” process. But there are still significant hurdles before oil and gas companies can secure a meaningful foothold in the lithium business.

DLE is one of the most expensive ways to produce lithium, largely due to high energy requirements. The process is also inherently water-intensive, raising concerns about both freshwater use and the reinjection of the stripped brine. Simply sending lithium-free water back into the reservoir can further dilute the remaining resource.

The handful of oil and gas firms entering the lithium space is also doing so at one of the worst times in the sector’s modern history. The International Energy Agency reported that despite global lithium demand surging 30% year-over-year in 2024, supply continues to outpace even that record growth. Since topping more than $74,000/Mt in 2022, lithium prices have plunged by 80%.

Among those issuing a few words of caution is Wood Mackenzie, which has outlined how the lithium map is undergoing tectonic shifts.

In a May 2025 report the energy consultancy projected that Australia’s share of global lithium supply will fall from one-third to one-quarter over the next decade. Outside North America, Africa is expected to play a larger role, while Argentina is poised to overtake Chile as the world’s second‑largest exporter before 2030.

WoodMac also warned that the global lithium market remains “on the brink of a significant supply glut” that may peak in 2027 before switching to a potential shortage sometime next decade.

It’s not just about upstart producers chasing peak prices. China, the lithium industry’s longtime leader, is operating at overcapacity and playing a major role in pushing prices down. Others blamed for the oversupply include producers in Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The downturn in lithium production has already resulted in project delays and cancellations, particularly for those developers that have not locked in investors.

The outlook is further clouded by trade and geopolitical tensions between the US and China, which currently controls about two-thirds of global lithium refining capacity and remains firmly in the driver’s seat when it comes to market dynamics.

Meanwhile, US oil producers looking to enter the market—such as ExxonMobil, with its goal of supplying enough lithium for 1 million battery packs each year—may be in for a dose of supply chain reality. According to WoodMac, the lack of domestic refining infrastructure means that US‑produced lithium must still be shipped to Asia before it can become a battery.

All of this should be a familiar story to the oil and gas companies looking on. Tight supply raises prices, prompting a rush of new projects that are then followed by oversupply and falling margins that squeeze weaker players out.

But just as with past attempts to diversify into other energy sectors, oil companies are not the incumbents. They are just getting in line which for now makes them the underdogs in the great lithium race.

For Further Reading

SPE 220910 Economic Analysis of Lithium and Salts Recoveries From Bakken Formation by M. Jakaria, K. Ling, D. Wang, and J. Crowell, University of North Dakota; and D. Zheng, The University of Texas at Austin.