Editor’s Note: The oil and gas industry is under public scrutiny on a host of health, safety, environmental, and sustainability issues. These concerns affect how companies operate and interact with the public. This series sheds light on how the industry is actively addressing these challenges now and in its goals for the future.

As has been pointed out before in JPT and elsewhere, “sustainability” is a multifaceted word. The industry has seen the risks inherent in each upstream sector defining the word in narrow ways. These multiple perspectives are a natural result of a global scope, despite a growing ability of the parts to work in harmony, especially during a time when unity in the face of the challenge posed by the COVID‑19 pandemic is a necessity. Nevertheless, social responsibility remains a critical component of any drive to achieve sustainability. Central to social responsibility is the notion of safeguarding human rights, an idea seldom mentioned specifically in the literature.

Three recent SPE conference papers, however, prove that this concept remains prominent in the minds of industry professionals. Two papers discuss the importance of guaranteeing the respect of human rights along the supply chain, where developing-world labor is at particular risk of being preyed upon without recourse to justice. A third paper links the human rights aspects of corporate social responsibility (CSR) to the broader idea of sustainability by explaining the benefits of institutionalized transparency in reporting the social impact of oil and gas operations. All authors argue that from both ethical and economic perspectives, human rights are a key component of sustainability.

Petronas authors provide an overview of the implementation of human rights measures in the operator’s supply chain since the establishment of the company’s Human Rights Commitment in 2015 (SPE 195408). It involved embedding relevant human rights elements throughout the entire supply chain management process, starting from contractor licensing and registration to the performance evaluation of contractors at the end of the contract life cycle. The four human rights elements comprise fair and humane labor practices, security training that emphasizes avoiding the use of excessive force, the review of supply chain contractor adherence to humane practices, and the promotion of health and safety in communities involved in the supply chain. Furthermore, the operator adopted a covenant the authors refer to as the Contractors’ Code of Conduct on Human Rights that is mentioned explicitly in general terms and conditions of all contracts.

The authors demonstrate that a proactive approach in managing human rights is crucial to sustaining the company’s long-term growth. The implementation of human rights in the supply chain is a continuous journey as the company develops partnerships with contractors in the future; thus, continuous collaboration between both company and contractors is key to the success of this shared commitment. This collaboration will also meet growing stakeholder expectations for the operator to safeguard human rights. The operator has emphasized the positive effects of these measures on contractors, who are empowered to understand how operationalizing human rights can benefit the industry in the long term.

Another paper explores the crucial junction of human rights and the supply chain (SPE 197835). The paper opens with a statistic from the International Labour Organization that 25 million people around the world survive in conditions of forced labor, most of these working in the supply chains of global business. If the UN Sustainable Development Goal 8—sustained, inclusive work and economic growth—is to be realized by 2030, businesses and governments must do more to address these issues. In 2018, for instance, only 36 countries were taking steps to develop legislation and investigate forced labor in business and government supply chains. The Petrofac author wrote that ethical requirements can work in concert with a strong business case to improve supply chain labor rights worldwide.

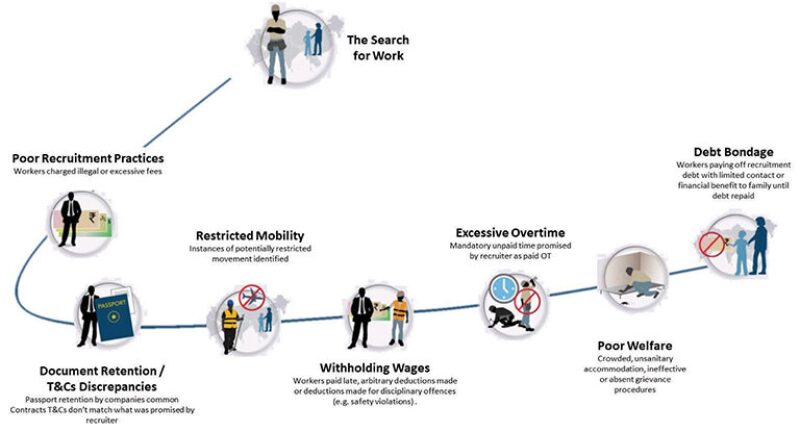

He added that Petrofac recognizes that major human rights vulnerabilities exist in the supply chain and, more specifically, in the employment of migrant workers from countries in which un-ethical labor practices are prevalent. Such practices include the charging of excessive recruitment fees, unconsented retention of passports, and the risk of contract discrepancies during recruitment (Fig. 1). The paper describes the implementation of a rights and worker welfare program to address these risks, including adoption of a new labor-rights standard, and diligence and governance structures designed to ensure that contractors adhere to humane policies. These steps ensure sustainability in two contexts: The public perception of ethical business behavior—of increasing importance to the industry—and that of the business case, which benefits from increased efficiency and employee engagement.

The third paper discusses the adoption of CSR in Nigeria (SPE 198776). While many companies have used philanthropy and the foundation of strategic partnerships to enhance CSR, others have increased their dedicated expenditure on CSR. To derive maximum value, companies need to report with certainty the direct and indirect impact of their contributions to sustainable development; still, challenges exist in guaranteeing the transparency and accuracy of such measures. Many CSR projects have failed shortly after completion and transfer to beneficiaries, partly because of an initial failure to incorporate a robust set of sustainability criteria into the design and implementation process. On the other hand, attempts to measure project impact after completion sometimes do not yield desired results because of deployment of poorly designed methodology for data collection and analysis.

The paper provides guidance on sustainability assurance and evaluation criteria that can assist companies in moving beyond annual reporting on the number of completed projects and the amount of money spent, to more accurately describing the impact of projects on beneficiaries, as well as macroeconomic, social, and environmental effects. The author concluded that knowledge and full understanding of the effects of completed community development projects are crucial for effective CSR communication as well as lessons for the planning and delivery of subsequent projects. A CSR strategy with appropriate key performance indicators, realistic targets, and established processes to measure social outcomes is crucial to ensuring that companies achieve the greatest benefits for society from their CSR budgets and sustainability in their regional operations.

In the face of the struggle being waged worldwide against COVID-19, set against a calamitous plunge in the price of oil, the idea of “sustainability” has recently achieved an uncomfortable new dimension for many SPE members. The industry must do its part in that struggle as it undergoes its own transformation. However, it must also not lose sight of the fact that central to any societal improvement is the idea that dignity must be protected, and that comfort for some cannot justify injustice for many. The central theme of the described papers—that the world’s labor force, despite well-meaning efforts by many actors, remains vulnerable to exploitation—proves that many professionals are dedicated to the same notion that propelled oil and gas to its central role in modern society and economics: An improvement in quality of life is desirable and achievable and can be sustained.

References

SPE 195408 Advocating Human Rights in the Supply Chain by Raja Tatina Raja Musa and Jing Yi Heng, Petronas.

SPE 197835 Turning Challenge Into Opportunity: Enhancing Worker Labor Rights Through Supply-Chain Collaboration by Gregory Ross, Petrofac.

SPE 198776 Sustainability Assurance and Evaluation for Effective Corporate Social Responsibility Communication by E. Ite Uwem, Oriental Energy Resources.