In recent years, offshore projects have increased in size, scope, and cost, expanding into deeper waters and new frontiers. Alongside this growth, the negative potential for nontechnical issues relating to health, safety, security, environment, and social responsibility (HSSE-SR) on a project’s timeline has also increased. Projects are under more intense scrutiny from the companies that own and operate them.

In an effort to better understand the value of nontechnical risk (NTR) at the project and portfolio level, companies are searching for the proper systems and processes to deliver quality HSSE-SR performance. The elements of NTR assessment, the methodologies of managing NTR, and how they relate to offshore projects will be examined.

NTR Integration

Companies are spending more time exploring potential NTRs in depth, and the heightened knowledge of NTRs has had a visible impact on operational and functional project development. They are also exploring a wider range of nontechnical topics, particularly in anticipating the needs in local workforce availability across their development portfolios for both employee and contracting requirements (Brewer and McKeeman 2012).

Linda Brewer, a senior partner at Environmental Resources Management (ERM), said that nontechnical issues pose a greater threat to upstream projects than mid- or downstream projects because organizations face a greater number of unknown factors with regard to design and field context. Both midstream and downstream activities typically involve the use of familiar resources, such as the construction of a pipeline along an existing pipeline or production from an existing facility.

“I think it’s the decision-making process in upstream more so than downstream because of the different stage gates,” she said. “If you’re going into virgin territory, for example, then the risk can be significant to the billions of dollars being invested. Usually, when you’re midstream or downstream, there’s enough stability to where there’s not going to be a significant concern of a lump financial impact.”

Because of their size, smaller companies will sometimes examine the net present value (NPV) potential of a project but not take as deep of a look at the risk potential. For example, a larger company may have a staff devoted to environmental factors, thus allowing the screening for risk potential early in the life cycle of the project. With fewer resources at their disposal, smaller companies may not be able to afford an exhaustive screening process.

“If you are a company that is small and nimble, you may not invest in some of the environmental, social, or other risks early on because it doesn’t make sense; you’re just trying to see if there’s the possibility of a deal here and not put a lot of money up front before you know you have a deal. Sometimes that pays off. Sometimes it does not,” Brewer said.

NTR performance requires the acquisition of data from various sources, consolidation and analysis of the data, and implementation of the analysis in everyday practice. Asset managers need an oversight on emerging HSE issues that may affect a project’s schedule or cost. Technical experts must incorporate stakeholder requirements into the project’s design, and the leadership must identify issues before they spread across geographies and portfolios.

A metric tracking system could help organizations identify the connection between NTR and technical risks. This connection may include technical solutions to nontechnical problems, such as developing a traffic plan to minimize the noise and traffic congestion in a community near a fabrication yard. It may also include nontechnical solutions to technical problems, such as preventing microorganisms on foreign-built vessels from entering a domestic ecosystem.

Brewer and McKeeman discussed a framework for a system that integrates four key elements of metric tracking: business value drivers, internal readiness and alignment, external sensing, and management actions and resourcing.

The system includes

- A yardstick that represents the performance continuum as related to nontechnical categories, such as HSSE-SR or stakeholder engagement

- A maturity model that helps organizations develop their practices and can be adapted for use in other areas, such as human resources and safety culture

- Evidence-based management that explicitly uses the best current evidence for decision making

Outside Voices

One developing trend in the industry is the partnership of operating companies with outside consultancy groups to mitigate NTR on exploration and production projects. An NTR consultancy differs from an HSSE-SR consultancy in that the former looks at the soft issues of NTR in an integrated fashion (Brewer and McKeeman 2012). The value of an operator working with a single consultancy outweighs the cost of educating the consultancy about its control and management systems and organizational requirements.

Brewer said there are benefits to a company involving an outside entity such as a contractor, nongovernmental organization, community representative, or a government agency in NTR planning and prevention. An outside entity can act as a neutral voice that carries weight with different factions that may be at odds over how to proceed with a project. It can also help validate a project with community stakeholders on a social level.

However, the extent to which outside entities can positively affect NTR planning depends on several factors such as the values of the operator, its core competencies, and the types of projects that the operator seeks.

“Having that sort of outside source, we see sometimes the communication is better, or sometimes the standardization of some processes—like a permitting process within the Gulf of Mexico—can be more efficient because you have that outside person and that’s all they do. Sometimes having that third party outside of the political context of the organization is helpful. The politics become a little less intense,” Brewer said.

Outsourcing the process of identifying and mitigating NTR completely is an alternative that more companies are considering, though it is still rarely done in the industry. Outsourcing usually involves putting a representative from an outside consultancy onto the leadership team for a particular project, which allows the consultancy to work closely with the technical risk team during the project’s life cycle while assuring the plan’s integrity.

Scott Nadler, a senior partner at ERM, said an outside source is only valuable if a company takes its advice seriously.

“These entities can have great insight, knowledge, access, and credibility," he said. "Listening to them is a great way to learn and anticipate. The challenge is that you actually have to listen to them. You can’t just tick the box and say, ‘Well, we talked to them.’ Did you ask the right questions? Did you hear the answers? Did you do anything differently based on them?”

Neutral voices are important for managing what Brewer called the “perception of credibility” both inside and outside of an organization. She said perception risks from the outside are a greater threat because of the speed with which information travels online, but a negative perception from inside can lead organizations down a disadvantageous path.

Any instance of misalignment within an organization is an opportunity for a misstep and it is important to limit those possibilities, Brewer said.

“If I’m on the project team, I understand my impact on risk and my ability to decrease risk,” she said. “If I’m [human resources] and I hire the right people or the wrong people, then I’ve got an impact on risk. If we are truly talking about cross-functional projects, then we’re going to be healthier as a result.”

Brewer and McKeeman said that the best way for organizations to deliver projects on time and under budget is by establishing clear strategic business objectives; however, too many organizations are plagued by fragmentation in this area, particularly across specialties. On the nontechnical side, fragmentation often comes with overlapping goals and boundary confusion. The latter often spills over into the project, leading to inefficiencies in execution.

In addition, the integration of lessons learned from previous projects into project methodology, and the real-time sharing of emerging research, can help optimize organizational structures. Organizations rarely take the time to document the improvements made with NTR processes and teach those improvements, and paying systematic attention to lessons learned can build the quality of project processes and potentially improve a project’s NPV.

Brewer said that while some companies are better than others in taking the time to look at lessons learned, these are typically among the first items cut when a project team is pressed for time or money. Because the industry relies heavily on technical expertise, technical operations are still a greater priority for some organizations.

“You have to walk a fine line between lessons learned becoming a rule and lessons learned becoming an informed option,” she said. “There is a lot of flexibility in how we can use these lessons. You have environmental support functions. What seat at the table do they have? How are they considered? I have worked with project managers who really value that input and project managers who don’t have the time for that input. It depends very much on how it’s viewed within the individual companies.”

Deepwater Project NTRs

The NTR management of deepwater projects must be considered in the context of the project’s location and its scope, which may include the reservoir, wells and completions, production host, subsea equipment and flowlines, pipelines, onshore facilities, and offshore facilities (Reid et al. 2014).

The physical scope and the nontechnical landscape create the project’s overall context, and it is in this context that the project must be delivered. Projects in which the management team considers the overall context are most likely to succeed.

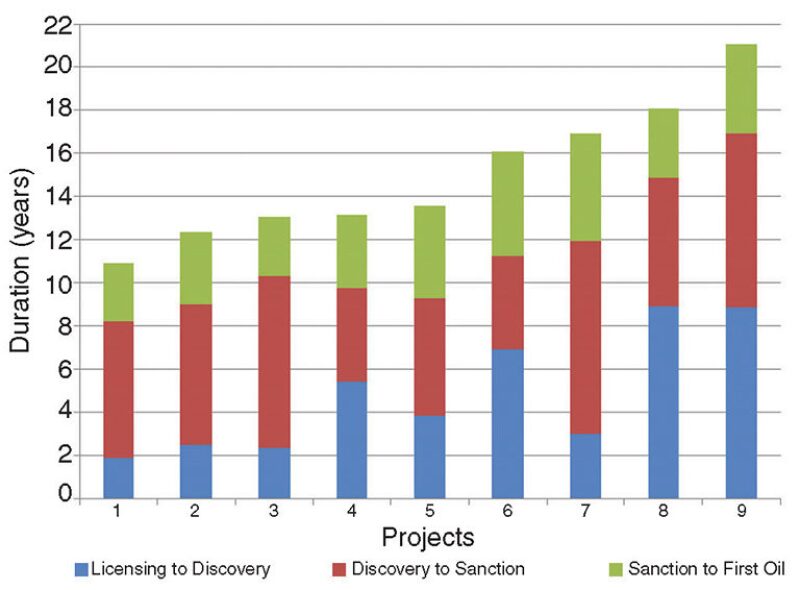

NTRs may arise and affect any phase of a deepwater project, and their impacts may vary wildly in severity (Fig. 1). Nontechnical issues that happen earlier in a project’s life cycle typically result in delays to major project decision stage gates, affecting the internal view of a project. Nontechnical issues that happen in the middle stages of the life cycle may have a more significant impact on the schedule, sanction date, and cost.

But the most significant impact comes from nontechnical issues that arise post-sanction, during the execution phase. Because owners are spending the most capital and the project’s visibility is at its highest point in this phase, errors that occur during execution may not only have a major cost impact, but they may also negatively affect the reputation of the owner and the operator.

Nadler said that a company’s goal with any project is to improve at spending the money needed to reach its optimal outcome. It requires anticipating potential problems, understanding them, and handling them long before they arise.

“The key is remembering that it’s all about the outcome, which only happens later in the life cycle,” he said. “You can spend a lot of money, but you don’t make money unless you get pretty far in the project life cycle with the right pieces coming together. Nontechnical risks are the issues that can most keep those pieces from coming together successfully.”

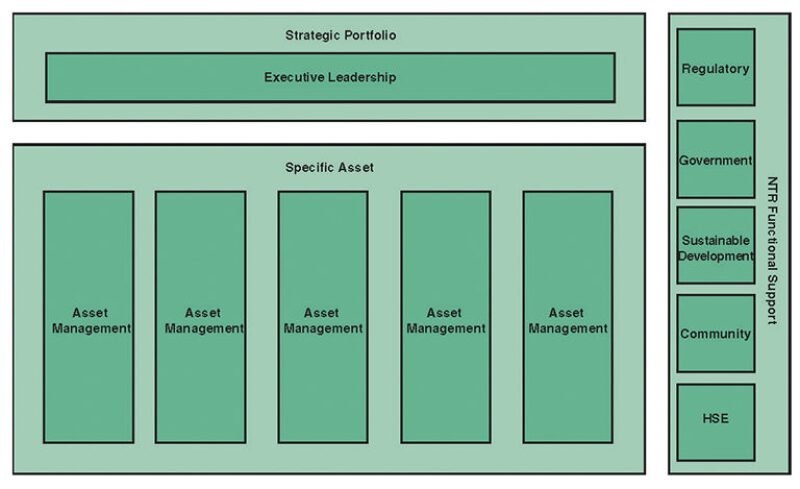

The idea that NTR assessment of any major capital project, deepwater or otherwise, should begin early in the project’s life cycle is not new. Brewer and McKeeman also argued that starting the process early, preferably in the prelease or concept phase, is an optimal course of action. They said that organizations should strive to boost nontechnical performance at three levels in the project:

the strategic portfolio level, the specific asset level, and the NTR functional support level (Fig. 2).

“It’s a serious amount of money, so how much do I want to look at [NTR]? If it were my money, I would always start early. I would want to know that I’m not going to have something that has zero return or that the [NPV] that I’ve promised my investors is going to be way off,” Brewer said.

The deployment of NTR research early in a project’s life cycle can help an organization build a more pragmatic view of the potential for nontechnical incidents. This may save months and even years as opposed to late-life NTR research, but it is a difficult balance to strike. Waiting until the last minute to work on NTR mitigation may lead to severe negative consequences for a project. On the other hand, starting the assessment too early on a project with limited NTR risks may lead to unnecessary procedural delays.

Reid outlined a process for the early incorporation of the assessment of NTR as it relates to a deepwater project’s cost, schedule, and value. The first step is to define the scope of a number of concepts for the development prior to concept selection. The second step is for management to work with its technical and functional support teams to develop a structured process that identifies the nontechnical issues, possible triggers, and impacts to a project.

In the third step, the management team devises a project cost estimate and an interlinked project schedule after the NTR identification process has been developed. The cost estimate should map the nontechnical issues against the cost, and the schedule should take into account nontechnical activities and their link to technical scope. These activities could be permits, approvals, new legislation, or local content requirements.

The fourth step in the process is to connect any identified NTRs to the project cost and schedule estimates and, using a project planning software program, play out the probabilities and potential impacts of each NTR.

In the fifth step, the management team reviews the impact of nontechnical issues on cost estimates and major project milestone timing by examining the interplay of nontechnical issues and the changes in the project’s life cycle in each scenario.

Reid said this was one of the most overlooked areas of NTR management. As an example, he described the implementation of this process in an unnamed deepwater project with an export pipeline to shore. The management team developed a detailed schedule which showed that the project’s critical path, or the sequence of schedule activities that determines the duration of the project's life cycle, was driven by the construction and installation of the

host structure.

By applying the NTR testing process, the team determined that three low-impact nontechnical permitting approval issues could affect the scope of the pipeline and onshore operations. As a result, the managers shifted the project’s critical path activity away from the pipeline construction, thus allowing the project team to speed up the permitting process.

In the last step in the NTR process, the operator updates its management and mitigation plans. These updates may include changes to the scope of the project.

Reid also proposed a framework for NTR management strategies as a function of the risk profile of a project’s location and the NTRs unique to that project. The lower the location risk, the easier the NTR management becomes for implementation by an operator, because its strategy can be more project-focused.

The strategies were divided into four categories:

- Business as usual. Projects with limited project-specific NTRs in a location with low risk require less time and fewer processes and resources being devoted to NTR management. Although a low risk does not mean zero risk, operators must be aware that small nontechnical issues could adversely affect their projects. However, dedicated project management resources are unnecessary. Any deepwater project in the US Gulf of Mexico would be an example. Reid listed the Shell-operated Perdido platform as a project that followed this specific strategy.

- Project-dedicated NTR plan and team. A project-dedicated NTR plan and team is recommended for projects with significant project-specific NTRs located in a relatively stable environment. In these situations, managing the project-specific NTRs would take up a considerable amount of the team’s time, and should the NTRs not be managed effectively, they would prove to be a difficult obstacle in executing a technically sound project. The NTR plan and team must be fully integrated into the overall project plan, and the project manager is fully accountable for nontechnical issues. Shell’s Ormen Lange gas field in the Norwegian Sea followed this approach. The deepwater project has a large onshore project scope operating in a stable environment.

- Location of NTR plan and team. For projects with limited project-specific NTRs located in high-risk locations, operators should have an NTR plan and team at the country or regional level to handle local nontechnical issues. The team would help to establish a stable external environment so that the operator may proceed with its development strategy. The NTR team should stay to monitor and mitigate location-specific issues that may arise as the project proceeds toward sanction. This strategy typically applies to projects with an established support infrastructure and benign geographic conditions in areas with complex and unstable regulatory atmospheres or political regimes.

- High stakes engagement. This strategy is suitable for projects with high project-specific NTRs located in high-risk environments. Projects of this nature typically require a significant investment in capital and resources, and they are expected to bring in a large return on the investment. These projects need the joint efforts of a dedicated country-focused NTR team and a project-specific NTR team. The direct engagement of senior and executive company management must supplement the efforts of both NTR teams along with high-ranking officials in various stakeholder organizations such as a local government or a regulatory agency.

For single-string ventures or ventures in which an individual project is a company’s only asset at a given location, operators may potentially use a strategy suitable for projects in low-risk locations. However, this strategy is not an optimal one (Reid et al. 2014).

For Further Reading

SPE 157575 Non-Technical Risk Leadership: Integration and Execution by L. Brewer and R. McKeeman, ERM.

SPE 170739 Deepwater Development Non-Technical Risks—Identification and Management by D. Reid, Shell Upstream Americas; M. Dekker, Shell International;A.H. Paardekam, Shell Brasil; et al.