A recent investment into a Calgary-based technology developer aims to solidify the future of computer vision as a widely used digital tool in the oil and gas sector.

Computer vision is a branch of artificial intelligence (AI) that uses machine learning to quickly process and analyze visual data from photos or video. The technology has a number of popular consumer-targeted applications, such as Apple’s Face ID, but it is earlier days for more complex tasks such as the fine-tuning of driverless cars.

Founded in 2011, Osprey Informatics is one of the companies leading the charge to show how computer vision is ready to be put to work in the oil field. The firm has developed software that uses internet-connected cameras to monitor wellsites and field facilities for methane leaks or potential trespassers.

In December, the firm raised $3.75 million Canadian dollars ($2.83 million USD) to expand its operations, which will include the opening of a new office in Houston. Shell’s venture unit led the investment with two Calgary-based venture groups that have ties to the upstream sector, InterGen Capital and Evok Innovations.

The idea behind Osprey came when one of its founders worked as an intern for an oil company in Alberta and realized how many of the long-distance trips to the field could have been done remotely through video. Cameras by themselves would not equal efficient inspections, so the young company turned to advanced programing that could sift through the videos autonomously.

“Obviously there have been cameras at industrial sites for a very long time, but they typically have not had a lot of operational utility,” said Jeremy Bernard, the firm’s chief operating officer, pointing out that industrial surveillance footage is rarely reviewed in real time. “What computer vision allows you to do is look for specific activities or objects of interest to end users at a very accurate level, and then tailor the information for the user to make it actionable.”

As Osprey’s computer programs recognize certain events, field managers are sent short clips via email or text message, which means they know what is going on before someone is dispatched for a site visit. More than 30 upstream and midstream companies in the US and Canada are subscribed to this software-as-a-service, which it says is reducing physical inspections for some users by 50%.

Michael Crothers, the president and country chair of Shell’s Canadian division, highlighted in a release that the industry is undergoing “rapid change” because of artificial intelligence and machine learning. “We see Osprey’s technology as a core component of this digital transformation, with proven operational benefits and promising methane detection potential,” he said.

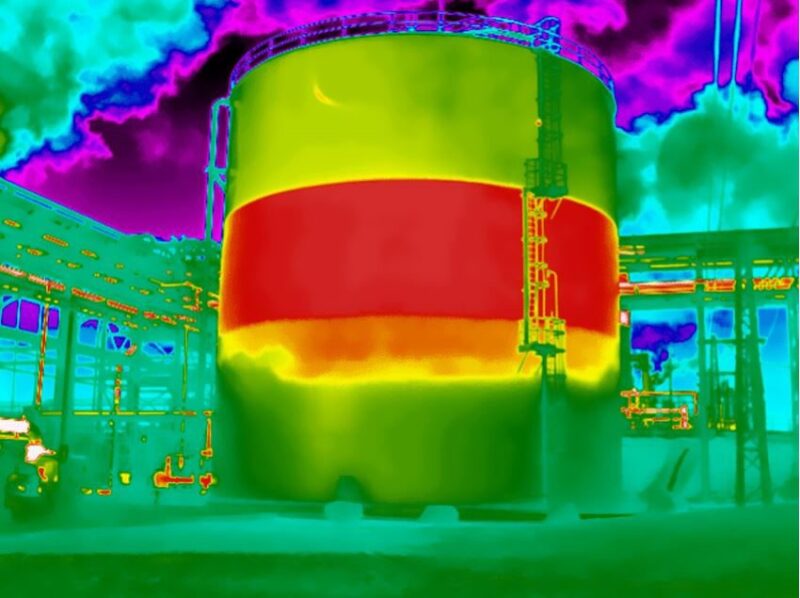

When connected to cameras using thermal imaging, the software sends out alerts as methane releases are seen emitting from storage tanks. Work is under way to extend this capability to much lower-volume fugitive emissions from wellheads or compressor stations.

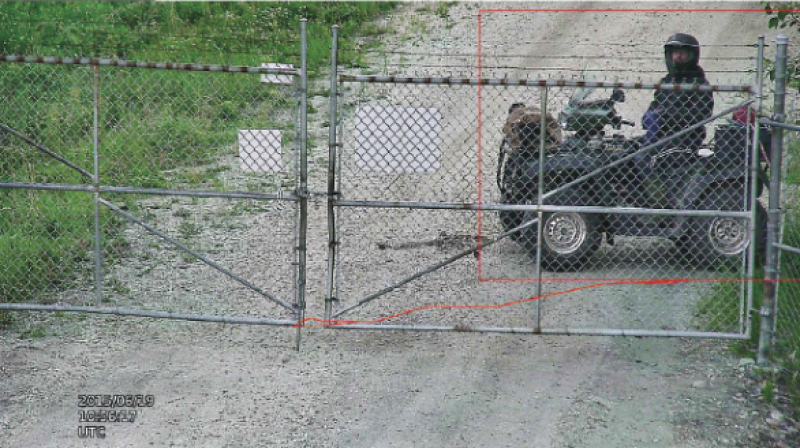

As a security application, notices are sent out if a truck or an individual shows up to a wellsite after normal hours. To reduce false alarms, the program has been trained to distinguish between vehicles and animals.

Just like the “smart” Wi-Fi-enabled security cameras seeing rapid uptake in the consumer market (e.g., Amazon’s Ring), the software’s management-by-exception feature means no one is needed to sit in front of a screen to catch one of these events.

The thin red box highlights where a computer program detects potentially suspicious activity. The advanced software can be used on existing camera networks to add a layer of automation for security operations at facilities and well locations.

Aiding Automation

Prior to the latest round of funding, Shell already had been using the computer vision service in its Canadian operations, along with Calgary-based Cenovus, a heavy oil producer that is aligned with Evok. Other current subscribers include XTO Energy and Chevron.

Osprey says a number of its clients turned to the technology after crude oil prices collapsed beginning in 2014. The layoffs that came with the downturn continue to challenge oil and producers years later with field staffing needs, positioning computer vision as a way to adapt.

“There is absolutely a mandate across the industry for automation and to manage more assets with fewer people,” said Bernard, adding that operators “want to be prepared for the next time there is a big price crash.”

To advance the role computer vision will play in the drive toward increased automation, Osprey plans to release several new applications over the next year. One ongoing trial involves monitoring the movement of a rod lift unit to notify an operator when the pump’s cadence falls outside of pre-set baselines.

For now, the software can be integrated with a well pad’s SCADA, or supervisory control and data acquisition system. This gives field operators a quick way to confirm operating data with a visual check.

Last year Osprey partnered with Zedi Solutions, a cloud-based SCADA provider, so that alerts issued by the platform are fed into the SCADA interface and eliminate the need for field operations teams to view multiple screens.

Tracking the movement, run or stop, of an artificial lift unit helps add a visual layer to the operational data streaming in from the field.

The Start Of A Trend?

Several other firms have joined Osprey Informatics in the effort to find where computer vision best fits within the oil industry. There efforts suggest a wide range of applications exist for this newly introduced technology.

Saudi Aramco has recently explored the technology for automated corrosion inspections (SPE 190036).

Shell has also partnered with Microsoft to develop computer vision technology to identify safety incidents as they happen, including whether customers are trying to light cigarettes at its retail stations.

In one of the most similar examples to Osprey Informatics, Houston-based Marathon Oil is working with a startup called Pixel Velocity to monitor its Eagle Ford Shale assets with cloud-connected video cameras.

Raleigh, North Carolina-based CoVar Applied Technologies is yet another newcomer with a background in the defense sector using computer vision to analyze pipe handling systems and shale shakers on drilling rigs.