Nearly all the shut-in unconventional US wells will be back in production in September, according to a report from Rystad Energy.

Based on early reports the wells are producing at about the level they were before the shut-in, plus a bit extra after operators open them up.

“Nearly all operators said they did not face any issues in bringing volumes back on line as per schedule, as they had already worked on issues such as maintaining reservoir pressure and well integrity even before they began moderating output or shutting in wells,” said Veronika Akulinitseva, vice president, North American Shale and Upstream for Rystad.

While there was talk about shut-ins reducing production, the opposite has often been the case.

“When operators shut in those wells in April–May, the downhole pressure started building, and when the wells are coming back on line now, operators are seeing short periods of increased oil productivity [and] also marginally lower gas/oil ratios in some cases,” Akulinitseva said. Based on the limited data the gains could be 10–15% for a few days up to a couple weeks.

The operator talking about the subject has been EOG, which discussed the added output it calls “flush production” during its second-quarter investor call.

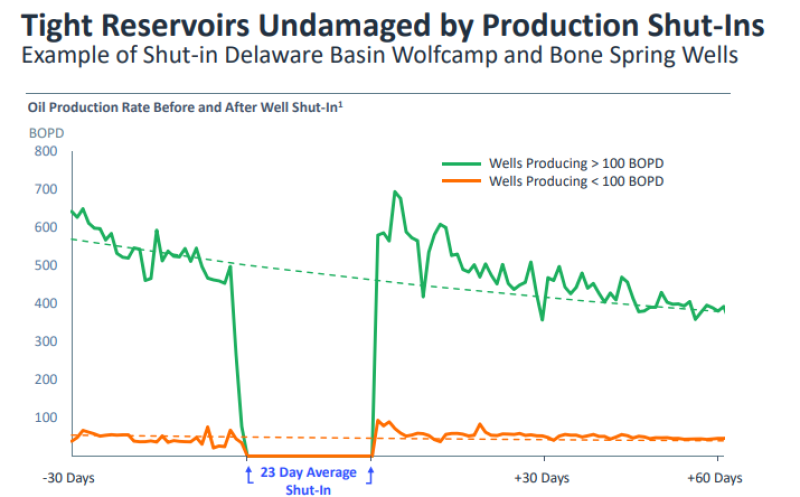

“One observation from our production data revealed that almost every well exhibited some level of flush production before returning to its previous decline profile; further evidence that the well sustained no damage from the shut-in period,” said Billy Helms, chief operating officer for EOG.

The explanation is that when they turn off production on these single-zone horizontal wells, the bottomhole pressure builds up as gas continues to flow in from the formation.

“When we turn them on, those wells will show flush production until that bottom well pressure has gone down to what it was prior to that,” he said.

Helms said it has gone as expected, as shown in a slide from an EOG presentation in May.

A Bit Better

For the year, EOG expects that the flush production plus the post-shut-in oil production that is higher than its “conservative estimates” will be up about 16,000 B/D, or 4% more than predicted.

If this is the case on a large scale, it will answer those who warned that shut-ins could damage wells.

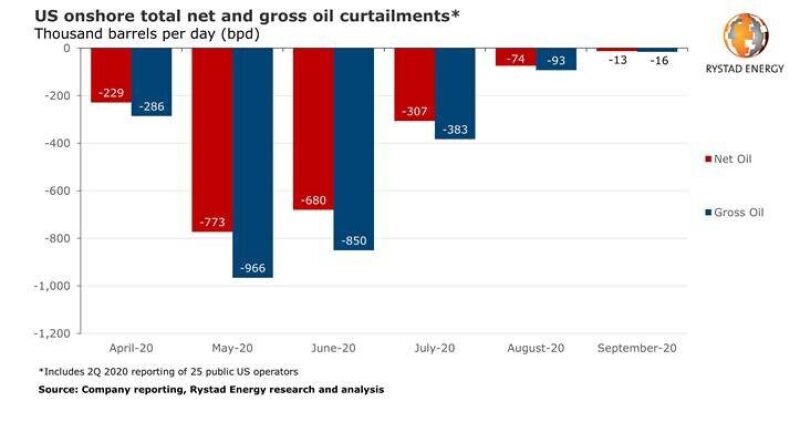

Which is not to say these companies are not losing production as a result of shut-ins, which Rystad said peaked at 772,500 B/D (net) in June and is expected to drop to 74,400 B/D in August.

“They would have done better if they had not shut them in, in terms of cumulative oil production;” said John Thompson, the president of the unconventional reservoir training firm Saga Wisdom.

At the time those decisions were made, maximizing oil production was not the goal. Prices then were flirting with zero and oil demand was so low it was hard to find buyers or storage space. Since then prices recovered surprisingly fast, which has speeded the return of those shut-in wells.

What is not surprising to Thompson are the well results. Based on a petroleum engineering career spent modeling thousands of unconventional wells, many of which had been shut in, these results are in line with what he would have expected.

Despite the “hyperbole” from some financial observers, “what we are seeing here is completely representative of wells in these kinds of plays,” Thompson said.

He said there are some risks. A rapid restart of a young well in an extremely-high-pressure formation, such as the Haynesville, might damage the fracture network, and the hardware in an extremely old well may suffer during a shutdown.

In both cases the risks can be avoided by excluding the young and extremely old wells when planning shut-ins. The restart risk for high-pressure wells can be mitigated by choking production. Maintaining older wells can reduce the risks of their being compromised because their low production limits the potential loss.

Source: EOG Resources

So far, restart data are thin. The latest production data are from June. And other than EOG, companies are saying little about their production restart volumes.

Still, Thompson said, “What EOG is showing is consistent with my observations in 16 years of looking at shale wells.”

When a well is shut in, gas continues to flow into the well, pushing up the bottomhole pressure. When the well is reopening, this reenergizes production.

Also, as the pressure level rises, gas begins going back into solution in the oil. When the well is re-opened, the bottomhole pressure drops and gas coming out of solution helps drive oil out, decreasing the gas/oil ratio for a time.

This year’s mass shut-ins offer researchers a chance to look at how a production break affects a wide range of unconventional wells.

Equipped with data on several wells, Hassan Dehghanpour, a professor at the University of Alberta, said he is working on an SPE paper analyzing what is going on at the reservoir scale which may offer insights on whether low-pressure gas injections could enhance production.

While researchers look for ways to eke out more oil from these fast-declining wells, high-volume drilling is still the only way to sustain production.

Wells that remained in production “are now producing significantly less [depending on their age] than what they produced in March,” Akulinitseva said.

As a result of the drop in drilling, shut-ins, and natural declines, she said US oil production will decline from 12.8 million B/D in the first quarter to 11.2 million B/D in the fourth quarter of 2020.