One of geothermal energy’s key advantages is that it’s always on.

But making money selling power increasingly requires being able to react to shifts in electric prices by adjusting production up and down.

The fact this is a concern now is an indication of the ambition of a new generation of companies that have shown it is possible to use horizontal drilling and fracturing to build subsurface heat exchangers to harvest large amounts of geothermal energy.

The geologic potential is huge—there are a lot of places with hot rock at a drillable depth.

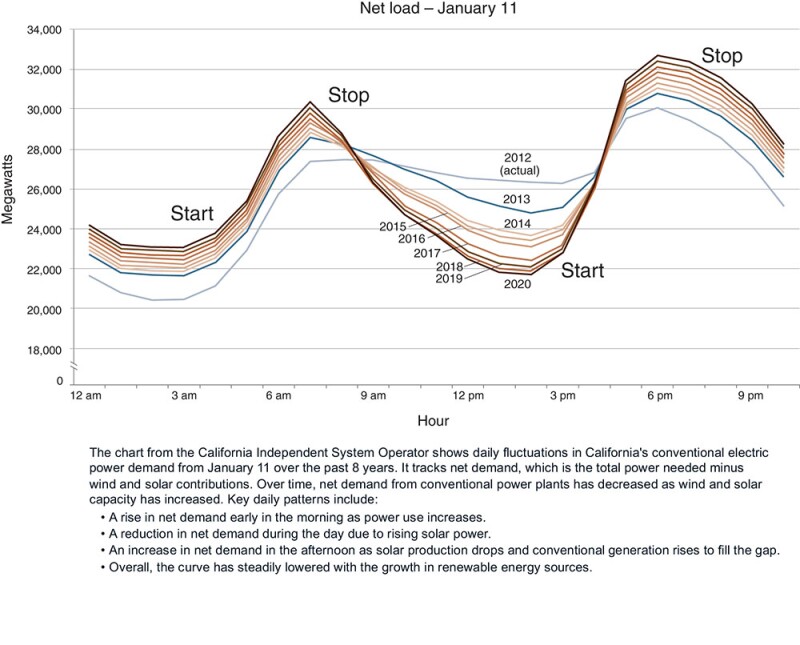

But monetizing that potential will require grabbing a sizeable share of the market in big states such as California and Texas where the price of electricity can sink toward zero when sunny conditions allow maximum solar power production, and then rebound as the sun sets.

This is a pressing concern for Houston-based Fervo Energy because it is one of the first firms in a small pack of innovators to reach the point where it is building a large scale power plant using this emerging technology.

Unlike wind and solar, it can deliver power on demand, similar to coal, gas, and nuclear-powered plants that supply baseload power to the electric market.

Fervo’s founders play up its ability to deliver power on demand, but they resist the label baseload power provider because, as Jack Norbeck, chief technology officer and cofounder of Fervo, said, “In the future, baseload power will be a thing of the past.”

Baseload power plants are not yet an endangered species. There are still large, mostly old fossil-fueled plants providing baseload power that are still around because they were paid for long ago. However, their numbers are declining as they wear out and are hit with demands for costly emission reductions.

The initial sales by Fervo’s Cape Station project in Utah will provide baseload power to southern California power suppliers, complying with a unique California rule that requires them to source low-carbon power supplies that are available 24/7.

But for new geothermal companies to sell enough power to become significant players in US power markets, they will need to provide what the electricity business describes as “more flexible, dispatchable power.”

Big baseload plants ruled the power universe back when regulators set rates high enough to maintain a sizable surplus of generating capacity—ensuring the lights stayed on.

Now, in markets such as Texas and California, power pricing rises and falls based on supply and demand, with selling at all times sometimes resulting in very low payments during peak production periods for solar and wind.

This is particularly true during seasons where days tend to be sunny and windy with moderate temperatures.

“If you are consuming electricity, particularly in the spring and fall, it is an extremely clean grid you are pulling from,” said Christian Gradl, vice president of operations for Fervo during a panel at this year’s Offshore Technology Conference.

Everybody’s Doing It

So Fervo, and everyone else in the electric power business, needs to adapt.

As the influence of renewables grows, new gas-fired generating capacity is projected to rise by only 2.5 GW this year—the lowest rate in 25 years, according to a recent report from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Nearly 80% of those new gas plants will be single-cycle designs which cost less and can react faster to price moves than combined cycle units, which are more energy efficient and cleaner burning.

At the top of the growth chart is solar. Developers are expected to add more than 36 GW of new “utility-scale electric capacity” in 2024, according to the EIA report. More than half of that increase is concentrated in three states: Texas (35%), California (10%), and Florida (6%).

The second-largest growth category is battery storage, which is expected to increase by more than 14 GW, with 82% of that growth occurring in Texas and California. Battery buyers are generally power suppliers using energy storage to shift power sales to times when prices are higher.

The rapid growth in battery storage is supported by hefty US government funding for research and new manufacturing capacity. The research programs support work on longer-lasting batteries as well as lower-cost alternatives to lithium-ion designs.

One sign of the times was Halliburton’s recent announcement that it had added a battery storage startup, Adena Power, to its new technology incubator. The company says its sodium-based battery, which is about the size of a cargo container, will cost 30% less than lithium-ion batteries and can store power for up to 12 hours.

For companies like Fervo working on new geothermal technology, flexible delivery is doubly important at this early stage of commercial development because it allows the company to grab sales at good prices, while it works to lower its cost per kilowatt and find new buyers.

This was a key recommendation in a report done for Fervo by researchers at Princeton University.

“The primary conclusion of this work is that flexible operation represents a viable pathway to large-scale deployment of enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) in future electricity systems,” the paper in Nature Energy said.

Fervo responded by adapting its system to allow it to vary output, an innovation it calls FervoFlex.

“That strategy for us will become ultra-important as the amount of renewable concentration rises in and around the western US. As renewables penetration goes up, the value of more flexible dispatch rises,” Norbeck said.

Adding a Battery

FervoFlex requires changing the analogy used to explain how the company’s technology works.

Rather than steadily pumping the maximum amount of water through the system, like a waterflood, this adds the option of using pressure pumping to build downhole pressure which becomes energy storage that can be released later.

The method takes advantage of the ability of fractures to store energy by expanding when downhole pressure rises as more water is injected than is produced.

There are limits. The companies adopting this approach do not want to re-fracture the reservoir or damage fractured flow paths.

Fervo does this by adjusting the inflow and outflow of water, making it possible to also adjust power generation up and down.

That combination of water heating and energy storage is also a feature of a fractured geothermal system developed by another Houston‑based firm.

However, Sage Geosystems’ approach to fractured geothermal is sufficiently different to warrant a distinct name. Sage refers to its method as the Geopressured Geothermal System (GGS), while Fervo’s technology is called an Enhanced Geothermal System (EGS).

Sage injects water into individually fractured wells and adjusts energy output by controlling their flowback rate. The key goal with this technique is to keep well-to-well communication to less than 2% of the injected volume, according to Cindy Taff, the firm’s founder and CEO.

The choice of the geology and fracturing method is critical to ensure that pressuring up the well does not lead to that stored energy flowing sideways to other wells.

It is too soon to say how either version of the subsurface battery concept will be used commercially.

Sage is still conducting demonstration tests and plans to commission its first commercial energy storage facility in December with an electric cooperative in south and central Texas.

When Fervo begins selling power from its Cape Station project, it will be to power suppliers under fixed-price deals for set amounts of power.

However, Fervo has developed a system that can be turned on and off—with a range of settings in between—because its future growth depends on it.

In DOE-funded testing at its Project Red site, Fervo showed it could go through multiple cycles, pumping up the pressure for 12 hours and then producing without pumping for the next 12 hours.

It then pushed the envelope further, far exceeding the few hours of power storage achievable with chemical batteries.

“In one test, we injected for several days while we curtailed production and continued to build up pressure. We then shut down injection and began to discharge the system, which continued to produce power for multiple days,” Norbeck said.

Under normal operating conditions, Norbeck added, Fervo can focus on optimizing input and output based on demand and power prices. “There are a lot of flow profile shapes you can generate by controlling the injection and pumping requirements,” he said.

Engineering Flexible

What these new geothermal tech companies are doing is applying what has been learned about how fractures expand during pressure pumping, and contract when the water flows back.

Norbeck considers this a significant advantage for Fervo, sharing in a press release earlier this year that “the core technology—in terms of the wells and the subsurface engineering—doesn’t change. Once you’ve built the wells, the subsurface system is inherently flexible.”

Another approach to building geothermal systems in hot rock is being championed by Eavor, which is drilling horizontal wells 15,000 ft deep into Germany to supply hot water to heat German homes via extensive district heating systems. This emerging approach uses a closed-loop system with steel-cased vertical injection and production wells, plus an open-hole lateral through the heating zone that is chemically sealed to eliminate permeability.

The system can be turned on and off. But the enclosed heating lines do not offer the expansion potential of fractures.

Unlike Eavor, Fervo and Sage both use hydraulic fracturing, but in significantly different designs.

While Fervo is pumping water from well to well through fractured hot rock, Sage’s system is built around single wells where the water is pumped down to pressure up fractures running down from the lateral.

Sage’s method can be used either to store kinetic energy in pressurized shallower wells, or store kinetic energy and heat injected water for power generation in deeper wells. It plans to commission its first commercial storage facility later this year. In late August it announced a deal with Meta to build a 150-MW commercial facility, but did not offer any details about the timeline or financing for the project.

Those wells are not deep enough to provide the heat needed for generating power as well.

Its next demonstration project will be in Starr County, Texas, for the US Air Force. The well targets a zone down 14,000 ft with rock that is around 400°F.

Sage is drilling its horizontal wells in a type of mudstone that oil and gas companies typically avoid because its properties limit fracture growth. Taff said this largely avoids the leakoff common to naturally fractured bedded shales that are usually targets for hydraulic fracturing.

While Fervo is using the shale industry-standard of plug-and-perf fracturing, Sage is borrowing a method developed by the nuclear power industry called the gravity fracturing method.

As Taff explained, it involves pumping heavy fluid at low rates to create fractures that grow deeper into the subsurface.

“We are allowing the fluid to do the fracturing,” she said. “Because of the weight it fractures downward. You are not pumping at the high pressure or at the rate used for oil and gas fracturing,” Taff said, adding that unlike plug-and-perf, no proppant is required in this process.

After the energy is extracted via the flow of produced water, the Sage system moves the stored fluid through pipelines for reinjection in another well. Taff emphasized there is a notable energy savings earned by pumping the fluid from well to well through pipes rather than through fractured rock.

Sage is also working to enhance the power conversion efficiency of the technology currently at the heart of all geothermal plants, the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC), which must maximize electricity production from temperatures that are at least 200°F lower than those used in fossil‑fueled power generation.

While Sage will rely on the proven technology at its upcoming Starr County project, Taff said Sage is working with the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) to develop on a new “supercritical CO2 turbine,” which is expected to be smaller and cheaper to build than ORC plants with significantly higher heat-to-electricity efficiency.

The energy conversion rate for 400°F water is roughly 10% in an ORC, compared with about 30% for the 600°F water used in conventional power plants.

To lessen that gap, Taff said Sage and SwRI are building the new turbine using a “hybrid Brayton cycle” that will boost conversion efficiency. In addition, Sage is able to capture the energy from water flow resulting in a 25% to 65% higher net power output for its geothermal production.

Taff said the potential energy from flowing water is not as great as its heat content, but “the pressure-to-electricity conversion efficiency is about 90%,” significantly adding to the overall output.

For Further Reading

The Role of Flexible Geothermal Power in Decarbonized Electricity Systems by Wilson Ricks, Princeton University; Katharine Voller, Gerame Galban, and Jack H. Norbeck, Fervo Energy.