Years in the making, the recent steady rise in drilling in the Powder River Basin of northeast Wyoming is generating excitement reminiscent of the early days of currently more-established US onshore oil plays.

The upturn in activity is resulting in double-digit production growth. Wells are bubbling over with oil, and operators are bubbling over with enthusiasm. This has been most evident in recent industry presentations, where decision makers from the basin’s exclusive club of operators have gushed over what is becoming a core asset in their portfolios.

Given the basin’s oil richness, multiple stacked horizons, and well performance and economics, “we think it’s comparable and competitive with the big-name basins—whether it’s the Permian, SCOOP, or STACK,” Joseph DeDominic, president and chief operating officer of Anschutz Exploration, said at a recent SPE Gulf Coast Section meeting on the basin.

“This is what really gets us excited—the fact that you have 5,000 ft of stacked pay which is very similar to what you see in the other basins,” generating a high-dollar amount per acre, said Aaron Ketter, vice president of Devon’s Rockies business unit, during the same event. Formations are “highly economical” at $50/bbl and under, he said, with the heart of the Turner zone sometimes breaking even in the high $30s/bbl.

Traditionally known for its prolific coal production, the Powder River Basin’s potential for oil became a stronger point of focus in the industry about a decade ago. Operators began moving in on the region, rigs in tow, collecting limited but valuable data on its formations. When the commodity price downturn struck the industry during 2014–2016, operators pulled back investment, resulting in the basin’s failure to launch.

In its current state as an oil play, the basin is still underdeveloped. While lots of vertical wells have been drilled there in the past, “the truth is, when you look at horizontal development, and even using modern completions, it’s really brand new. We’re just getting started,” said Joseph A. Mills, Samson Resources II president and chief executive officer. “Delineation is what’s happening today and that’s probably what’s going to go on for another couple of years.”

Companies that are now ahead of the curve arrived early in the basin, secured operatorships, began drilling years ago, held onto their acreage—and its accompanying data—through the downturn, and patiently waited for oil prices to rise and costs to fall.

“What’s unique about the Powder is just the areal extent of some of these zones aren’t the same magnitude as you see in the Permian or the Midcontinent. So zip code really matters,” said Ketter.

Current Lay of the Land

Devon, Anschutz, and EOG Resources have the largest positions in the Powder River at around 400,000 net acres each. Chesapeake Energy and Anadarko Petroleum each has around 300,000 net acres, with the latter firm having just spent some $100 million to expand its position.

Oil and condensate production from the basin is forecast to jump 25,000 B/D this year to 136,000 B/D and continue rising next year above its 2015 high of 144,000 B/D, according to data provided by research consultancy Wood Mackenzie. The rig count this year is seen alternating between 13–16. EOG, Devon, and Chesapeake have been the leading producers over the last several years.

“The Powder River Basin is one of the more oil-prone basins in the Rockies with stacked pays throughout,” said Stephen Sonnenberg, professor, geology and geological engineering, at Colorado School of Mines. He sees “enormous resource potential yet to be had” there.

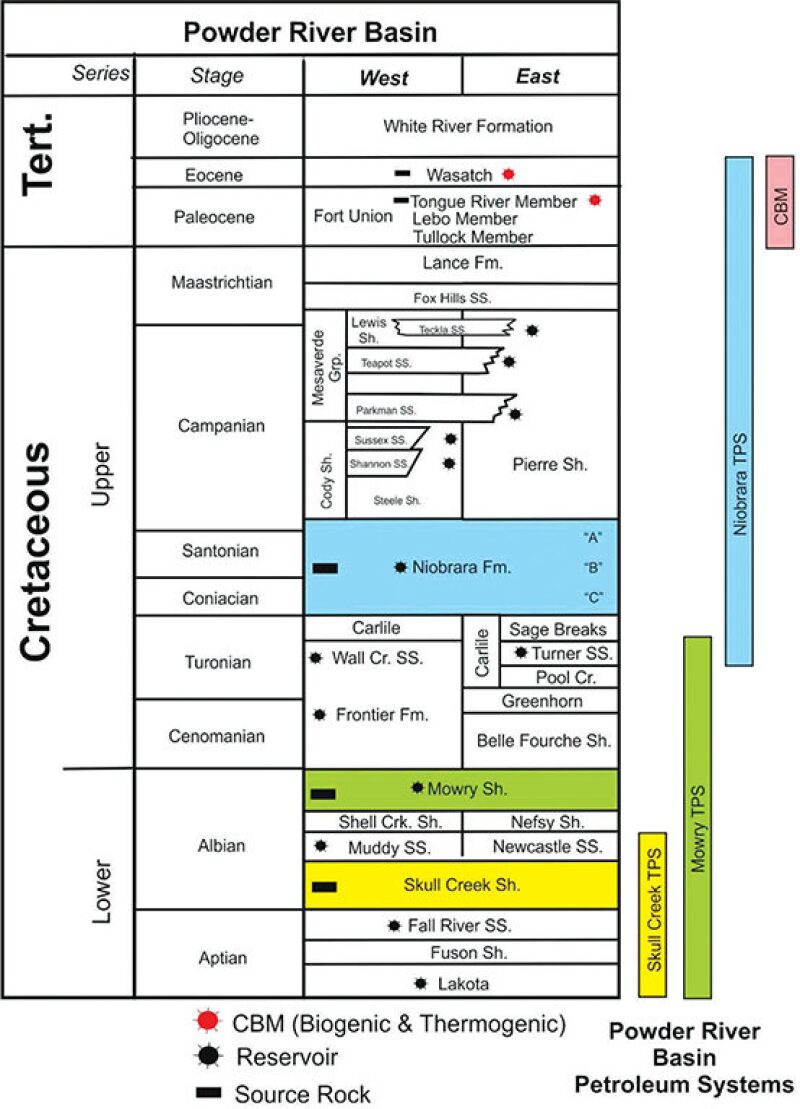

The Powder River is known for Paleozoic oil production via the Minnelusa and Leo formations as well as several zones in the Cretaceous that contain oil, including the Fall River, Muddy, Mowry, Frontier, Turner, Niobrara, Sussex, Shannon, Parkman, Teapot, and Teckla.

The upper targets are tight sands with higher permeability than shale plays. “The Parkman, Sussex, Shannon, Teapot, and Teckla are more conventional in their trapping style,” said Sonnenberg. “The updip parts of these reservoirs—thinly bedded zones or bioturbated facies—are now the target for horizontal drilling with great success.”

Deeper reservoirs are found via the Turner, Frontier, Niobrara, and Mowry, which have especially drawn interest from operators as higher commodity prices and technological advancements have made development of those zones less cost-prohibitive.

Though often informally referred to by the industry as a formation, the Turner actually is a member inside the Carlile formation, which is “kind of what makes it so good,” noted Brandon Myers, Wood Mackenzie upstream research analyst. “It’s this decently porous, permeable sandstone wedged between two tighter shaley sandstones,” which seal in the pressure and hydrocarbons, making the reservoir “quite charged,” he said.

Still in the testing phase as horizontal developments, the Niobrara and Mowry are widely regarded as highly prospective unconventional formations. The very southern portion of the Niobrara in the Powder River, where many wells are clustered, “looks somewhat like the Niobrara in the DJ Basin,” Myers said. The historic Salt Creek and Teapot Dome fields in the Powder River produced in part from the Niobrara but in the shallower, flanking structure of the basin.

“The Niobrara is turning out to be a major play in the Rockies, and the Powder River Basin may be one of the largest accumulations in the Niobrara,” Sonnenberg said.

Finding New Life in the Powder

The fortunes of the recently reborn Samson Resources will largely hinge on the Powder River, including the Niobrara, after its transformation into a pure-play Wyoming operator from a gas-focused company spread across several basins. The company entered the basin about a decade ago and focused on the Sussex formation. Leading up to 2014, the company also drilled deep into the Mowry with an eye toward the future.

“We drilled several pilot wells, took a number of cores in both the Niobrara and the Mowry, built a lot of analytical work around them since 2014, and became more and more convinced that the real upside potential was in the Niobrara and the Mowry,” said Mills. “If we can unlock the secret to both the Niobrara and the Mowry, then the growth potential will be large.”

The company’s position consists of 152,000 acres that “basically sit on the geological axis of the basin,” Mills explained. “So we’re in the deepest portion of the basin, which means it has the thickest section and it’s the most overpressured.”

After emerging from bankruptcy last year, Samson participated in the drilling of multiple conventional zones, including several big Turner wells operated by Anschutz or Chesapeake. “We learned a lot from their drilling practices as well as their completions activity, so we’re taking that into account in our upcoming drilling program,” he said.

Mills observed that days to total depth “have come down pretty dramatically,” with some Turner wells being drilled in 20–25 days, down from 30–35 days a year ago. Operators have become better at hitting their landing zones, which is critical in the Turner, where the sweet spot can be 40–50 ft in a 250-ft gross interval.

“On the completions side, bigger is not always better,” he noted. “And we’ve seen how choke management can make a difference in terms of how you pull these wells. It’s always great to have that IP 24, IP 30 [24-hr, 30-day initial production rates] where you can make a splash, but it’s really how you manage the flowback rates. A lot of our competitors have been producing up the casing for a period of time; some go right to tubing and really manage the chokes. We’ve seen it has an impact on the estimated initial recoveries 90 days, 180 days, 360 days out.”

He noted, however, that those learnings do not necessarily apply to tighter unconventional formations, where much more proppant is needed.

Samson recently spudded its first well, the Spearhead Federal, with its first operated rig in the basin since 2014. It will test the conventional Shannon formation in the northwest corner of Converse County. A second rig is expected to be added by the end of October, and eight wells total will be drilled, consisting of two tests each for the Shannon, Frontier, Mowry, and Niobrara. The first rig will focus on delineation, while the second rig will focus on development.

The goal is to add the second rig before federal stipulations take effect. “Stips,” as they are informally called, limit drilling and fracturing activity during certain times of year to protect native wildlife. “It’s a constant logistics game to keep up with the stip windows and make sure that you’re staying ahead,” Mills said. Powder River operations in particular are affected by the breeding of sage grouse and nesting of raptors, both of which occur around springtime.

“Next year, for sure, we’ll keep two rigs running, and with some success, we hope to go to three,” he said. “We will then go to pad drilling as we start to really test the spacing concepts. That is a big question mark today.”

Operators in the basin tend to have different views as to the best spacing patterns. For its conventional formations, Samson believes 2–3 wells/drilling and spacing unit (DSU) are required to effectively drain a conventional reservoir. However, most companies are permitting 4 wells/DSU. “Chesapeake is leading the charge on some of their spacing, and we’re all watching with great interest,” he said. Samson is not involved in Chesapeake’s current wells.

With the unconventionals, most companies are permitting for 8 wells/DSU, though nobody’s drilled eight wells in a DSU yet, Mills said. “Quite frankly, there’s probably only been a handful where two or four wells have been drilled. EOG in particular has done some pilots.”

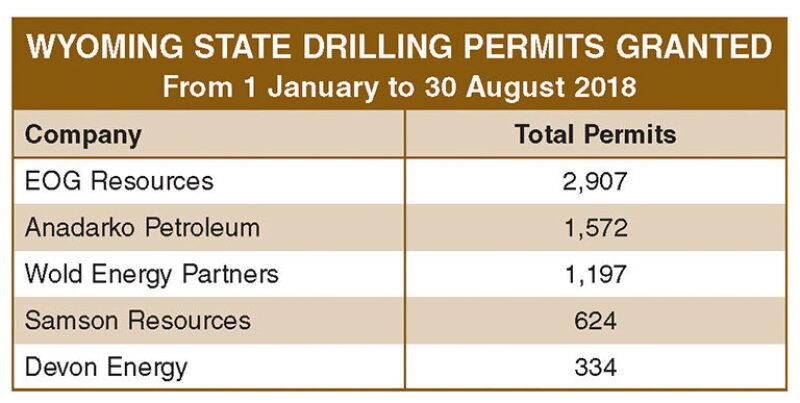

Race for OperatorshipDesire by exploration and production companies to stake their claims to the Powder River Basin has created an unprecedented volume of drilling permit filings and hearing activity for the Wyoming Oil and Gas Conservation Commission. “Lately we’ve been having 400–500 hearings a month, and then we’ve got 10,000–12,000 drilling permits in the queue,” said Mark Watson, the commission’s agency director. All the while, the commission has been trying to keep up “with the same staff we’ve had for the past 20 years.” Most of the hearings are held to determine drilling and spacing units, after which the commission proceeds to reviewing permits.

The influx of permits has been part of “a race for operatorship,” Watson said. In Wyoming, multiple companies that intend to participate in a well can file a permit to drill, but the one that is granted the permit becomes the well’s operator, even if it holds only a tiny stake in the acreage. As a result, the biggest independents in the basin have reacted by submitting a barrage of applications (Table 1). “I think EOG came in with in excess of 5,000 drilling permits,” he said. Other companies outpacing their peers in submissions have been Anadarko Petroleum, Wold Energy Partners, Anschutz Exploration, and Samson Resources II. While Devon Energy has also been an active filer, it has submitted significantly fewer applications compared with those companies. Notably missing from the list is Chesapeake Energy. For the bulk of their acreage, Chesapeake and Devon opted to form federal exploratory units through the US Bureau of Land Management. Chesapeake was the first to take this approach as it prepared for horizontal drilling in the Niobrara. “A lot of federal units are trying to be formed right now,” said Joseph A. Mills, Samson president and chief executive officer. Federal units allow for the permitting of up to 25,000 acres where little-to-no exploration activity has occurred. It designates a single operator among, in some cases, dozens of partners, removing the need to file permits early and often to secure control of drilling and production work. A unit is challenging to form, mainly because there are often differences of opinion between the partners as to who should operate it. To ensure the commission first approves permits for companies that actually drill, Watson revised its policy earlier this year to require applicants to submit a spreadsheet with their rig schedule for the following 6 months. Applications that have a solid drilling plan with near-term commencement are given priority for review. This promises to weed out companies that receive permits and then just sit on them—whether it is because they really are not ready to drill or for other reasons: In some cases, permits holders, instead of drilling, will sell them to other companies that are looking to increase the value of their property. “There’s been a lot of the horse trading going on,” Watson said. He is also hopeful the permitting process will speed up now that the commission has moved to an electronic-based system. Companies can file their permits online, relieving the commission from manually gathering and inputting that information. It especially helps given the limited resources and personnel working at the commission. While both have been adequate thus far, Watson said the commission could always use a few more engineers and field techs. “Unfortunately, the last couple years in Wyoming, with our revenue decrease, we’ve had a hiring freeze, so it’s been hard to actually hire people. But I think if it gets too busy the government can get a few more people.” |

Big Operators See Big Results

Chesapeake and EOG, the two more-established players of the Powder River, made waves during second-quarter earnings season as the basin was their primary topic of discussion. The main takeaway: They are seeing results, they are liking them, and they are committed to investing in the Powder River. In the case of Chesapeake, so much so that it characterized the basin as developing into “the oil growth engine of the company” as it simultaneously announced the divestment of its Utica Shale assets.

The Oklahoma City independent provided strong numbers to showcase its progress in the basin, saying it expects its net production there to reach 38,000 BOE/D by year end after averaging 18,000 BOE/D in fourth-quarter 2017.

Bolstering the output surge, five Turner wells were brought online in late June and early July with IP rates ranging 1,500–3,200 BOE/D, of which 65% was oil. The company in July added a fifth rig—all five are focused on the Turner—and said it’s exploring adding a sixth rig in 2019. Chesapeake originally planned a three-rig program when it put together its 2018 budget, meaning the company has shifted capital into the basin.

Doug Lawler, Chesapeake president and chief executive officer, noted that drilling times on three recent Turner wells were “less than 20 days from spud to rig release and total cycle times are now in the 90-day range.”

As it ramps up activity, Chesapeake is getting a better idea of what works. The company in April tested reduced spacing by bringing six Turner wells, spaced 1,980–2,300 ft apart, on production. On 1 August, it said all six wells were performing on par or better than previous wells spaced 2,640 ft apart.

Meanwhile, it has determined that its “historical Niobrara wells were severely understimulated and, quite frankly, drilled probably too tight a spacing,” said Frank J. Patterson, Chesapeake executive vice president of exploration and production. “So, we’re going to up-space, put longer wells in the ground, and put bigger fracs on the wells.” He mentioned that among three wells for which Chesapeake used larger fracs was the Barton well, a 10,000-ft lateral drilled in 2015 that’s “the best [Niobrara] well in the country.”

For EOG, the Powder River is now its third-largest asset. The Houston independent reported a combined estimated net resource potential of 2.1 billion BOE from the Mowry, Niobrara, and Turner. Operating a two-rig program this year, EOG plans to increase its drilling activity during 2019 and install additional infrastructure before initiating a long-term development program. The company notes that well costs are “down significantly.”

Most promising for EOG is the Mowry, where its estimated net resource potential totals 1.2 billion BOE from 875 net premium locations using 660-ft spacing. During the second quarter, the Ballista 204-1102H and Flatbow 423-1720H wells were completed with an average treated lateral length of 9,100 ft/well and average 30-day IP rate of 2,190 BOE/D per well, of which 760 B/D per well was oil. Well costs are targeted at $6.1 million for a 9,500‑ft lateral.

In the Niobrara, EOG has estimated net resource potential of 640 million BOE from 555 net premium locations also on 660-ft spacing. The Ballista 213-1301H well was brought to sales in June 2016 with a treated lateral length of 9,500 ft and 30-day IP rate of 2,090 BOE/D, of which 1,180 B/D was oil. Targeted well costs are $5.9 million for a 9,500-ft lateral.

The Mowry and Niobrara overlap on much of EOG’s acreage, “allowing development of both concurrently,” said David W. Trice, EOG executive vice president, exploration and production, during his firm’s earnings call. “Tightly spaced wells and codevelopment also translates to less surface disturbance per well, which reduces our environmental footprint and is particularly important for permitting in Wyoming.”

In the second quarter, EOG completed seven Turner wells with an average cost of $4.1 million/well. They were completed with an average treated lateral length of 6,200 ft/well and average 30-day IP rates of 915 BOE/D per well, of which 760 B/D per well was oil. Trice said the company has been able to drill 2-mile Turner wells in 6–7 days, with zipper frac operations allowing for up to 10 stages/day.

Figuring It All Out

Devon, the other top producer in the Powder River, has also spoken highly of its Turner wells but has stopped short of disclosing well results. The company has conducted spacing tests, and now is “starting to define what the development plan will look like,” said Tony Vaughn, Devon chief operating officer, during his firm’s second-quarter call.

Vaughn said the company plans to add a second and third rig to the basin this year and in 2019 expects “to be in full development mode there with increased activity beyond that.”

In addition to the Turner, Devon’s current top targets are the Parkman and Teapot. Parkman and Teapot wells have “sizeable 30-day IPs” with drilling and completion costs of $4–5 million/well, making them competitive with the company’s wells in the STACK and Delaware, said Ketter, during the recent Gulf Coast Section event.

The company is currently trekking deeper into the Niobrara and could possibly do the same into the Mowry this year or next. Ketter said the Parkman, Teapot, and Turner currently have “better deliverability and well economics in their relatively smaller sweet spots” and “provide enough quality locations to be valuable targets in the near to medium term.” But, compared with the Niobrara and Mowry, Devon believes “they are less material in terms of total available resource,” he added.

Gaining a better understanding of those unconventional formations will be essential to the company’s Powder River evolution. Ketter told JPT that Devon has been sharing some production and subsurface data with other operators “on a targeted basis” in an effort to expand its data set. The company is also drawing insights from its other core assets. “Every day, engineers and geoscientists from the other basins are sharing successes and failures with the Powder River team,” he said.

“Devon has acquired a massive amount of ‘underground laboratory’ data through our WellCon center during the early infill drilling and completions in the STACK and Delaware basins,” he explained. “The learnings from these projects are now being applied through new fracturing designs in the Powder River Basin program. An example is how Devon has integrated the data from all our basins to build custom applications that predict fracture interference with parent wells. This tool is improving the economics of all our development drilling through advanced stimulation designs.”

Meanwhile, Anadarko, the fourth big independent with a major position in the basin, is also sitting on a bounty of newly acquired acreage there, focusing on the Turner, and taking a methodical approach. The company, which is building a large inventory of state drilling permits, said in its second-quarter earnings report that it has developed a play concept for the Turner, where some of its wells have produced more than 2,000 BOE/D with an oil cut of more than 80%.

“Our thoughts are, as we complete our appraisal work and look at a development plan … we think this has a really important role in the future for what we’re going to put capital toward,” said Robert A. Walker, Anadarko chairman, president, and chief executive officer.