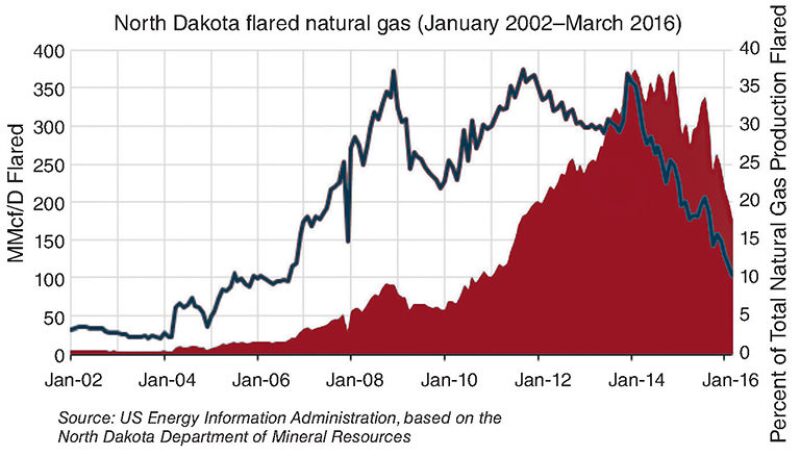

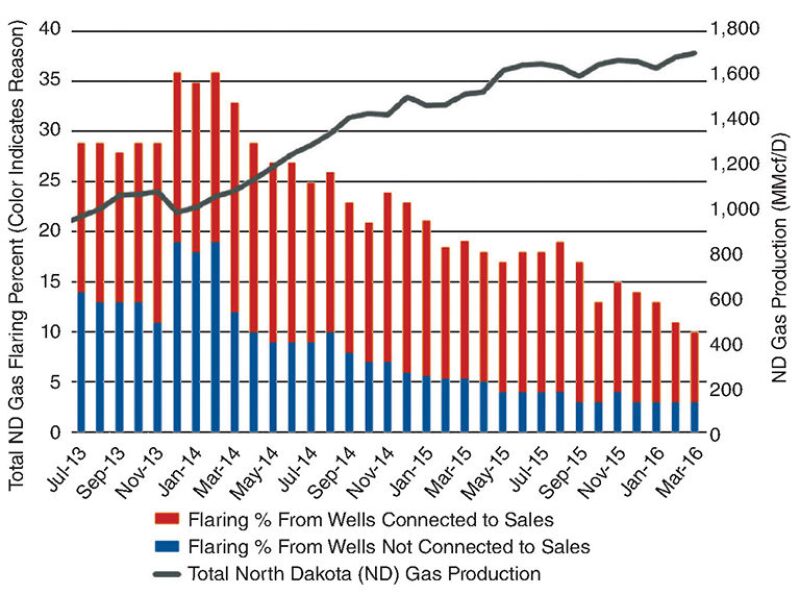

Natural gas flared in the Bakken has abruptly declined this year, reaching 8% in April, a striking change from the days when more than one-third of the gas from the oil-rich formation was burned.

“In 2014, flared volumes in the state reached 0.35 Bcf/D, equal to almost half of total volumes that were either flared or vented in the United States,” according to a report by the US Energy Information Administration (EIA).

The percentage of gas flared in April was half of what it was at the end of last year, and the volume is the lowest since 2011, according to totals reported by the state.

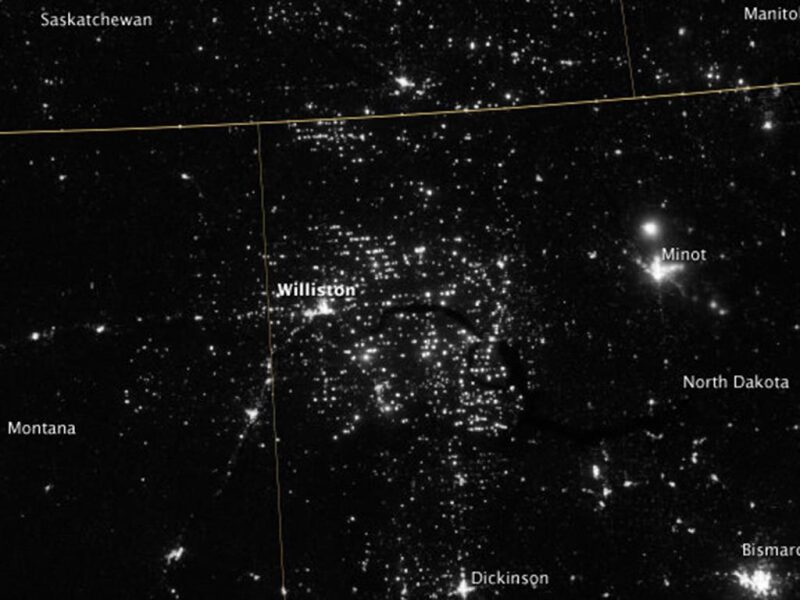

During the Bakken boom in 2014, nighttime pictures from space served as a sign of the times, showing the light from the many flares in the sparsely populated state that otherwise would look mostly dark. While lights are still visible, they are not as bright.

The EIA reported flaring in the state “has declined sharply since 2014,” based on numbers from the North Dakota Industrial Commission’s Department of Mineral Resources.

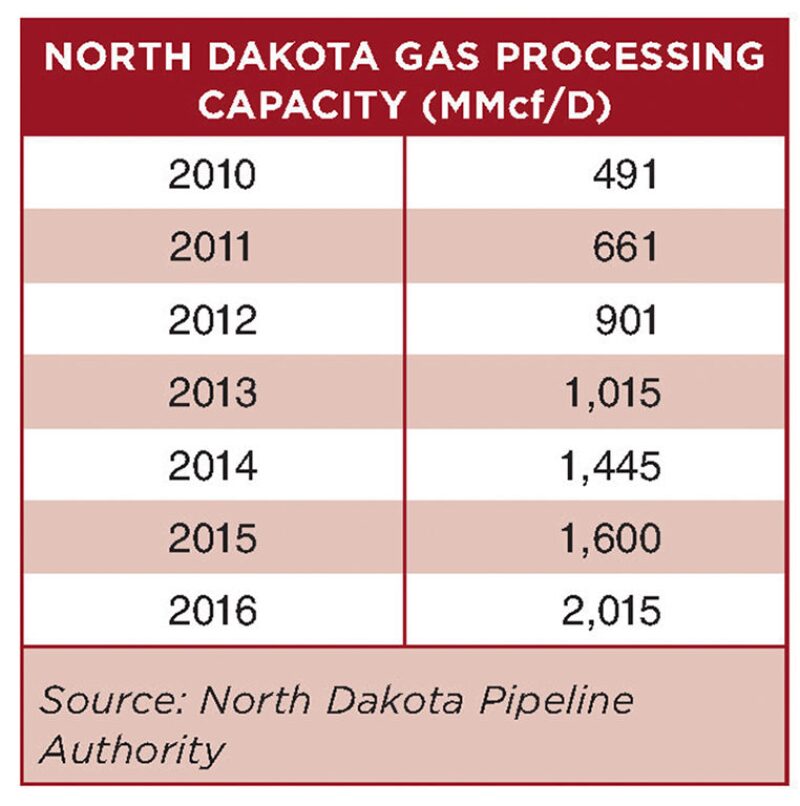

The volume of gas flared is down (see figure above) because more is flowing to market via the state’s expanded network of pipeline and processing facilities. The amount burned looks even smaller as a percentage because the total amount of gas produced has been rising in North Dakota, which set a record for output in March.

The accelerated rate of decline was a bit of a surprise. Last fall, North Dakota regulators stretched out the timetable for a reduction in flaring to 10% of the total gas production by 2020, after the industry asked for more time to deal with issues slowing the expansion of pipelines and processing facilities.

North Dakota officials are wary about declaring victory. “In the near term we expect to have a high level of gas capture in North Dakota,” said Justin J. Kringstad, director of the North Dakota Pipeline Authority, who closely follows the business. “But over the long term it is something we are continuing to look at.”

Gas-Rich Formation

When it comes to gas production, the Bakken is in some ways a special case among oil-producing formations. For one, the formation also produces a lot of gas—2–3 Mcf of gas for every barrel of oil—and the rich mixture requires processing to remove liquids, such as propane, before it can be shipped via gas pipeline.

While oil and gas production in North Dakota goes back more than 50 years, the transportation and processing capacity needed for those aging fields was far short of what is needed for the Bakken, which covers much of the western part of the state. The transportation challenges were compounded by its location far from major oil and gas markets.

Oil production rose so fast that large-scale shipping using rail cars was required, and still is, but that is not an option for gas.

North Dakota’s reaction was also unique. It set targets for flaring reduction based on frequently updated public data. “North Dakota was the first state to require gas capture plans for spacing hearings and drilling permits,” said Lynn Helms, director of the North Dakota Department of Mineral Resources, adding, “This allows for midstream and gas processing investors to plan correct pipeline size and location based on development drilling plans.”

Two factors that allowed North Dakota to catch up with gas production—slow drilling allows pipelines and processing to catch up—should apply in other states where the backlog was never as large to begin with. But flaring numbers are hard to come by.

In south Texas, gas flaring in the Eagle Ford was getting critical attention. A 2014 story in the San Antonio Express-News concluded that from 2009 until mid-2014, enough gas was burned to have supplied the city of 1.4 million with all the fuel needed for heating and cooking for 4 years.

But drilling there has dropped sharply, with 34 rigs working in mid-June in three south Texas districts that contain the formation (tracked by Baker Hughes), compared to 142 working in 2014. Gas demand in the formation adjoining the border with Mexico has surged in recent years as gas export capacity flowing south has doubled since 2012.

Keeping up with the changes in the amount of gas burned is challenging because few states track it. North Dakota, US offshore operators, and the state of Texas report on flaring, but the lag time for the Texas monthly report recently exceeded a year, said Neal Davis, an industry economist for the EIA, whose responsibilities include the tracking of flaring.

The next national estimate of gas venting and flaring will be in the annual EIA report on natural gas to be released in the fall.

Catching Up

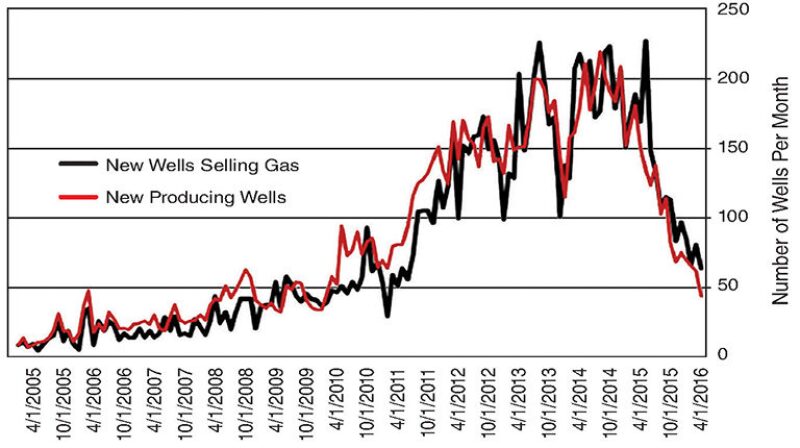

The plunge in oil prices rapidly reduced the number of drilling rigs working and wells coming on line at a time when pipeline and processing capacity was growing in North Dakota.

As a result, more wells were hooked up to sales lines—in 2015, 4% of the gas produced was flared because wells were not connected to sales lines—and pipelines were better equipped to handle the gas produced—14% of the flaring was due to a lack of capacity. When the pipes were installed, no one could anticipate how the technology would push up production.

“The pipes put in place were not adequate to meet production requirements,” Kringstad said. Gathering lines designed to accommodate one or two wells might now be serving a pad with 16 wells, each producing more gas than the wells the line was designed to handle.

Long-term construction programs begun by midstream companies have added compressors to push more gas through lines, and gas processing plants to remove liquids such as propane and ethane from the exceptionally rich gas.

“It is not something that could be done overnight,” he said. So far, two new processing plants have been added (this year), and two more are expected to come on line during the third quarter of the year.

The drilling slowdown means the average age of the wells in North Dakota is rising, increasing the likelihood the well is selling what it produces. The EIA report said that during the first 6 months of production, the average percentage of gas flared by a typical well in North Dakota is twice the volume flared by older wells.

North Dakota regulations penalize those who fail to address flaring. After a well has been in operation for 1 year, an operator must pay all the taxes and royalties due on all gas produced, even if it is burned. Flaring declines accelerated this year, with the amount dropping to the lowest level since June, 2011, according to state records.

When oil prices rise high enough to justify completing wells, it will test the capacity of the system. But while the benchmark price recently approached around USD 50/bbl, sparking talk of more drilling in Texas and Oklahoma, North Dakota’s remote location and limited oil pipeline capacity depressed the price of high-quality crude sold there to about USD 38/bbl. The state is working now to narrow that gap by adding pipeline capacity, reducing its dependence on high-cost rail shipments.