When Shell slashed its dividend by 66% on 30 April, it not only sent shock waves through financial and business communities throughout the world, it “tore up the industry’s financial playbook,” according to Laura Hurst at Bloomberg. Amid the chaos and damage churned up by the pandemic, what had long been unthinkable—the world’s largest supermajors ceasing to defend their dividends at almost any cost, given the importance of payouts to North American investors—suddenly became fact. The last time Shell had slashed its dividend coincided with World War II, nearly 80 years ago. Equinor also cut its dividend, and ExxonMobil froze its dividend for the first time in 13 years.

Asked whether the long-held strategy of sacred payouts to shareholders was sustainable in the current situation, Shell Chief Executive Officer Ben van Beurden said, “I would say, no.”

“I think a crisis like this has the potential to catalyze society into a different way of thinking,” van Beurden said.

Total has now joined Shell and other European counterparts, BP and Repsol, in setting ambitious climate targets. Despite a drop in profits as the coronavirus has decimated fuel demand, the French company committed to eliminating most of its carbon emissions by 2050 and to investing more in clean energy. Its shares rose 6%, to $34.90, immediately following its announcement—almost three times the gain in France’s benchmark index.

Announcements like these from Shell and Total reflect the ongoing pressure on oil giants from investors and society to tackle long-term environmental challenges.

“I think we’re in the midst of a paradigm shift in terms of how we think about the scope of investing, which in turn is related to a shift in thinking about the purpose of the public company from one of shareholder primacy and short-term profit maximization to one that focuses on delivering what is often referred to as long-term sustainable value to all stakeholders,” said Jon Hale, head of sustainability research at the Morningstar global financial services firm. Stakeholders include customers, employees, and communities up and down the supply chain in which the company operates, and the planet itself, as well as shareholders.

For many years, it was universally understood that institutional investors’ main objective, and the investee company’s main obligation, was to maximize short-term returns for shareholders, and that factors such as social and environmental impacts required a tradeoff on the investor’s part. More recently, with the rise of the “responsible investment” movement, ESG criteria not only allow investors to put their money where their values are, but also play a practical role in evaluating a company’s ability to manage risk.

One thing that has moved the needle in the direction of what Hale refers to as “sustainability thinking” is the development and collection of sophisticated and large amounts of data about companies’ performance, including ESG performance. “So, it’s really gotten more focused on materiality,” Hale said. “And it’s not so much based on values anymore for investors as it is on really wanting to drive the long-term value of an investment.”

“The bigger your base of sustainable investors, the more leeway corporate management has to shift in this direction,” Hale said.

ESG: How Did We Get Here?

ESG represents the integration of human values into the financial value of investments. The term was coined in 2005 with the launch of the UN-backed Principles of Responsible Investing (PRI), which are based on the notion that environmental, social, and governance issues such as climate change, human rights, and executive pay can affect the performance of investment portfolios and should be considered alongside more traditional financial factors in making investment decisions to ensure a more sustainable global financial system.

ESG environmental criteria consider how a company performs as a steward of nature. Social criteria examine how it manages relationships with employees, suppliers, customers, and the communities where it operates. Governance deals with leadership, executive pay, audits, internal controls, and shareholder rights.

“Beyond conservational, ethical, and social objectives, the investment rationale for higher-ESG-rated companies presumes that such companies are better prepared to deal with anticipated as well as unexpected large-scale risks that the future may bring. The coronavirus crisis fast-forwarded us into the future, and the world has to deal with a disruption of vast proportions. One could argue that proper governance should have some impact on how well a company might cope with the disruptions … ,” said Bloomberg.

Young investors are particularly active in the responsible investing movement, which gained traction after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill and Volkswagen’s emissions scandal, among others, devastated the involved companies’ stock prices, resulted in billions of dollars in associated losses, and eroded confidence and trust in those companies’ ability to operate responsibly. Now, with consideration of ESG seen increasingly as part of a company’s fiduciary duty to all its stakeholders in the US, EU, and other markets, brokerage firms and mutual fund companies offer exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and other financial products that follow ESG criteria. Financial services companies such as JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, and Goldman Sachs track performance and publish annual reports that extensively review their ESG approaches and the bottom-line results.

According to many analysts, ESG criteria explain much of the wariness in E&P-related investments over the last 2 or 3 years. Even before coronavirus concerns escalated, most energy stocks declined as the supply-demand imbalance increased; greenhouse emissions grew, along with concerns about climate change; shale oil and associated gas production continued without producing positive cash flow; and concerns mounted over gender diversity and executive pay.

Energy Transition: The Journey Ahead

Energy transition in today’s world refers to the global shift away from finite, primarily fossil-based energy toward renewable energy sources, which have become a powerful and cost-effective source of electricity. Costs of both solar and wind have fallen so drastically that in some parts of the US, and in the UK and Europe, wind power has become cheaper than traditional fossil-based energy resources. Although federal subsidies for wind and solar energy are set to expire, the demand for renewable energy, driven primarily by corporations’ large-scale renewable energy purchases, will likely remain high. As costs continue to fall and these sources become mainstream, the renewable energy sector will keep growing and solidify as a strong investment opportunity. For these reasons, energy transition is central to ESG investing, and it will continue to increase in importance as investors prioritize ESG factors.

The Emissions Story

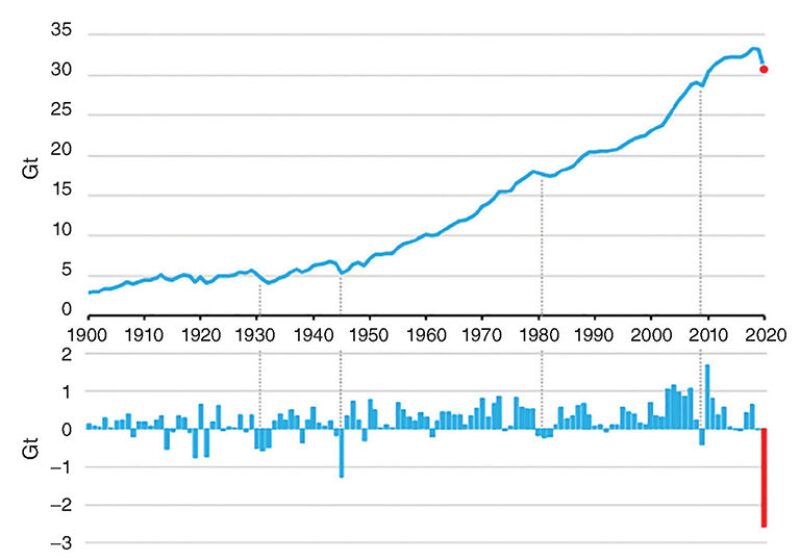

The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that global CO2 emissions will fall in 2020 by 8%—or, almost 2.6 gigatonnes (Gt)—the largest decline ever. The decline is six times larger than the previous record reduction of 0.4 Gt in 2009 and twice as large as the combined total of all previous reductions since the end of World War II.

Comparing the 2008 collapse with the current one, McKinsey & Company said the extra spending on clean energy following the 2008 crisis contributed positively to the broader recovery. Government money also helped spur the development of key low-carbon technologies.

From an emissions perspective, however, the recovery from 2008 was energy- and carbon-intensive. Although CO2 emissions declined by 400 metric tons (mt) in 2009, they rebounded to 7 billion mt in 2010—the sharpest upswing in history.

The current economic crisis is more severe than in 2008 to 2009, and the decarbonization challenge is more urgent. Additionally, energy technologies have advanced, and some vital components for building a clean energy future are now more mature and ready to scale up.

Teleworking, greater reliance on digital channels, and other adjustments that may continue long after lockdowns have ended may help companies “build back better” after the crisis, reducing demand and emissions. Repatriating supply chains could reduce some scope 3 emissions. And, markets may better price-in risks (particularly climate risk) as the result of greater appreciation for physical and systemic dislocations. This would create the potential for additional near-term business model disruptions and broader transition risks, but also offer greater incentives for accelerated change.

Additionally, public appreciation for scientific expertise in addressing systemic issues may increase. And there may also be a greater appetite for the preventive and coordinating role of governments in tackling such risks.

Conversely energy transition could be delayed by low prices for high-carbon emitters that increase their use; struggles by governments and populations to integrate climate priorities with pressing economic needs in a recovery; delayed capital allocation caused by decreased wealth; and exacerbation of national rivalries if zero-sum-game mentality prevails following the crisis.

According to the IEA, based on previous crises, the rebound in emissions may be larger than the decline—unless the wave of investment to restart the economy is dedicated to a cleaner and more resilient energy infrastructure (Fig. 1).

What Steps E&P Companies Are Taking

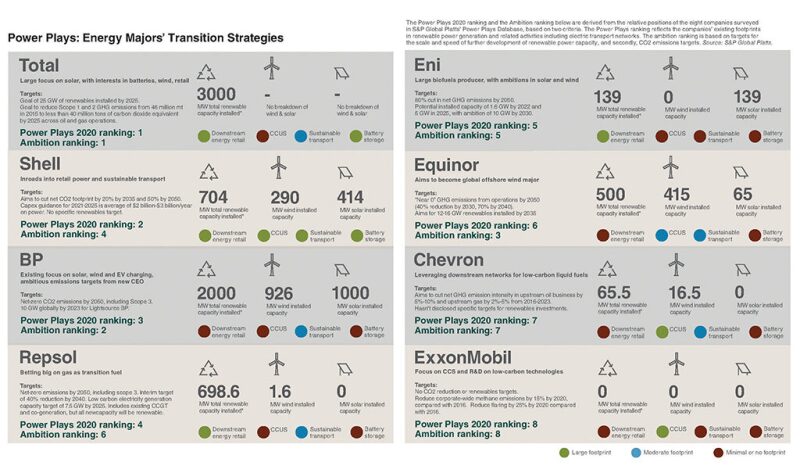

S&P Global Platts summarized and ranked eight major oil and gas companies’ transition strategies in its Power Plays 2020 ranking (Fig. 2). The ranking is derived from the relative positions of the companies surveyed in the S&P Global Platt’s Power Plays database, based on two criteria. The ranking reflects the companies’ existing footprints in renewable power generation and related activities, including electric transport networks. The ambition ranking is based on targets for the scale and speed of further development of renewable power capacity and CO2 emissions targets.

Total has invested billions of dollars in recent years in batteries, wind, and solar energy, and is now catching up with European rivals such as Shell, BP, and Repsol, which have already set ambitious climate targets. Total, which currently allocates more than 10% of its capital expenditure to low-carbon electricity, will increase that share to 20% by 2030 or sooner. The company had stakes in 3 gigawatts (GW) of renewable-power capacity at the end of 2019 and is targeting 25 GW by 2025. It recently took stakes in giant solar projects in India and Qatar, and has expanded clean power in Spain, the UK, and France.

Shell’s New Energies Business is active in over 60 projects across the world, as of February 2020. This includes renewables such as wind and solar, new mobility options such as electric-vehicle (EV) charging and hydrogen, and an interconnected power business that will provide electricity to millions of homes, companies, and businesses.

Chief Climate Change Adviser David Hone said Shell has spent more than 20 years looking at the climate and how the company would manage the inevitable transition to address climate change. He sees the company’s net carbon footprint ambition as a transition pathway and a metric that allows all Shell stakeholders to view and understand its progress.

“The net carbon footprint is built around Shell’s ambition and also around the way society moves,” said Hone. “As we supply more zero-emission energy products, our net carbon footprint will fall. But we can’t do it all on our own. Where we continue to supply products that result in emissions at the point of use, those emissions must be managed by the people who use them. But Shell will also be involved on a sector-by-sector basis with our customers.”

“If society can move even more rapidly toward a 1.5°C goal, Shell will do so as well,” Hone said. “That will mean that shorter-term incremental targets for our net carbon footprint, and their link to pay for our senior executives, will need to become more ambitious. We want to be seen as a company that transitions with the energy mix, and the energy mix of the company is more aligned with the energy mix of the world,” he said.

“Some hydrocarbons will continue to be used for the remainder of this century and into the next, because they are very useful in many realms,” said Hone, “but managing emissions within that time frame is possible and necessary.”

BP has adopted ten aims to help the company and the world reach net zero. Among these, in addition to cutting the carbon intensity of the products it sells, reducing methane, and increasing the proportion of investment into non-oil and gas, is stopping corporate reputation advertising and redirecting those resources to active advocacy for progressive climate policies.

The company owns the UK’s largest EV charging network and is an equal partner in the world’s largest sugarcane biothermal producer. It also has built a significant wind business in the US. BP’s carbon capture, use, and storage (CCUS) projects include the first large-scale gas-fired power station with embedded carbon capture technology, now in the planning phase in Teesside in the UK; and a solar joint venture through Lightsource BP for the first solar-powered steel mill, in Colorado.

Chevron Technology Ventures (CTV) launched its Future Energy Fund—the sixth fund in its 20-plus year history—in 2018, with a $100-million initial commitment to lower oil and gas emissions and invest in technologies in low-carbon value chains. The portfolio includes startup companies in EV-charging autonomous vehicles, battery management for energy storage, energy-efficient electric motors, carbon capture, and energy optimization software.

Barbara Burger, CTV’s president, said, “We did something we don’t normally do with our investments. We invested in three CCUS companies. Two are at the point source, and one is direct air capture.”

Svante, formerly Inventys Thermal Technologies, developed a solid adsorbent technology that lowers the cost and increases the efficiency of capturing CO2 from industrial flue-gas streams. Carbon Clean Solutions Ltd. (CCSL) is developing a proprietary, intensified solvent-based technology to lower the cost of capturing CO2 from flue-gas streams. Carbon Engineering advances direct air capture technology to remove CO2 directly from the atmosphere for use in its recipe for lower-carbon gasoline, diesel, and jet fuels, without requiring engine redesign or retrofit.

“CCUS is absolutely essential across the industrial sector for energy transition and meeting climate goals,” Burger said, “but one of the biggest technology challenges is the cost.

“The possibility of lowering the cost of the process is important to more widespread adoption of the technology,” she continued. “We are excited about working with these companies to scale their technologies.”

According to Burger, CTV’s investment in breakthrough technologies and commitment to helping them reach scale embodies one of the three pillars of Chevron’s approach to energy transition. The other two are cost-efficiently lowering the company’s carbon intensity and increasing the use of renewable energy in the company’s businesses.

ExxonMobil is field testing eight emerging methane-detection technologies across 1,000 sites in Texas and New Mexico. All technologies and deployment methods will be used to detect leaks and identify potential solutions that can be shared with other oil and gas operators, to enable action at a greater scale across the industry.