The Pikka Field discovered by Armstrong Oil & Gas is just 2 to 3 miles wide, about 30 miles long, could produce 1.2 billion barrels of oil, and is one of three major finds that have shattered assumptions about what is possible in the most explored parts of Alaska’s North Slope.

“The Armstrong discovery, and especially the size of that discovery, was stunning to everyone,” said David Houseknecht, a geologist for the US Geological Survey who has done multiple assessments of the potential in the area. “The thinking was the biggest oil pool we could imagine had 200 to 250 million barrels of recoverable oil. These discoveries coming in with more than a billion barrels or 300 million barrels, at least, really change things by an order of magnitude.”

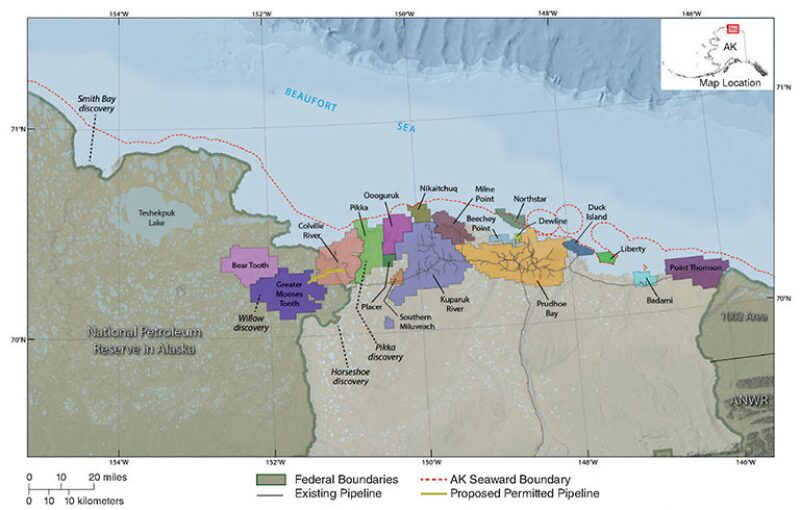

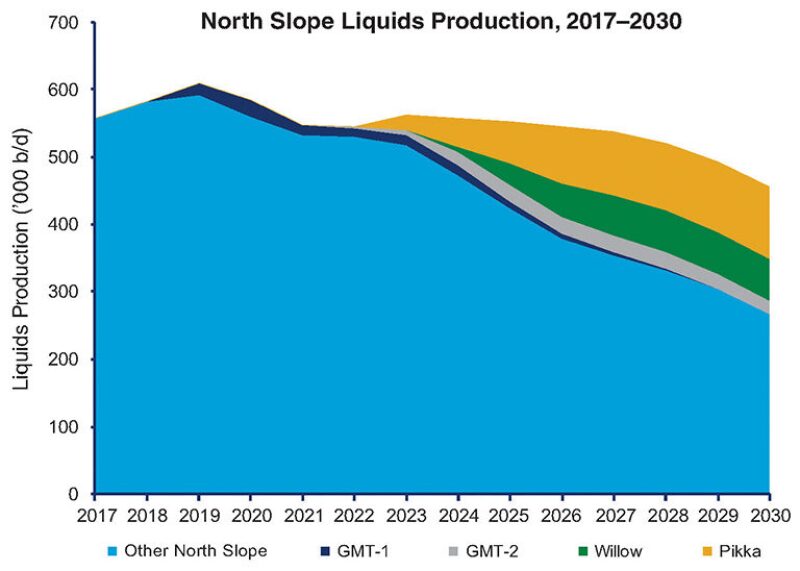

The find by Armstrong in March may not be the biggest of the three. A discovery by Caelus Energy in Smith Bay called Tulimaniq could produce twice as much oil though the development challenges are also much greater. And ConocoPhillips’ Willow discovery could ultimately produce from 3.3 to 3.9 billion, and add more than 400,000 B/D of production in the next decade.

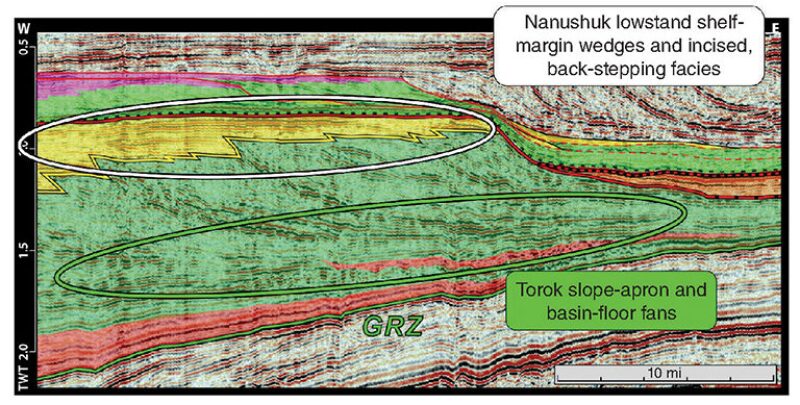

It is an impressive total, even when discounted for the fact that these are early estimates in a costly area for development in a period of struggling oil prices. In addition, what has been learned about identifying the subtle signs of oil trapped within two large formations—the Nanushuk and the Torok—could open up greater opportunities.

The recent finds could turn the Nanushuk from a minor reservoir into a “virtually unexplored play fairway covering at least 9000 to 15000 km2 that includes both onshore and shallow offshore areas,” said Houseknecht. He made the comment during a presentation at the recent annual meeting of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists in Houston, where even poster sessions on the North Slope drew crowds.

Those finds highlight advances in the tools used to look for oil pockets trapped in the earth, and unconventional techniques needed to maximize production from conventional reservoirs that are tighter than the free-flowing reservoirs found in the aging Prudhoe Bay field to the east.

“The bottom line is, because of 3D seismic and because of the completion practices used for unconventionals, we can now reasonably look at low-permeable Brookian [Nanushuk and Torok] reservoirs as viable,” he said.

One sign of the industry’s confidence was bidding at state and federal lease sales in December, where ConocoPhillips was the most aggressive bidder, picking up about 600,000 net acres, said Alison Wolters, a research analyst for Wood Mackenzie.

Analysts for Wood Makenzie set the break-even oil price needed to profitably develop the Pikka and Willow projects at USD 50/bbl and USD 55/bbl, respectively. There are other barriers, though, to North Slope development.

“It is not just about the break-even. These are not cheap projects; they are multibillion-dollar projects. The smaller companies need to find partners to spread some of the risk. That is not easy,” said Imran Khan, senior research manager for Wood Mackenzie. “The infrastructure has to be there. Partners have to be there. The state has to have its fiscal act together. A lot of things have to be in place.”

Unrealized Potential

A 1979 USGS report said the Nanushuk could become a “major hydrocarbons play” in the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska but, in the decades that followed, companies met mainly frustration.

Wells penetrated the Nanushuk about 150 times on the way to deeper targets, and only one discovery was made and produced, Houseknecht said. That small pool was developed within ConocoPhillips’ Alpine field, where large oil reservoirs in deeper Jurassic horizons covered the cost of the infrastructure.

The recent discoveries in the Nanushuk were hard to find because these reservoirs are narrow targets. They are wedges of sand deposited along narrow coastal beaches and deltas, constrained by land and sea, and can be from 150 to 250 ft thick.

The discoveries became visible as companies such as Armstrong, a small Denver independent led by its founder and chief executive officer, Bill Armstrong, figured out how to spot traps using 3D seismic and imaging methods to highlight likely reservoirs.

In an interview with the Alaska Journal of Commerce, Armstrong said the work leading to the discovery began with buying “tons of seismic data” covering 500,000 acres, and then deliberately searching for stratigraphic traps.

It is a difficult process because the stratigraphic traps with the oil are in sand deposits that are difficult to detect even in the most detailed 3D seismic images, and surface features offer no clues that they are below.

“Like what we had found the other times it was not our primary objective. It was a secondary objective and it was almost invisible on the seismic, so you can see why everybody missed it,” Armstrong said in the interview.

The northern part of the field was found in 2011 by Armstrong and its partner Repsol at about 4,000-ft depth. Two wells drilled this year extended the field 20 miles to the south. As a result, explorers have confirmed what sort of geological features are likely to hold oil, and have set up their seismic imaging systems to highlight those possibilities.

“I have seen Armstrong 3D images,” Houseknecht said. “They have figured out how to make it light up.”

Based on the recent discoveries, which suggest “dozens of prospects to test,” he made a successful pitch for the USGS to update its assessment of the Nanushuk and Torok, and now he is looking for low-cost sources of 3D seismic, particularly surveys subsidized by the state of Alaska, which will be made public soon.

While federal agencies that engage in leasing, such as the Bureau of Land Management, are given access to 3D seismic, they are not allowed to share it with the agency whose assessments are aimed at aiding those seeking exploration targets.

While he said they do get looks at other people’s seismic, what they are studying on their desktops is often older surveys showing only 2D cross-sections of the subsurface. On 2D, “it is virtually impossible to see [traps],” Houseknecht said. “These are very subtle features ... It is way too risky drilling on 2D alone.”

Realizing Potential

Discoveries holding billions of barrels of oil invite comparisons to the giant Prudhoe Bay field, which are not very flattering. Comparing recent discoveries with a world-class reservoir that has produced 14 billion bbl of oil to date shows why it is getting harder to find and produce oil.

Given the scale of the Nanushuk and Torok plays, it might rival it someday. “Maybe taken as a whole, the entire plays across the North Slope could be that big,” Houseknecht said, adding, “But it is not 15 billion barrels of recoverable oil concentrated in one pool.

“These reservoirs are hugely different than the main one in Prudhoe Bay,” he said. There the reservoir was made up of coarse-to-medium sands to conglomerate, with little cementing to block the flow. In that reservoir, the permeability was measured in darcies.

Recent finds have been in tighter rock, ranging from hundreds of millidarcies in the Nanushuk down to tens of millidarcies in the Torok, which is deeper and tighter.

While wells in the Pikka field could be developed in a conventional way, Houseknecht said it is likely to be developed using long laterals and lateral injection wells like those in ConocoPhillips’ Alpine field to maximize output.

The Smith Bay discovery is in the Torok, where Caelus will likely need to fracture the formation to generate enough production of the ultralight crude, he said. On the plus side, the private company has experience with lower-permeability production on the North Slope, and there is a huge amount of oil under Smith Bay to justify the investment.

At this early stage, Wood Mackenzie has not estimated the break-even cost of development in Smith Bay because of the lack of appraisal information, Wolters said.

Building the infrastructure for the Prudhoe field was simple compared with the developing fields scattered over the harsh, environmentally sensitive Arctic environment.

Pikka has a pipeline running through it, and Willow is building a short line running past two earlier finds, but Smith Bay is about 125 miles from the nearest pipeline connection, she said.

The obvious onshore route to Smith Bay is off limits to development because it would go through land around Teshekpuk Lake, which is environmentally sensitive and relied on by native peoples for subsistence, Houseknecht said.

The likely solution would be constructing a buried pipeline in the shallow coastal waters from Smith Bay to Caelus’ Oooguruk Field, where it could be tied into a line feeding the Trans-Alaska pipeline.

The discoveries come at a critical time for the North Slope, whose link to export markets has been the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System. Without the volumes from these fields coming on line in the next decade, the flow through the aging line was expected to drop below the level needed to justify the cost of keeping it operating.

Falling production and low oil prices have also blown a hole in the state’s budget, which depends on oil industry revenues. To fill that gap, Alaska’s legislature is considering an oil industry tax increase for the second year in a row.

“We will see what happens,” Wolters said, adding, “It could be difficult to plan development and secure capital when there is so much volatility in the fiscal environment.”

Pikka

Discovery: 2011 and extended in 2016

Companies involved: Armstrong Oil & Gas (operator) and Repsol

Estimates: 1.2 billion bbl of recoverable oil

Formation: Nanushuk

Pipeline connection: Yes

Terrain: Onshore

Highlights: 120,000 B/D production planned by 2021

Links: Repsol press release

Tulimaniq, Smith Bay

Discovery: 2016

Companies involved: Caelus Energy (operator), NordAq Energy, and L71 Resources

Estimates: 1.8–2.4 million bbl recoverable, and 6–10 billion bbl oil in place

Formation: Torok

Terrain: Shallow offshore, with water depth of around 10 ft

Pipeline connection: No

Highlights: Could produce 200,000 B/D of light oil (40–45 °API)

Links: Caelus release, fact sheet, Images

Willow

Discovery: 2016

Company: ConocoPhillips

Estimates: Could produce 300 million bbl of light oil (early estimate)

Formation: Nanushuk

Terrain: Onshore at Greater Mooses Tooth area in National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska

Pipeline connection: Under construction, 28 miles from ConocoPhillips’ Alpine Field

Highlights: Production of up to 100,000 B/D by 2023 of light oil and condensate, plus 30,000 B/D under development nearby

Links: ConocoPhillips press release