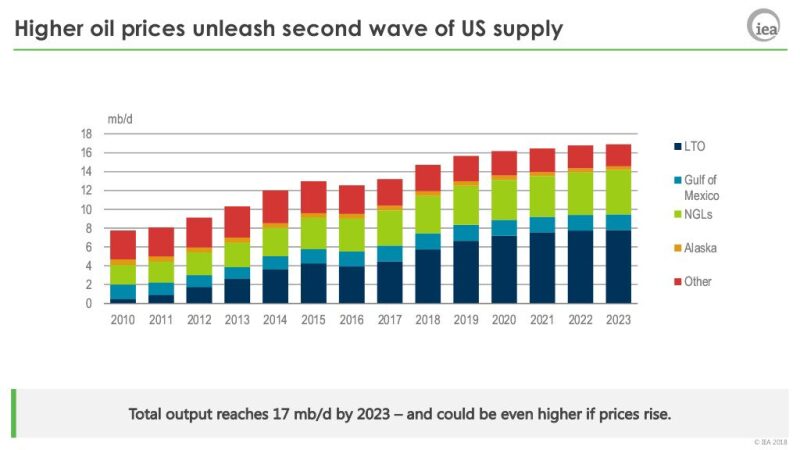

US crude production is projected to surge to 12.1 million B/D by 2023 amid "a second wave” of shale output increases, making the country the world’s largest oil producer, according to the International Energy Agency’s latest 5-year market forecast.

The new wave is underpinned by higher oil prices following the pact between OPEC producers and a group of non-OPEC countries to collectively curb output through this year. “Everyone has benefited” from the deal, and newfound optimism has spread through the industry, said OPEC Secretary General Mohammed Barkindo during the CERAWeek conference by IHS Markit in Houston.

While OPEC may be sacrificing market share for market stability, Barkindo nonetheless said the collaboration “is as solid as the rock of Gibraltar” and could be institutionalized going forward. He believes the consensus is that an ongoing pact is necessary to serve as an insurance policy against price shocks like the one that occurred during 2014–16.

Barkindo, who in the past lamented the unrestrained nature of US shale output spikes, was set to have a “dialogue” with executives from shale operators on the evening of 5 March. US crude production hit an all-time monthly high in November and is expected to post a yearly record in 2018, the US Energy Information Administration reported last month.

The US “is set to put its stamp on global oil markets for the next 5 years,” said IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol, who added that rising shale production should be a factor taken into consideration by OPEC and non-OPEC partners when discussing further possible output restraints.

The IEA forecasts that overall US production gains will represent 60% of new global output to 2023. Over the next 3 years, it will cover 80% of the world’s demand growth, with fellow non-OPEC countries Brazil, Canada, and Norway providing the rest, growing 1 million B/D, 790,000 B/D, and 450,000 B/D, respectively.

Birol sees “no peak oil demand in sight” as the IEA forecasts yearly demand growth of 1.2 million B/D, about half of which will come from China and India. While growth in India will rise slightly, China’s growth rate could slow due to the country’s new industry policies designed to reduce pollution. He noted the global petrochemical sector is “one of the blind spots of the oil market debate.” The IEA projects new petrochemical capacity to represent 25% of oil-demand gains by 2023, driven by projects in the US and China.

As an exporter, the US will continue to lift its profile in world markets, the IEA forecasts. Following relief of some transportation bottlenecks associated with crude movements from Canada and within Texas, US capacity is expected to approach 5 million B/D by 2020 as Corpus Christi becomes the primary North American crude outlet. While the first wave of increased US oil production was largely absorbed by domestic markets, much of the second wave will provide feedstock for European and Asian refiners.

Due to sheer volume and geography, however, the Middle East will remain the most critical region in the world for oil resources, and Saudi Arabia will remain the biggest and most important exporter “for many years to come,” Birol said.

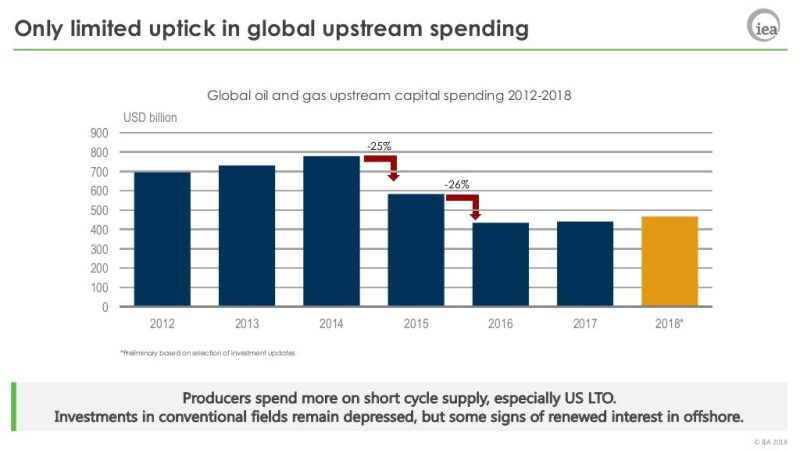

Given their shared expectations of rising global demand and continued production declines from aging fields, Barkindo and Birol both emphasized the need for more upstream investment from regions outside the US to maintain market stability in the 2020s. Global spending dived 25% in 2015–16 before staying flat in 2017, and early data suggests only a modest rise in 2018.

Meanwhile, there has been an increasing focus on short-cycle projects at the expense of more expensive, often more rewarding long-cycle projects. Birol noted “the world needs to replace 3 million B/D of declines each year—the equivalent of the North Sea.” Those potential shortfalls could result in market volatility that is quite different from what OPEC and non-OPEC collaborators have recently sought to remedy, he said.