Across the US, the number of college students pursuing petroleum engineering degrees has been dropping, leaving a significant shortfall between projected openings and graduating engineers.

Recruiting students into oil and gas is essential, and everyone in the industry can play a role in that, Jennifer Miskimins, department chair for petroleum engineering at Colorado School of Mines and 2026 SPE president, said during a lunch at SPE’s Artificial Lift Conference and Exhibition on 22 August.

She said it’s important not to underestimate the impact even a brief conversation can have about someone’s impression of the industry. One such topic could focus on the standard of living that is possible in the US due to the country’s energy security and contrast that with energy poverty in other parts of the world.

Cyclical Industry, Cyclical Enrollment

“We're an up and down industry. It's frustrating sometimes,” she said.

And those ups and downs aren’t only reflected in quarterly earnings reports.

Large numbers of enrollments into petroleum departments are invariably followed by drops in enrollments, she said. For example, 2017 saw the largest number of petroleum engineering bachelor’s of science degrees awarded.

“2017 was not a great year to be in petroleum engineering, or at least to graduate and be looking for a job in that particular area,” she said.

Fewer people entered petroleum engineering programs.

“Price goes up, enrollment goes up. Price goes down, enrollment goes down,” Miskimins said.

And petroleum engineering departments don’t change as rapidly as prices do; there’s a lag time, she said.

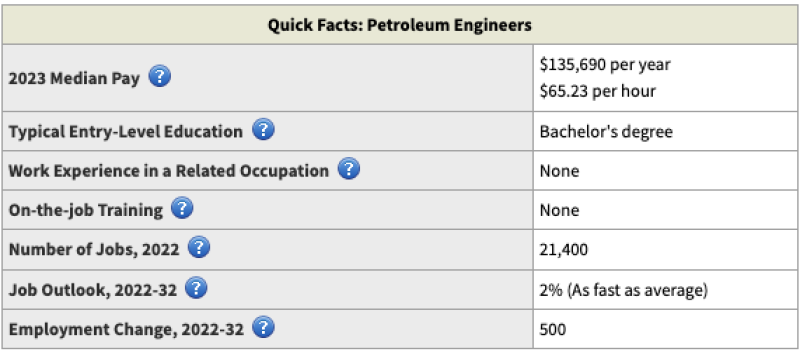

Based on the US Bureau of Labor Statistics’ forecast that petroleum engineer demand would grow at about 2% per year from 2022 through 2032, that means there will be roughly 1,200 openings in the US per year.

“We’ll probably graduate 600 petroleum engineers next May, so we are graduating literally about 50% of what the US Bureau of Labor says we might need,” she said.

At the same time, seasoned professionals are leaving the industry and not returning, she said. That leaves the industry scrambling to make up for the shortfall and finding new ways to draw future students into the industry.

But oil and gas is not the only industry struggling to find interested students.

“We are not alone in this. This is a problem that any subsurface degree is having at this point in time. Geology is having problems with it. Geophysics is having problems with it. Mining is in worse shape than we are,” she said. “It's really a problem of anything below ground; ‘it's old, it's dirty.’ Don't want to do it. They want to go to the moon. They want to go to Mars.”

Changing Programs

One of the main approaches the oil and gas industry has taken to fill the shortfall is hiring engineers from other disciplines and helping them learn the ins and outs of petroleum.

At the college level, some departments are re-evaluating curriculum, she said, with some adding more topics and others considering a name change.

Emphasizing the skills and knowledge of petroleum engineering students as having broad applications could also be helpful, she said.

“You're going to have really, really good subsurface skills. You can work in petroleum, and by far the majority of our students are still going to work in traditional petroleum engineering, but if you have an interest in CCS or geothermal, these are still the same skills. Whether you go into PE (petroleum engineering) or you go into geology or geophysics, these are the same skills that are needed,” she said. “We're not a pigeonholed engineering discipline. It's actually incredibly broad as far as how much you would want to broaden your skills, broaden your interests.”

Miskimins said some students are graduating with degrees in other disciplines but then picking up minors in petroleum engineering.

Reputation Problem

The industry’s reputation isn’t all that stellar outside the industry. As a result, people may not want their loved ones to enter it.

“Parents, family, friends have great influence. I talk to many of my students, even the juniors and seniors, and they tell me they still have friends that question their choice about why they're majoring in petroleum. There's peer pressure. There's a lot of peer pressure out there,” Miskimins said.

The frequency of this has prompted many petroleum engineering schools to educate their own students on how to have conversations with their peers about why they’re pursuing their degree in petroleum engineering and the contributions the industry is making to the world, she said.

Another hurdle that must be overcome in recruiting into the industry is that “they've been told for 18-plus years that there's no future in the industry, that oil and gas is going away, that we're bad,” Miskimins said. “They don't understand where that electricity comes from.”

Aside from not understanding where electricity comes from, they often don’t understand that all energy sources have pros and cons, she said.

“Potential students are inundated with negative images of our industry. We can't change what they hear, but we need to find a way to address that with them in a way that they see as truth, that we're not just greenwashing things for them,” she said.

She said it’s important to acknowledge that the industry is not without its problems.

“Our industry does not have a flawless background. We do not have a flawless history,” she said, but it’s important to let them know that they can be part of the solution because many incoming students want to make a difference and be part of the solution.

The 20/60/20 Approach

Aside from the opportunity to be part of the solution, the salary, opportunity for international travel, and the technology being used in the industry are potential draws for students, she said.

When it comes to feelings about the industry, Miskimins said she divides people into three segments. One segment believes the industry does good work, one doesn’t, and the remainder are undecided, she said.

“There's 20% that are very open to hearing about what we do, and they are not only open, but they're already probably pretty convinced that petroleum is a good thing. We need it. Our industry is good. Let's go with it,” she said. “You’ve got the other 20% on the other side of the spectrum. You're not going to probably ever win them over, and honestly, sometimes it's just a waste of energy, time, and incredible frustration.”

She said it’s that 60% in between who might be won over. They don't usually know what petroleum engineering is or what the petroleum industry is all about and are willing to learn about it, she said.

“Those are the people that we will start to win over,” she said. “And you know what? Even if they don't go into our industry, they might become advocates for our industry.”