This is Part 1 of a paper written by the Digital Transformation Subcommittee of SPE’s Digital Energy Technical Sectionon the importance of change management in digital transformation.

Part 2 can be found here.

Abstract

According to a recent study by the consulting group Rystad, $100 billion of value could be saved with automation and digitization in the oil and gas industry. Yes, you heard it right; 10% of the estimated $1 trillion spent annually is the size of the digital transformation prize. “In addition to cost savings,” said Audun Martinsen, Rystad’s head of oilfield services research, “digitalization initiatives can increase productivity by increasing uptime; optimizing reservoir-depletion strategies; improving the health, safety, and environment of workers; and minimizing greenhouse gas emissions—all which have significant value creation.”

Many in the industry have trouble believing opportunities this large. Instead of depending on massive business cases and thinking strategically, they tend to try to subdivide benefits between the different technology investments, think tactically, and end up with much smaller targets. This paper is not intended to get into the difficult question of quantification of value from digital transformation but instead to address the challenges of actually achieving the objectives of each project, of whatever magnitude they may be.

So, how is the industry doing? There is no question that the C Suites and corporate boards of every oil and gas company around the world have already launched their own versions of a digital transformation program; however, many of these companies are now facing a new challenge with the lower-for-longer commodity prices caused by the demand destruction from the global COVID-19 pandemic. Has the digital oil field proven its worth, or is the industry still searching for an effective way to adopt this new way of operating? Maybe the Digital Oil Field 1.0 was a “nice to have,” but, today, the Digital Oil Field 2.0 has become a “must have.”

Introduction

Before recent postponements, technology companies at every industry conference hawked their new emerging technologies, some of which already work while others were not much more than glitzy PowerPoint presentations. Management consultants are, or were, getting hired to staff and direct these digital programs from behind the scenes. Today, they may be the first to get laid off. Chief information officers once again are getting a seat at the table by describing their cloud-first programs and showcasing new analytics teams. Some industry analysts are even forecasting that the current environment of very low oil prices, and the COVID-19 pandemic, will boost digital solutions in the way companies will be working in the future. As we have said, “Houston, we still think the industry has a problem. There is too much D (digital) and too little T (transformation) going on.”

One problem for the industry is that no clear definition has been made for what digital transformation (digital oil field, intelligent energy, or integrated operations) means for the oil and gas industry. One definition—or, often, multiple definitions—is based on operators, asset maturities, segments, defined objectives and work flows, and operation-types perspectives.

The focus often is placed on technologies and discussions about technologies, not only in oil and gas but also in other industries. Technology mostly lies within the comfort zone of most stakeholders in the technical, financial, and managerial disciplines. The new focus, however, is on data science. Subsurface technologies and associated surface technologies are usually missing in action now, as though digital transformation technologies are limited to only data science and advanced analytics. Are the new data scientists pushing the reservoir engineers to the back of the room? Is that a good thing?

For digital-transformation technologies to yield their intended value (Rystad’s $100 billion prize, or whatever your business case is), cross functional collaboration is a necessity. This can be accomplished only by competent change leadership, which is a special domain/role that many managers do not feel comfortable with or are not capable of. According to many case histories, this is the reason (i.e., lack of leadership) many technology-driven projects miss their mark or fail altogether.

Many studies have been conducted on the expected and potential value of digitalization projects, yet no clear approaches, or defined processes, have emerged to estimate their value. Most of the analysis is conducted by outside consulting companies, which are not responsible for sustained performance. We understand that there is not a one-size-fits-all approach for the digital oil field, but determining the business objective of any project before starting is critical. Most digital-transformation projects in oil and gas have sporadic success stories and examples that do not have clear estimates of the exact capital- or operational-expenditure relevance and do not know how to measure the exact returns (i.e., they are full of uncertainties). This may be related very much to the lack of clarity of the original intention and objectives of these projects.

Déjà Vu, All Over Again

It is not the strongest and most intelligent of species that survives but the ones that are most receptive and adaptive to change.

Our industry is not alone in the effective adoption of opportunities presented by digital transformation. Davenport and Redman (2020) wrote, “Success requires bringing together and coordinating a far greater range of effort than most leaders appreciate. A poor showing in any one of four interrelated domains—technology, data, process, or organizational-change capability—can scuttle an otherwise well-conceived transformation. The really important stuff, from creating and communicating a compelling vision, to crafting a plan and adjusting it on the fly, to slogging through the details, is all about people.”

The academic foundation of change management is very well documented, with interesting applications to the oil and gas industry. Choy (2017) wrote, “Change efforts can exert a heavy toll on both human and economic perspectives of the firm. Organizations can reduce and limit these costs by learning from the past experiences and continuously improving future change efforts.”

Despite numerous papers and case studies on the importance of change management in the industry (Anvar et al. 2010; Behounek et al. 2019; Berger and Crompton 2015; Brown 2019; Choy 2017; Coleman and Thomas 2017; Halland et al. 2013; Hayes 2018; Hiatt 2006; Hunter 2015; Keller and Schaninger 2019; Kotter 2012, 1995; Kotter and Cohen 2012; Landsberg 2015; Lencioni and Okabayashi 2008; McChrystal et al. 2015; Ratcliffe and McMillan 2008; Ross et al. 2019; Scott 2019; Sinek 2019), operators still fail to learn from them. We still somehow hope that the next technology solution, or strong business case, will be enough to overcome our inherent weakness in managing the people side of change.

Here are some words of wisdom from SPE paper 112041 (Ratcliffe and McMillan 2008): “Change management means different things to different people. Essentially, change management should be an iterative process that utilizes a set of organization-specific tools and techniques to help an entity and its people transition from a current state to a sustainable desired state. When executed effectively, change management will minimize management risk and maximize return on investment.

“The oil and gas industry’s problem lies in the fact that we struggle to demonstrate conclusive evidence on why these examples of change were successful and what drove that success. Part of the problem is that change management is often delivered in a one-dimensional, linear format that frequently orientates around an individual’s primary skill set. One change manager will churn out newsletters and deliver training, another will place an emphasis on data governance and IT [information technology] transition, while another will focus on stakeholder management or process mapping. The truth is that good change management is all of these things and more. It is how and when we place an emphasis of each of these activities that will dictate the success of the change-management approach. … Change management is a marathon, not a sprint.”

We have seen this problem before. In the early days of the digital oil field in the late 1990s and early 2000s, everyone warned about excessive emphasis on technology and not enough on trusted data and the right conditions for organizational change. The temptation was too strong, and we were too weak and vulnerable. Technology was just too cool not to talk about and play with. Data would not get you the next promotion like a tech invention or even a deployment project would. Project managers left the organizational change management to external consultants or to human resources who could put together really-nice-looking slides for management presentations but not much else; and they did not stay around to help sustain the change.

All the details, models, and experiences that we have been through are definitely a good learning experience, but sustainability continues to elude the industry for the most part. In our experiences, we have even seen early projects slide backward to traditional ways of working once the management focus is taken off the asset team. The following are a few key insights from successful digital-transformation projects:

- Senior leadership and enterprisewide reinforcement, to no surprise, are key.

- We have been at this for more than 2 decades, and, still, most surveys claim less than 20% adoption rates (and even those are at risk at any time).

- Strategic vision and strategy proclamations are still too fragile and easy to change because of priorities and market conditions (such as today’s low oil demand and commodity prices).

- There are probably just a few initiatives/strategic thrusts/values that can withstand company and industry fluctuations. Some examples are

- Safety

- Environmental stewardship

- Lowering operating and capital costs

- Not much else survives the constant industry cycles. Shouldn’t digital transformation rise to that level, as well, particularly in how they can enable the other three?

Core operations practices (e.g., drilling, producing, construction) that are tried and true are easily stopped and started as fluctuations dictate. They are the things companies already know how to do, and the companies can turn the switch off and back on again. New long-term strategic values must continue through the fluctuations of boom-and-bust cycles. Until that happens for digital transformation, the starts and stops will eventually keep it from ever becoming the norm.

Fortunately, digital transformation is designed to improve business performance in both boom and bust times. In boom times, the focus is on work flows that add barrels and drive value. In bust times (down cycles), the focus is on work flows that drive efficiency and cost management. Once established and made part of a new normal, those work flows will add value in both boom and bust cycles.

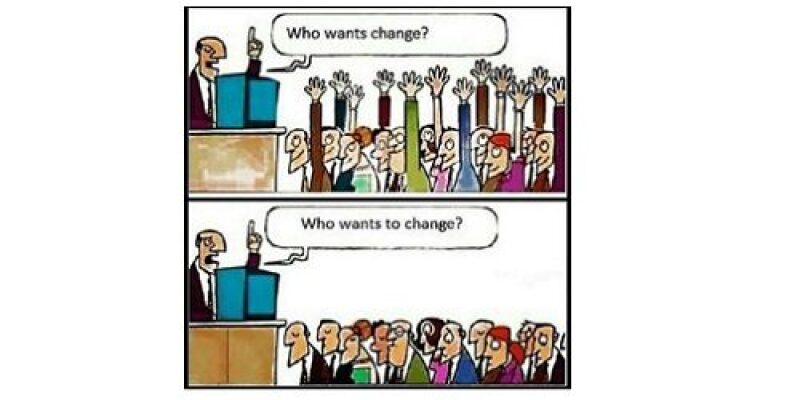

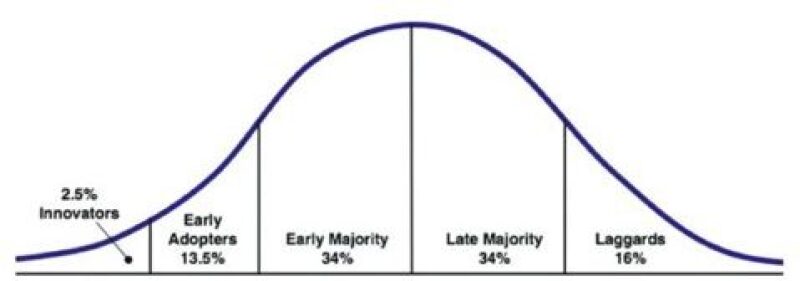

In looking at the innovation adoption curve (Fig. 1), and based on most surveys that have been published, the oil and gas industry is still only in the Innovators and Early Adopters stages at an enterprise level within most companies. Until sustainability becomes a value driven from the top, industry experts just keep saying the same things, albeit in updated fancier ways and with a bit more success in cases that are rarely duplicated. If true transformation can become a value, or at least treated like one, maybe things will change. It has been said that there are two critical drivers for human behavior—fear and greed—and fear trumps greed. Maybe in Digital Oil Field 1.0, we were after greater profits, but, today, in Digital Oil Field 2.0, the objective is survival.

It really seems like this is a repeat of what the industry saw during Digital Oil Field 1.0 as everyone talked about the importance of change management and then spent all of their time and money on technology. In some ways, it might actually be worse this time around; many of today’s executives really do seem to believe that digital transformation is necessary for their future (we are not sure that many of them believed this of the original digital oil field) as the ax has been falling in recent weeks as the oil price drops. We are seeing a desire to protect digital initiatives with smaller, more-focused budgets; however, in many cases, the first thing they cut from their scope is the resource for change management.

Maybe we need a different term here. “Change management” has developed such an underappreciated reputation. Successful change management is hard. It is not just about newsletters, training, or well-designed posters; yet, all too often, that is what people think of when you ask them about change management. Change management, or whatever we call it, is not something that only the official change manager (CM) does. One of the best CMs we have ever worked with talks about everyone needing to be change managers, otherwise the project will fail. People in the team need to value the change-management work and behave accordingly, not just leave everything to the change-management consultant (and then blame them as they walk out the door if things do not work out as planned).

Most people will find referring to change management as a discipline unusual because we often refer to technical disciplines—such as reservoir engineering, petrophysics, and geophysics—as disciplines within the petroleum engineering domain. Change management as a competency, or even discipline, does not get enough respect; the job often can be given to someone with no change-management experience or treated as a spare resource with no current assignment. In a technical industry, it is a softer discipline and not well understood. Would we hand control of our wells to nonpetroleum engineers? Yet we are happy to give change management to anyone around who happens to be available. Having some kind of framework may help to educate people as to the depth and value of effective change management. Technology is the hard job; but change management is the really hard job.

We are not specifically advocating that change management become a technical discipline, like drilling or reservoir, but we want to emphasize the critical importance of change management for the successful adoption of digital-transformation programs. There are already several good SPE papers that address the role of change management in DOF projects by many operators (Anvar et al. 2010; Berger and Crompton 2015; Choy 2017; Halland et al. 2013; Ratcliffe and McMillan 2008; Zeynalli et al. 2019), but the message really has not sunk in. What are we missing?

The choice of the word “discipline” (especially for an SPE audience) is a bit provocative; but that is to get people’s attention to emphasize that one cannot just add a part-time communication specialist to a technology-driven project to successfully achieve digital-transformation objectives. Change management must be a critical aspect of digital-oilfield projects and digital-transformation programs or the results will be much less than a company expects and the sustainability of the initiative will be hard to maintain. Change management must be developed as a leadership competency.

The hardest part of change management is the sustaining phase. Usually, the change-management resources leave the project a few days after go-live (or, in many cases, even before go-live). The Embed and Sustain phase is hardest to get anyone to agree to fund; yet, in many ways, it is the most critical element. Everyone in the industry has seen projects that are working really well at the end of Month 1 but have completely unraveled before the year is out. Why is this? Why can’t we persuade people that investing in change sustainability is necessary?

Big D, Small T

With this big-D/small-T world, once again, the bright, shiny, new technology toys have caught our eye, while the difficult job of really thinking about the way we work and using the technology capabilities as an enabler for redesigning our work process is often left to others, whomever they may be. If things change too fast for people, or companies do not consider the individuals who will be affected, digital transformation can be a recipe for failure and, on a broader scale, even obstinate resistance to the change can develop.

The technology is on everyone’s mind because many companies are trying to sell it and they are very good at getting our attention. No one is trying very hard to sell change management, so there is little marketing for it. This is comparable to cheap medicines (e.g., vitamin D) that are highly effective yet receive no attention because there is little profit. Many digital technologies are adopted and fail, often during the pilot process, because of change management. This represents a significant risk to the technology innovator because, when the technologies are not adopted, the innovator disappears with the invention.

Change management is first and foremost about the human dimension, internal and external stakeholders, and the broader ecosystem within which organizations exist. For change to be sustained, human behaviors must change. Leaders must set clear expectations around behaviors they want to see in action to create and sustain change. Few organizations can realize a profound digital transformation without putting people, not technology, first and getting people on board with the fundamental nature of the proposed change.

A time analysis on digital-transformation projects was conducted by one of this paper’s coauthors, Patrick Bangert, and is displayed in Table 1. It estimates how many man-hours are spent on a typical data-science project in the process industry (including oil and gas, but also chemistry and power) in the various categories of work. This is based on real projects and real man-hour measurements, including man-hours from both the operator and the software vendor; however, it only considers projects that the operator considered successful. It seems to us that the item of Change Management is the watershed between success and failure.

Table 1—Time analysis of digital-transformation projects.

| Total Hours Spent | |

| Change Management | 50% |

| Interfaces / Formats | 25% |

| IT Security / Policy | 15% |

| Reporting | 5% |

| Data Science / ML | 5% |

In that study, Change Management was any activity related to getting people to believe in the methods, the outcome, and the way it was all being done and helping them to change the way they acted based on it. Usually, this required not only discussions and education but also real organizational change—for instance, from reactive to proactive maintenance where an operator needs to start scheduling activities in advance and stock up on spare parts. Project-management activities were subsumed into the topics, so project management related to sorting out IT problems were put into the IT bucket. The scope of the total man-hours was any activity related to the project, no exceptions. The way this was conducted was that a time tool made every person allocate their daily hours to projects and activities.

Other estimates of the amount of effort to put into change-management activities varies from 15 to 20%. We don’t want to exaggerate the budget for change activities; there are different ways to get the job done. The point here is not to dictate to a project how much change resources to budget but to make sure that all the necessary change activities are covered by defined resources before the project gets under way.

Built To Run, not To Change

The easiest way to avoid mistakes is never to make a decision, never to experiment, or never to stray from the corporate compliance manual. Digital-transformation programs require intelligent risk taking; however, all over the industry today, these programs are probably under the budget ax as prices fall. Instead of seeing digital transformation as the way out of this crisis, many companies will see them as an unnecessary investment that can be postponed.

The old saying used to be that no one got fired for buying IBM. To update that saying, you have to say that no one gets fired for buying Microsoft or Amazon. These days, many are diving for the foxholes, trying not to get noticed while budgets are being cut. While innovation feeds off fail-fast/learn-fast work environments, the industry’s response to persistently low commodity prices is to try never to fail at all. When was the last time you saw a group celebrate a failed project because they learned from it or a manager who was promoted after missing her performance targets yet figured out a new way to grow the next year?

Change management, or change readiness, is the means to understand and increase the likelihood of innovation being adopted by stakeholders in any sort of program, be it a major capital facilities project or a digital-transformation project. Most organizations are built to operate during periods of little change and to improve continually through small incremental steps rather than rapid large leaps. Transformation is more than incremental improvements. Frequently, metrics and management bonuses, and even corporate procurement processes, incentivize a message of “stay the course and improve a little.” But is that what we need in today’s economic environment? When your lease-operating expense is $10 below the selling price, is finding a way to save $1 really going to make a difference in the survival of your company? Now is the time to get out of the box and examine every aspect of your business.

Research from Arizona State University (ASU) and the University of Kansas (KU) showed that, even when a compelling innovation solution is implemented today, there is a 70% likelihood that, by the time a fifth project (in a series) is executed, the innovation will have been forgotten and practices will revert to what was done before. The implications of these studies help to explain the slow evolution of digital transformation in the industry over the past several decades.

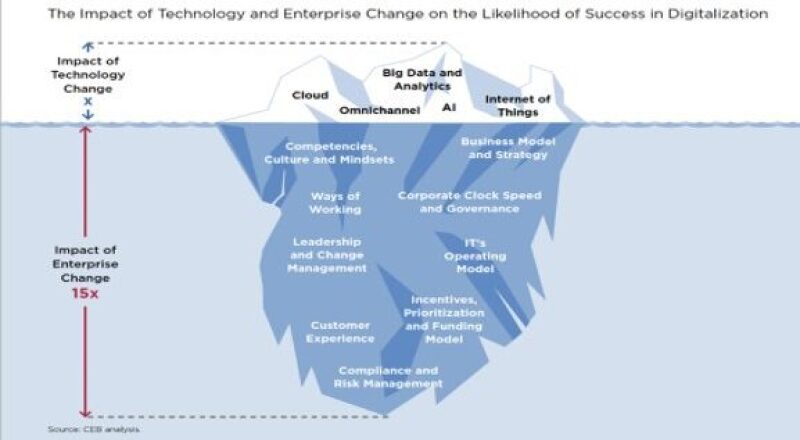

We all know that digital transformation is more than technology (Fig. 2). In their book Designed for Digital (Ross et al. 2019), MIT researchers Jeanne Ross, Cynthia Beath, and Martin Mocker stress the difference between digitization and digital transformation. To quote these authors, “Digitized does not equal digital. Digital technologies can contribute to digitization—applying technologies to optimize business processes and operations. The goal of digitization is operational excellence. Digital technologies are essential to becoming digital—innovating to create customer solutions. The goal of becoming digital is profitable digital offerings.”

The authors point out that most companies are still trying to build an operational backbone and have yet to reach the state of consistently focusing on digital customer or market offerings. This is a confirmation of our view of big D and little T for the oil and gas industry. Most companies in our industry have launched digital programs but only with the objective of digitization, not transformation, despite misusing the term.

We know all about the emerging technologies such as cloud, edge computing, artificial intelligence and machine learning, Internet of things, big-data analytics, blockchain, and more. Few companies really understand the larger challenges of enterprise change that these represent. Successful digital pioneers realize that digital transformation involves taking a serious look at their business model, procurement processes, and enterprise governance and not just the tools they are using. They take a hard look at their leadership responsibilities and focus on change management.

According to Halland et al. (2013), implementing internal changes affecting day-to-day operations is difficult but the digital transformation of the industry that requires implementing change affecting other companies’ processes and deliverables is even harder. The authors of this paper are from Equnior’s early intelligent energy program, and they have identified several key learnings worth repeating.

- Ensure early involvement and close collaboration with suppliers.

- Work on reducing complexity and ambiguity and define deliverables and clear expectations.

- Set ambitions on the basis of supplier competence, experience, and technology.

- Challenge the need for new or customized solutions and plan implementation.

- Prototype and use agile methods in order to reduce risks.

- Define clear roles, responsibilities, and liabilities in the contracts.

- Design compensation formulas and key performance indicators to drive change.

Digital technology enables new ways of working, so even the clock speed of the company (how fast it normally makes decisions) needs to be accelerated. As well as being concerned about the adoption of new technologies, companies are concerned about the digital competencies, culture, and mindset of their organizations. Is their data foundation ready for big data? Are their decision makers ready for data-driven techniques? Or will the entrenched physics wizards (subject-matter experts) shoot down the new machine-learning models that aim to change the proven best practices that have been learned over the decades?

Leading companies are taking a new look at the incentives, job responsibilities, funding, supplier contracts, investment models, and rewards systems in the company as well as the traditional siloed functional structure of their organization. Are employees being paid to continue to work as usual, or is taking a risk and getting outside of the box punished if a mistake is made? Can they be more innovative? Can they emulate the progress of the Silicon Valley startups? Do they even want to? The Silicon Valley mantra of “fail fast” does not translate to the oil industry’s perspective of “be safe and do not fail at all.”

The Digital Transformation subcommittee of SPE’s Digital Energy Technical Section has been interviewing industry leaders on the theme of Digital Transformation (not the technology parts, but the harder parts). We have grouped them into three themes.

- Leadership in the digital era

- Developing the right organizational culture for digital transformation

- Preparing the next generation workforce

We realize that the industry needs more than just a collection of interesting interviews by digital evangelists. The industry needs a playbook to put the needed changes into practice so that the digital technology advances can be adopted more easily. There exists the potential to truly transform the oil and gas industry if executed effectively. Several management consultants have their own commercial approaches to change management, and they are valuable when tried; however, the authors would like to see an open template or body of knowledge more widely adopted. There are too many headwinds right now not to try to share best practices.

The interviews serve as one of the building blocks for the change-as-a-competency framework. The words of those who have lived the life, fought both winning and losing battles, and learned from losing are both inspiration and insightful.

Leadership in the Digital Age

First, it will take strategic leadership for digital transformation to matter, not the kind of prudent and competent operations management that encourages and expects small incremental progress in reducing operations and capital costs. Employees watch the behavior of management very closely. When executives disappear behind closed doors, rumors start to fly. In some cases, fear can be a motivator for change but only if the fear is felt by the whole organization, not when a reorganization program starts by dividing those you want to keep from those you chose to leave behind. Given this atmosphere, even some of the best performers will start to think about leaving. The company is left without key expertise, experience, and future leaders.

The influence of leaders with vision, experience, and authority on the progress and success of any transformation endeavors cannot be underestimated. These leaders work for fundamental changes, not superficial adjustments. They strive for enterprise gain, not personal promotions. They are the ones who not only introduce changes as concepts, but they are the ones who also make these changes happen. They serve as the model for the behaviors they expect to see in their organizations. In many examples, change management extends beyond the boundaries of a single organization because it requires very close collaboration with supply-chain partners and other stakeholders who share similar issues and objectives. The importance of change champions in the organization cannot be understated, either.

Change management is of critical importance in project management also in other industries, such as the construction industry. Construction Industries Institute and Fiatech are organized research units in the Cockrell School of Engineering at The University of Texas at Austin. They both share the mission to improve the capital projects industry dramatically with innovative thinking and collaborative approaches to research and development. In January 2018, these two institutions joined to form one initiative. According to research by Fiatech, there are four key leadership attributes for successful change management (Hunter 2015): strategic vision, expertise, alignment, and pathfinders.

Key Leadership Attributes

Strategic Vision. This establishes achievable objectives for organizational change. Research by ASU and KU mentioned previously show that organizations that have a long-term strategic vision for change encounter six times less resistance than those that implement change from top down or implement forced, rapid change. The research goes on to show that, even when an innovation provides significant productivity gains, more than 90% of engineering and construction organizations fail to sustain long-term adoption. Fortunately, research also shows proven strategies exist for achieving long-term adoption.

Expertise. This must be recognized from all organizational levels touched by the innovation. It is important to engage personnel who understand operational context in their areas of responsibilities. They are ideally positioned to understand and embrace innovation and often have ideas for how to optimize adoption. Equally important is that soliciting their participation creates self-accountability. When personnel know they have been heard and their thoughts have been incorporated into the organizational-change effort, they take ownership and will support the change more enthusiastically. When they are denied an active participation role, personnel will inevitably wonder, “What’s in it for me?” and leadership may face a lack of sufficient buy-in across their organization, which will cause the innovation to fail.

Alignment. This is the people side of change, which is more critical to adoption and sustainability than the technical aspects. Change-readiness leaders must align their personnel for success. Research shows that only 16% of industry personnel can be classified as innovators or early adopters. They are more open and enthusiastic about change opportunities. Change readiness leaders should develop and implement diagnostic tools to assess change-readiness capacity at the individual level and to identify the innovator and early adopter. Identifying these individuals enables leaders to engage them early in the change effort as champions and advocates (change agents), which lays the foundation for early successes to mitigate skepticism and build momentum for the change to propagate throughout the organization.

Pathfinders. These are enthusiastic change agents. They guide the organization during innovation-adoption efforts by ensuring the change vision is communicated in an accurate and understandable form. Research shows pathfinders create a fourfold increase in the change readiness of an organization. Pathfinders are most effective when they have direct involvement at the operational level of the organization. In fact, research shows that change readiness is increased sevenfold when properly trained pathfinders are active within the operational levels. A critical leadership action is to find and develop these pathfinders who will provide in-the-trenches leadership from initial implementation through to sustained long-term innovation adoption.

The following Industry Talk interviews are first-hand accounts of the experiences of change leaders who have lived the key lessons expressed in this paper:

Greta Lydecker, general manager, Chevron, North Sea Business Unit

Shaharuddin Hamid Mustapha, head of integrated operations, Center of Excellence, Petronas

Leslie Malone, formerly area production manager, Sanchez Energy

Bart Stafford, senior operations specialist, Epsis

Developing the Right Culture for Digital Transformation

Remember that everyone does not change at the same pace, so your change-management program cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach. Let’s get back to Fiatech’s recommendations concerning advancement attributes: situational awareness, transparency, foundation and sustainment, and positive accountability.

Situational Awareness. This is the motivator that stimulates and maintains behavior change. Organizations achieve situational awareness through change-readiness benchmarks. These benchmarks provide ongoing visibility and the impetus for innovation by identifying sources of inefficiency and successes through simple, understandable performance metrics. Research shows that change-ready benchmarks must combine core operational outcomes (related to cost, schedule, and satisfaction) and be linked directly to individual personnel and project team success measurements. Change-readiness benchmarks can be consolidated to provide a complete performance map of entire groups, programs, and organizations.

Transparency. This creates an environment where personnel are better able to understand and optimize their work products and flows. Transparency provides a live feedback loop that triggers natural and spontaneous behavior change at the individual level. This is accomplished by providing structured communications of change-readiness benchmarks to individual personnel in near real-time. Management and specific managers often are loath to establish metrics to avoid being seen as failing. However, when clear metrics and expectation are quantified and communicated, better alignment can be achieved. Once individual change occurs on a widespread basis, the culture of the entire organization can evolve rapidly.

Foundation and Sustainment. These provide the underpinning for both innovation and long-term adoption. Research shows that organizations can increase change readiness by eightfold with proper and targeted change-related training. Be sure not to fall into the trap of thinking that training is all you need. Many leaders think that change management is a synonym for training; just train and go. Human resources departments have helped cultivate this mentality.

Executives must know how to communicate the change vision and align their organizations for success. Operation managers need to understand how to act as successful in-the-trenches change agents. They must take steps continually to ensure the participation and engagement of front-line personnel. To accomplish this, they must solicit feedback, gain buy-in, and build the new skill sets needed to change operations traditions. They must define expected behaviors, continually model them, and recognize people widely within all levels of their organizations who demonstrate these behaviors. Organizational change is not a discrete, one-time event; rather, it is continuous education throughout all stakeholders and is critical to achieve sustained innovation adoption.

Positive Accountability. This is the monitoring, identifying, and celebrating of organizational-transformation wins throughout the innovation-adoption process. Leaders cannot take a carrot-and-stick approach during organizational change; instead, they must emphasize positive and strategic personal development. Continually highlighting specific change-related achievements engages personnel reflections on positive progress, such as a successful project, as isolated areas of improvement or enthusiastic personnel actions. Additionally, conducting periodic workshops to reflect on progress and discuss current challenges helps to build and maintain personnel skill sets.

The following Industry Talk interviews are first-hand accounts of the experiences of change leaders who have lived the key lessons expressed in this paper:

Helen Gilman, vice president, technologies, Wipro

Michelle Pfleuger, manager of corporate digital innovation and acceleration, Chevron

References

Anvar, A., McClelland, C.P., and Mueller, K. 2010. The Role of Human Factors Integration and Change Management Coaching in Integrating Multidisciplinary Teams Working in Collaborative Work Environments. SPE Intelligent Energy Conference and Exhibition, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 23–25 March. SPE 128616. http://dx.doi.org/10.2118/128616-MS.

Behounek, M., Millican, B., Nelson, B., et. al. 2019. Change Management Challenges Deploying a Rig-Based Drilling Advisory System. SPE/IADC International Drilling Conference and Exhibition, The Hague, Netherlands, 5–7 March. SPE 194184. http://dx.doi.org/10.2118/194184-MS.

Berger, T., and Crompton, J. 2015. Change Management in the Digital Oil Field: We Know We Need It, but Where’s the Roadmap? SPE Digital Energy Conference and Exhibition, The Woodlands, Texas, USA, 3–5 March. SPE 173423. http://dx.doi.org/10.2118/173423-MS.

Brown, B. 2019. Dare To Lead: Brave Work, Tough Conversations, Whole Hearts, first edition. New York: Random House.

Choy, A. 2017. Change Management and Its Impact on Organizational Performance: Empirical Evidence From an Oil and Gas Firm. SPE Asia Pacific Health, Safety, Security, Environment and Social Responsibility Conference, Kuala Lumpur, 4–6 April. SPE 185222. http://dx.doi.org/10.2118/185222-MS.

Coleman, S., and Thomas, B. 2017. Organizational Change Explained: Case Studies on Transformational Change in Organizations. New York: Kogan Page.

Davenport, T.H., and Redman, T.C. 2020. Digital Transformation Comes Down to Talent in Four Key Areas; Harvard Business Review, 21 May 2020, https://hbr.org/2020/05/digital-transformation-comes-down-to-talent-in-4-key-areas (accessed 2 June 2020).

Edwards, A.R., and Gordon, B. 2015. Using Unmanned Principles and Integrated Operations to Enable Operational Efficiency and Reduce Capital and Operational Expenditures. SPE Middle East Intelligent Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition, Abu Dhabi, 15–16 September. SPE 176813. http://dx.doi.org/10.2118/176813-MS.

Halland, T., Jensen, L.K., Eike, M., and Solnordal, D. 2013. Implementing Intelligent Energy—Change Management Experiences and Recommendations. SPE Middle East Intelligent Energy Conference and Exhibition, Manama, Bahrain, 28–30 October. SPE 167451. http://dx.doi.org/10.2118/167451-MS.

Hayes, J. 2018. The Theory and Practice of Change Management. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hiatt, J. M. 2006. Adkar: A Model for Change in Business, Government, and Our Community. Loveland, Colorado: Prosci Learning Center.

Hunter, R. 2015. Change Readiness: Adopting Innovation for the Long Haul. Engineering News Record. www.enr.com/articles/9047-change-readiness-adopting-innovation-for-the-long-haul (accessed 2 June 2020).

Keller, S., and Schaninger, B. 2019. Beyond Performance 2.0: A Proven Approach to Leading Large-Scale Change. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.

Kotter, J.P. 1995. Leading Change: Why Transformational Efforts Fail. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press.

Kotter, J.P. 2012. Leading Change. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press.

Kotter, J.P., and Cohen, D.S. 2012. The Heart of Change: Real-Life Stories of How People Change Their Organizations. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press.

Landsberg, M. 2015. The Tao of Coaching: Boost Your Effectiveness at Work by Inspiring and Developing Those Around You. London: Profile Books.

Lencioni, P., and Okabayashi, K. 2008. The Five Dysfunctions of a Team: An Illustrated Leadership Fable. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.

McChrystal, G.S., Silverman, D., and Collins, T. 2015. Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World. London: Portfolio Penguin.

Prosci 2020. What Is Change Management? Prosci. www.prosci.com/resources/articles/what-is-change-management (accessed 2 June 2020).

Ratcliffe, F.H., and McMillan, G. 2008. Change Management Made Easy: A Practical Approach to Change Management for Digital Oilfield Programs. SPE Intelligent Energy Conference and Exhibition, Amsterdam, 25–27 February. SPE 112041. http://dx.doi.org/10.2118/112041-MS.

Ross, J.W., Beath, C.M., and Mocker, M. 2019. Designed for Digital: How To Architect Your Business for Sustained Success. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Scott, K.M. 2019. Radical Candor: How To Be a Kickass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity. New York: St. Martins Press.

Sinek, S. 2019. Start With Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone To Take Action. London: Portfolio Penguin.

Zeynalli, A., Butdayev, R., and Salmanov, V. 2019. Digital Transformation in Oil and Gas Industry. SPE Annual Caspian Technical Conference. Baku, Azerbaijan, 16–18 October. SPE 198337. http://dx.doi.org/10.2118/198337-MS.

The Digital Transformation Subcommittee of SPE’s Digital Energy Technical Section is

Jim Crompton, Colorado School of Mines

Patrick Bangert, Algorithmica

Melanie Bladow, Tern Consulting

Tony Edwards, StepChange Global

Helen Gilman, Wipro

Mike Hauser

Marise Mikulis, EnergyInnova

Steve Smart, Accenture