Mike Watts is the cofounder of Magna Energy, an exploration and production (E&P) startup with no operations and a contrarian business strategy targeting Indian oil and gas.At a recent presentation in Houston promoting India’s upcoming bid round of small field discoveries, Watts, who led Cairn Energy’s exploration program when it made big deals and discoveries in India, played up the country’s unrealized oil and gas potential.

“You need to be passionate and believe in the geology of India,” Watts told the 150 people who attended the road show publicizing the bid round. Based on his experience dating back to the 1980s, he believes India “is vastly unexplored compared to the potential.”

His vision has the backing of Carlyle Group, a private investment bank, which committed up to USD 500 million to support Magna’s program to build production and reserves in India.

The upbeat mood of the road show contrasted with the dark mood of the current global oil business. India is “a big growing market which is a bright spot in an unsettled world economy,” said Dharmendra Pradhan, India’s minister of Petroleum and Natural Gas.

The sale is an early test of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s program to expand domestic oil and gas production, which has included sweeping regulatory changes in the world’s third-largest energy-consuming country.

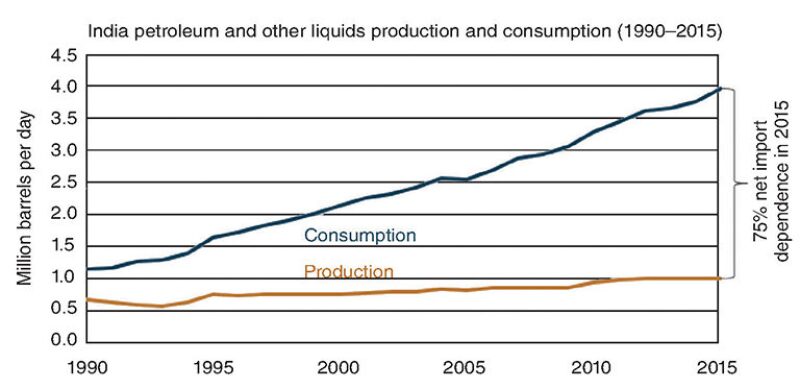

If the country is unable to increase its flat oil production trend line, the International Energy Agency predicts that India will be importing 90% of its oil by 2040 to meet its needs.

“India has a dependence on imported oil and gas, and a clear policy has been set in place to relieve this dependency and that presents tremendous opportunities in the E&P sector,” said Atanu Chakraborty, director general of the Directorate General of Hydrocarbons, which is running the auction of properties relinquished by the state-owned Oil and National Gas Corp. (ONGC).

Mixed Emotions

Consultants in India agree there is reason to be upbeat about India’s future, but they are feeling the global oil slump.

“The last 18 months have been very hard,” said Ashish Chitale, who runs Praesagus RTPO, the Indian partner for the consulting firm Sierra-Hamilton. “All the excitement is potential excitement.”

The buzz is over changes in policies that long stifled exploration in a country where about 60% of the sedimentary basins onshore and offshore have seen little exploration, according to the IEA India Energy Outlook. The new rules are designed to ensure market prices for gas, reduce legal and regulatory battles over contracts, bring new companies into the business, and eliminate custom duties on imported oilfield equipment.

The bidding round, which is under way and concludes 31 October, is a test of the government’s ability to smoothly auction exploration prospects before a much larger sale that it is planning for the near future.

“The big companies are not interested in [bidding in] this round, but they are watching closely now for signs how the next round will go,” said Rachel Calvert, manager for Asia Pacific Petroleum Sector Risk at consultancy IHS. She added that, “The regulatory system is backing up what they are trying to do, interest is up, but it is a difficult oil market out there now.”

The current offerings are discoveries relinquished by state oil companies, some of which were drilled as far back as the 1970s. Most were dropped for good reasons, such as being small or complex, but Watts said he is interested because “there may be some hidden gems.”

With so many producing properties for sale around the world at attractive prices, the likely bidders will be operators focused on the Indian market and who are looking to make connections with government officials that might benefit them in future sales.

“From an Indian perspective, it is really good. From an outsider perspective, seeing what is available elsewhere, this is not up to that league. It is a different perspective,” said Balaji Chennakrishnan, founder and chief executive officer of Telesto Energy, an energy consultancy.

De-Risking Regulation

For Chennakrishnan, who started his career 23 years ago in India, the government’s changes are striking. The effort has changed the business climate that has limited past exploration and soured relations with some large international oil companies. “I have never seen a proactive government like this before,” he said.

A big question facing bidders on properties that demand a long-term commitment: How long will these reforms last? Prime ministers and ruling parties come and go. But the 2-year effort is having a positive impact. One sign is the country’s improved grade in IHS’ evaluation of the risk of doing business there.

The long list of positives include new licensing terms based on revenue sharing rather than profit sharing, which has been a source of audits and litigation; new pricing rules; leases with no time limit on exploration; and a new dispute resolution procedure. That last item, called the “empowered committee of secretaries” was created to encourage various government agencies to cooperate to streamline rules and resolve contract disputes outside the legal system.

Changing in pricing rules will offer more attractive gas prices for some fields, but not others. Gas from deepwater offshore, or from high-pressure/high-temperature fields onshore are offered at a higher rate, which Calvert said is now about USD 7/Mcf.

Other fields will command a price based on what is considered an “arms-length deal.” The goal is prices reflecting global markets, but there are no pricing benchmarks, such as a futures market contract tracking the South Asian gas market. The price of imported liquefied natural gas has been used for price setting, but the global gas glut has led to a range of negotiated prices rather than a price pegged to the price of oil.

New rules also eliminate limits on drilling in producing fields that were no longer in the “exploration phase.” The notion that exploration and production are clearly defined phases does not reflect real-world operations where “production always finds more production,” Chitale said.

The rules have also been changed to encourage startups of local independent exploration firms by successful entrepreneurs from outside the business. Bidders no longer have to demonstrate they are experienced in the oil and gas business.

“Over the past 2 years, the new government and new ministers have taken a look at what works around the world and what is different. One thing they have been struck by is how much of a difference the independent-driven oil and gas companies make in the US,” said Chitale.

“For small entrepreneurs entering into oil and gas it is a good time,” Chennakrishnan said. Independents can make money where ONGC did not because they have “a totally different way of working and totally different economics.”

A telling detail in the tax rules is an exemption of custom duties on the many types of equipment and services that must be imported in a country lacking oil technology suppliers.

India’s energy regulators want to take advantage of the country’s vibrant digital technology sector. Singapore-based Telesto has partnered with Next Technologies to create an information technology center in India providing advanced analysis to its clients in the oil and services sectors. While the main goal is increasing its domestic oil supplies, the oil-technology-short country is also hoping to build a domestic service and supply sector.

Seeking Potential From Disappointing Discoveries

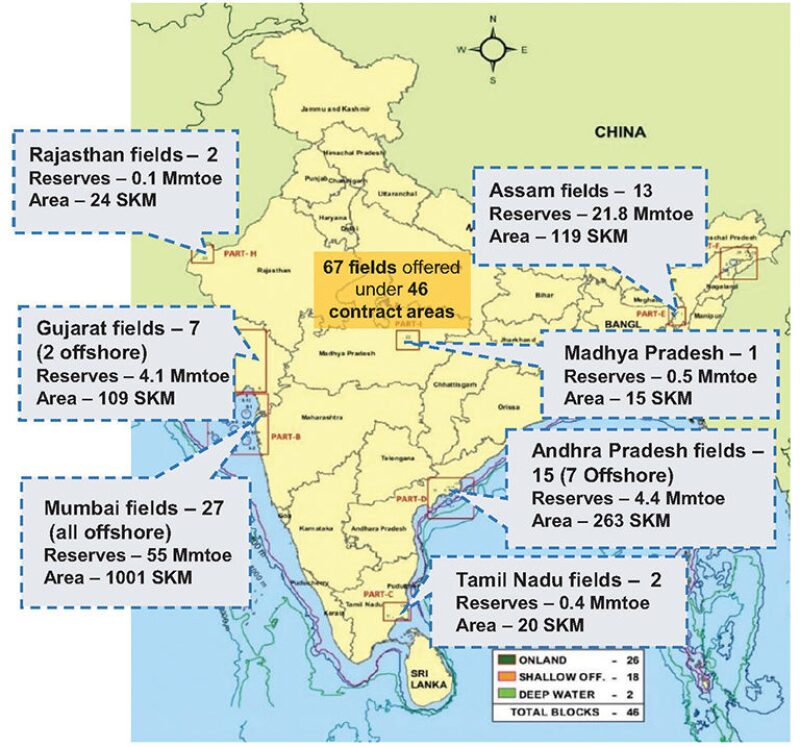

Those who have looked closer at the 67 small fields offered in India’s current bid round see some potential pitfalls.

“There are opportunities for small investors and some hidden opportunities that have not been exploited, and some areas to be careful about,” said Balaji Chennakrishnan, founder and chief executive officer (CEO) of Telesto Energy, an analytics-driven energy consultant.

In the majority of the fields, a single well was tested before the project was dropped by the state-owned oil company. The discovery dates range from 1970 to 2012, with the largest number in the 1980s and 1990s.

“There are 46 blocks on offer including clusters. There are six or seven that are really good, and another 12 to 13 are worth a deeper look. The rest are a no go,” said Chennakrishnan.

On the plus side, some reservoirs offer multiple zones with production potential where only one was tested. There are also fields abandoned because production from a well was limited due to a poor completion or wellbore damage caused during drilling, he said.

There are opportunities for those who can manage deep, high-pressure/high-temperature fields or apply new concepts and technology to deepwater plays, said Mike Watts, cofounder and co-CEO of Magna Energy.

When a similar auction for small and medium-sized fields was held in the early 1990s, there were a lot of productive properties in the mix. Back then “28 fields were auctioned and 25 are operational now,” said Amar Nath, joint secretary of the ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas.

At the top of the list of success stories from that round was the Ravva field located off the eastern coast of India, which is still producing 16,000 BOE/D more than 20 years after it was awarded to a joint venture operated by Cairn, which has continued to incrementally add production.

In the current bid round, the limited time between when the data rooms were opened in July and the sale’s conclusion in October puts a premium on making the most of the available data, which generally include seismic data and well logs. Also, knowledge of nearby production and similar fields, as well as local conditions, are critical when evaluating the prospects.

“When it comes to field evaluation, there are still some challenges. The data is often scarce and old. If I am going to make a business case to management I have my work cut out for me,” said Ashish Chitale, who runs Praesagus RTPO, the Indian partner for the consulting firm Sierra-Hamilton, adding, “If you have access to good seismic reprocessing, you might want to get it done. It will offer a starting point for evaluating the upside.”

The above-ground costs are just as variable and critical for evaluation. Bidders need to research what is available upfront and negotiate prices for services beforehand, he said. Bidders must weigh the price of natural gas and the cost of local exploration and production services. The cost and quality of data and infrastructure will depend on state-owned oil companies.

At a recent presentation in Houston, the head of Oil and Natural Gas Corp. (ONGC) promised to offer access to data on nearby fields as well as to pipelines and processing.

“ONGC and Oil India will fully support the use of these areas by making facilities available to them,” said Dinesh K. Sarraf, chairman and managing director of ONGC.

Some of those facilities are going to be hard to reach. For example, in the state of Gujarat, a slide presentation showed that ONGC processing facilities were from 10 km to as much as 70 km away from fields. As for the price, Sarraf said the company “will share facilities for a reasonable consideration.”