Without better political, regulatory, and fiscal alignment, the UK is unlikely to achieve a “just and fair” energy transition by 2030.

The Delivering Our Energy Future: Pathways to a “Just and Fair” Transition report, released this month by the Energy Transition Institute at Robert Gordon University (RGU), concluded there are limited paths to reaching UK’s net zero by 2050 and Scotland’s net zero by 2045 commitments.

In March, the UK government announced it was halfway to its net-zero goals, having cut emissions by 53% between 1990 and 2023.

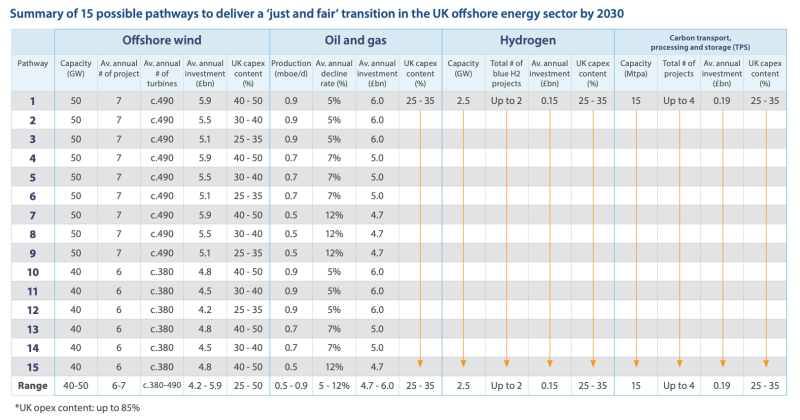

The RGU study analyzed more than 6,560 avenues the UK offshore energy industry could follow through 2030 and determined UK and Scottish political decisions, rather than energy market economics, will determine the size of the workforce and supply chain. The study analyzed the ambition of the target by sector by 2030 and how much of that ambition is executed in the UK by a UK supply chain and workforce.

Of the analyzed possibilities, the report concluded fewer than 15, or <0.3%, meet the just and fair transition principles, and that all such scenarios would require billions of pounds of additional investment in the next 6 years.

The United Nations defines a just and fair transition as “ensuring that no one is left behind or pushed behind in the transition to low-carbon and environmentally sustainable economies and societies.”

For the UK, the study linked the definition to jobs, investments, and economic contributions. In the UK, a fair and just transition would sustain UK offshore energy industry jobs to 2023 levels or better, sustain UK offshore energy supply chain investments at 2023 levels or better, and sustain UK offshore energy workforce economic contribution at 2023 levels or better.

The three main factors, according to the report, that will affect the transition are the rate of decline in oil and gas production, the extent of investment in renewable energy sources, and the degree of UK content associated with this investment.

Paul de Leeuw, director of the Energy Transition Institute, said in a release that accelerating the repurposing of the North Sea as a world-class, multienergy basin would ensure the sector can power the country for decades.

But that won’t be easy.

“The prize for the UK to get this right is enormous. But to deliver this requires action and urgency, which means faster planning and consenting and access to the grid,” he said. “We also need more-flexible electricity-pricing mechanisms to avoid project delays or cancellation and a proactive focus on building UK content so we can design, manufacture, install, commission, and operate some of the critical new infrastructure required.”

Large Investment

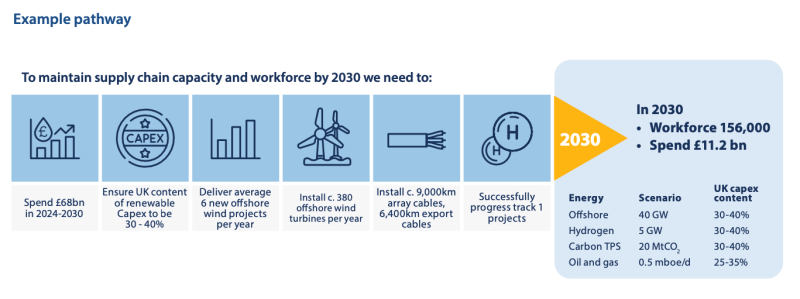

De Leeuw said the UK offshore energy sector needs to spend up to £200 billion over the remainder of this decade across offshore wind, hydrogen, carbon capture and storage (CCS), and oil and gas projects to enable a fair and just transition.

According to the report, more than 90% of the UK offshore energy spend between 2024 and 2030 is expected to be on oil, gas, and wind activities, with the remaining 10% forecast for hydrogen and CCUS activities. Of the projected spend, about 50%, or £100 billion, is still subject to approval by operators, the report noted.

The region must also maintain world-class skills and capabilities, he said.

“If the UK is unable to deliver close to 40 GW (from 15 GW at the end of 2023) of installed offshore wind capacity and UK content ambitions for the new activities by 2030, it is unlikely to retain the offshore energy workforce without additional activities,” he said.

The report concluded that ongoing political uncertainty, a volatile fiscal regime, slower-than-required progress in the renewables sector, cost pressures, and an accelerated decline of the UK oil and gas sector are undermining investor confidence, which could result in a 15% decline of the UK offshore energy workforce to 130,000 by 2030, from 154,000 in 2023.

Scotland is likely to be disproportionately affected, as about 1 in 30 of the working population in Scotland is employed in or supporting the offshore energy industry, compared with 1 in 120 across the UK, according to the report.

While stakeholders tend to agree on the need for a just transition, de Leeuw said a more “agile and joined-up approach” is required to enable the country to secure its energy ambitions while addressing the cost-of-living crisis, managing energy security, and delivering on the net-zero agenda.