MARCELLUS SHALE: LIQUIDS-RICH OR DRY GAS?

The Rise in Marcellus Liquids

Ever since its pioneer Renz No. 1 well, recompleted to target the Marcellus shale in October 2004, Range Resources has led trends in the play’s activity. If this holds true, the Marcellus is in for a surge in liquids-rich development.

The company says it is devoting 79% of its 2013 USD-1.3-billion capital budget toward development drilling in the Marcellus shale region. A total of 85% of this spending is being directed toward liquid areas, and 82% of the budget is focused on drilling.

Range states that the “large, liquids-rich window in southwestern Pennsylvania” is the reason “the Marcellus offers the best economics of any large-scale, repeatable play in the country.” The company’s exploitation of this liquids-rich area is well under way. During the first 6 months of 2012, Range produced most of the unconventional gas condensate in Pennsylvania—566,631 bbl—all in Washington County. It almost doubled that production in the latter half of 2012, with 1.1 million bbl, again all in Washington County.

Range has worked steadily over the past 9 years to define the productive limits of the Marcellus. The company believes the industry has achieved this goal through drilling approximately 1,650 wells (1,150 horizontal and 500 vertical). Range says it has drilled 570 wells (511 horizontal and 59 vertical) in the southwest portion of the play. About 110,000 acres of Range’s position in southwest Pennsylvania is prospective for what it calls “super-rich” Marcellus, 220,000 acres for wet gas, and 210,000 acres for dry gas.

Only a handful of other companies have met with success when drilling for Pennsylvania Marcellus liquids—and most production has been moderate to negligible. These include Shell (through SWEPI LLC), Chevron, and ExxonMobil (through XTO), as well as a sprinkling of smaller companies like R.E. Gas Development (a subsidiary of Rex Energy), BLX Inc., Triana Energy, and Northeast Natural Energy. The liquids-rich play is growing in activity in northern West Virginia, with several operators such as Chesapeake, EQT, Stone Energy, Anterro, and Gasstar expanding drilling efforts there.

Sustaining Dry Gas Production: Learning By Doing

Faced with a glut in the US of dry natural gas that keeps Henry Hub Natural Gas Spot prices hovering around USD 3.63/MMBtu, there is a general trend throughout the country away from dry natural gas drilling to liquids-rich plays. And while liquids exploitation is enticing because they command higher prices, they also represent a challenging logistical conundrum. Infrastructure must be in place to transport and process the liquids.

However, demand for dry natural gas [mostly methane (CH4)] continues unabated, with nationwide 2012 consumption reaching 25.5 Tcf (around 69.67 Bcf/d). So far this year, nationwide natural gas production has averaged 65.87 Bcf/d, according to US Energy Information Administration (EIA) statistics.

Pennsylvania is supplying more than 9% of US consumption needs (see sidebar). This is due to natural gas production (including both conventional and unconventional sources) that averaged 6.1 Bcf/d in 2012, up 69% from 3.6 Bcf/d in 2011—largely from Marcellus wells. This increase occurred despite a drop in the number of new natural gas wells started in the state during the year. According to the EIA, “The increase was largely due to a backlog of wells that had been drilled before 2012 but not brought on line because of infrastructure constraints.”

Another factor the EIA cites for Pennsylvania’s success is the effective use of technology in increasingly geologically favorable portions of the Marcellus. “As operators continue to improve well completion techniques,” wrote the EIA in late March, “they are achieving higher initial per-well production rates and boosting overall production.”

This type of on-the-job learning is driving many companies active in the dry gas Marcellus play, despite lacking the freedom to absorb the bottom-line impact of dry-well experimentation. This means smarter drilling to ensure costs can be recouped, with some margin for profit.

So not only is Marcellus gas tight, so are its economics.

“There are maybe a handful of companies that are profitable with wellhead prices at USD 3.5/Mcf,” said Kelly Whitley, director of investor relations at Ultra Petroleum. In a recent presentation, the company cites USD 1.52/Mcfe as the finding and development cost for its Pennsylvania Marcellus wells. Ultra says it is in the early stages of Marcellus development, with a total of around 260,000 net acres located in what Range is identifying as a Marcellus dry gas window in the northeastern part of Pennsylvania.

Range has also experienced considerable success drilling unconventional dry gas wells. Its Pennsylvania Marcellus dry gas production has risen steadily from 34.6 Bcf during the 12-month period from July 2009 to June 2010, to 111 Bcf during the latter half of 2012. The company also, according to a Bank of America study, has achieved the position of first, second, or third low-cost producer for each of the last 9 years (#1 in 2012). “Unit costs are a key focus,” Range says, with a steady 30% decline in unit costs—from USD 4.30 in 2008 to USD 3.00 in 2012.

Another company with notable dry gas success is Cabot Oil and Gas. “The success of our drilling program in the Marcellus continues to drive record operating and financial metrics for the company, including all-time highs for quarterly production, revenues, operating cash flows, and discretionary cash flows, despite historically low realized natural gas prices,” said Dan O. Dinges, chairman, president, and chief executive officer. Total per-unit costs (including financing) decreased to USD 3.29/Mcfe in first‑quarter 2013, down 15% from USD 3.85/Mcfe in first‑quarter 2012. “Gross Marcellus production during the first quarter of approximately one Bcf per day, resulted in double‑digit sequential production growth rate for the quarter,” commented Dinges. “As additional infrastructure projects throughout our Marcellus position come on line during the year, it will afford us further increases in production.”

Pennsylvania Turns Unconventional

Dry Gas or Not Dry Gas?

So, despite the liquids-rich possibilities, the Marcellus is still yielding mostly dry gas. Many companies are focused on that goal, eschewing the challenging entry into the process of building, acquiring, or entering agreements involving cumbersome midstream liquids gathering and processing infrastructure.

For example, Calgary, Alberta-based Talisman Energy has grown its acreage’s dry gas production fairly steadily since it first established a position in the area in 2009, with Pennsylvania Marcellus production during the 12-month period from July 2009 to June 2010 at 30.7 Bcf. During 2012, annual production reached almost 400 Bcf. Talisman’s 208,000-net-acre position, largely in the dry gas northeastern part of Pennsylvania, exists within a much broader asset context than Range’s. Its two stated core areas are North America—including Montney, Duvernay, Edson, and Eagle Ford acreage in addition to its position in the Pennsylvania Marcellus—and Asia-Pacific.

Cabot, another company whose Marcellus success has been widely touted, has trended upward, too, in natural gas production—its Pennsylvania Marcellus wells yielded 26.8 Bcf during the 12-month period from July 2009 through June 2010, and in 2012 yielded 242 Bcf. The company has around 200,000 net acres in the Marcellus. Sixty-five percent of Cabot’s estimated 2013 capital program of USD 950 million to USD 1.025 billion is targeted at the Marcellus, with 85% of the budget “focused on the drill bit.”

However, many companies in the Marcellus are showing signs of moving away from dry gas acreage.

The highest Pennsylvania Marcellus gas producer is Chesapeake. In March 2008 it said among its plans were to increase drilling and leasing activity in the Marcellus and Lower Huron shales. The company did just that, steadily ramping up Pennsylvania Marcellus production from 33.8 Bcf during the 12-month period from July 2009 to June 2010 to around 301 Bcf in 2012.

However, on 19 April, Chesapeake and its partners sold natural gas properties to Southwestern Energy for about USD 93 million. The sale amounts to about 162,000 net acres in the Susquehanna, Wyoming, Tioga, and Sullivan counties—in the Marcellus dry gas window. Estimated per-acre price is USD 574. Current net production from the properties is about 2 MMcf/d from 17 gross wells. Following closure of the deal, Southwestern will have about 337,000 net acres in the Marcellus shale.

In addition, on 3 May, EQT Corporation announced it had purchased roughly 99,000 net acres and 10 horizontal wells in southwestern Pennsylvania from Chesapeake and its partners for approximately USD 113 million. EQT says the acreage includes 67,000 Marcellus acres and 32,000 dry Utica acres. The 10 wells are located in Washington County.

In 2010, Shell purchased East Resources, a Pennsylvania company that at the time owned more than 2,500 oil and natural gas wells in the US and controlled 1.25 million acres of land, mostly in the Marcellus shale. Purchase price was USD 4.7 billion. During July 2009 through June 2010, East’s 28 Pennsylvania Marcellus wells produced 10.2 Bcf. Shell’s SWEPI has kept a low profile in the Marcellus, and in 2012 produced 93.5 Bcf in Pennsylvania, the vast majority from Tioga County.

However, in mid-April Shell and Williams Partners created a midstream joint venture—Three Rivers Midstream—whose purpose is to serve Shell and other producers in the wet-gas areas of the Marcellus and Utica shales. Three Rivers will provide gas-gathering and gas- processing services to production located in northwest Pennsylvania. The venture will invest in both wet-gas handling infrastructure and dry gas infrastructure.

Three Rivers signed a long-term fee-based dedicated gathering and processing agreement for Shell’s production in the area, including around 275,000 dedicated acres. Three Rivers also plans to construct a 200-MMcf/d cryogenic gas-processing plant and related facilities. With location undetermined at present, the initial plant is expected to be placed into service by second-quarter 2015.

“The system is expected to be connected to two major proposed developments in Pennsylvania,” said Alan Armstrong, CEO of Williams Partners’ general partner, “—Shell’s proposed ethylene cracker (feasibility still being studied) in Beaver County and the proposed Williams/Boardwalk joint venture to develop the Bluegrass Pipeline system (target in-service date late 2015) that would deliver Marcellus and Utica liquids to the rapidly expanding Gulf Coast and export markets.”

Chevron Appalachia purchased Atlas Resources in 2010 for USD 3.2 billion, thereby acquiring 486,000 net acres of Marcellus shale and 623,000 net acres of the closely aligned Utica shale. The company also acquired 228,000 net leasehold acres in the Marcellus shale from Chief Oil & Gas and Tug Hill for an undisclosed amount in mid-2011. It would appear that, through the Atlas subsidiary, Chevron is producing some condensate in the Pennsylvania Marcellus—a total of 43,848 bbl in 2011—and 41,018 bbl in 2012.

THE MARCELLUS: FROM SOURCE ROCK TO RESERVOIR

Why did Range become interested in the Marcellus in 2004—4 years before the boom began—when no other company appeared to be paying attention to it? The decision to target the Marcellus came at a time when its potential was a matter of wide speculation and stemmed from the company’s strategy shift in 2000 away from “acquire-and-exploit.” Instead, it began to foster a more technical, long-term perspective woven into daily operations through low-cost, consistent growth in production and reserves.

Two men who helped drive the company’s approach were its president and chief executive officer, Jeffrey L. Ventura, and William A. Zagorski, Marcellus Shale Division vice president of geology. In fact, in 2009, the Pittsburgh Association of Petroleum Geologists honored Zagorski’s key role by officially giving him the title “Father of the Marcellus.” And this year he received the Norman H. Foster Outstanding Explorer Award from the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG) at AAPG’s annual convention in May, given “in recognition of distinguished and outstanding achievement in exploration for petroleum or mineral resources, by members who have shown a consistent pattern of exploratory success.”

The Journey Begins

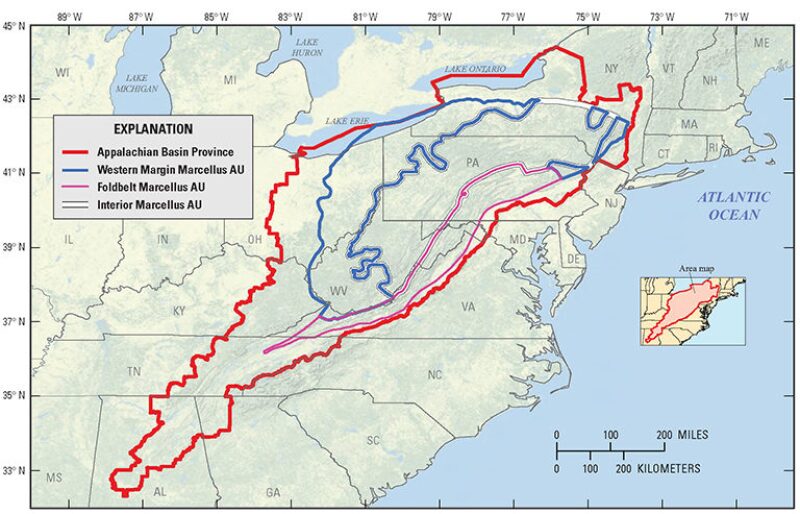

The Marcellus is a formation found within the Appalachian basin province, which comprises a total petroleum system (TPS) that extends generally from New York to Tennessee. The Devonian shale/Middle and Upper Paleozoic TPS has produced a large proportion of the conventional oil and natural gas discovered in the Appalachian basin since the milestone Drake well was drilled in Pennsylvania in 1859.

According to a historical overview of the Marcellus shale play in Pennsylvania, by J.A. Harper (Pennsylvania Geological Survey) and J. Kostelnik (Weatherford Laboratories), “Many people believe that gas from shales is a new phenomenon. In fact, the first gas well in North America was a shale gas well, initially completed 38 years before ‘Colonel’ Edwin L. Drake drilled his famous oil well in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in 1859.”

The overview points out that shales were “virtually ignored by the commercial oil and gas industry in Pennsylvania until the 1930s.”

In 1930, large amounts of natural gas were discovered in the Lower Devonian Oriskany sandstone in Steuben County, New York. This prompted a flurry of drilling in nearby Tioga County, Pennsylvania. While vertically drilling for the deep gas in the Oriskany, operators often encountered large flows of gas when they penetrated the Marcellus shale, which lies a little above the sandstone and acts as the Oriskany’s cap rock. However, generally after a few hours or days, the flows petered out. The Oriskany gas boom lasted through World War II and into the early 1950s.

Geology, Tax Incentives, and Deregulation

From 1976 to 1992, a multistate program called the Eastern Gas Shales Project (EGSP), under the auspices of the US Department of Energy (DOE), conducted a series of studies to evaluate the gas potential of and to enhance gas production from the Appalachian, Illinois, and Michigan basin organic-rich black shales.

The purpose of the EGSP program was twofold: to determine the extent, thickness, structural complexity, and stratigraphic equivalence of all Devonian organic-rich shales throughout the basins; and to develop and implement new drilling, stimulation, and recovery technologies to increase production potential. A further goal was to generate numerous cross-sections, maps, and technical reports related to the entire Middle and Upper Devonian sequence in western and north-central Pennsylvania.

The EGSP identified three major and three minor black shale facies in Pennsylvania—major: the Huron, Rhinestreet, and Marcellus; minor: the Pipe Creek, Middlesex, and Geneseo/Burket. However, while these Devonian organic‑rich shales had the potential to be important gas reservoirs, until success with the Barnett shale in Texas started to emerge in the 1990s, it was neither economically nor technically feasible to even consider realizing that potential.

Almost paralleling the EGSP program was the institution—from 1980 to 1992—of the Alternative Fuel Production Credit of the US Internal Revenue Code (an income tax credit). Among the goals of the Windfall Profit Tax (WPT) Act of 1980 was to provide an alternative (unconventional) fuel production credit.

According to a Congressional Research Services Report for Congress (CRS RL 33578), by S. Lazzari (2006), “The 1980 WPT Act included a USD-3.00 (in 1979 dollars) production tax credit to stimulate the supply of selected unconventional fuels: oil from shale or tar sands; gas produced from geopressurized brine, Devonian shale, tight formations, or coalbed methane; gas from biomass; and synthetic fuels from coal.” This credit was in effect for certain types of fuels until 2007, when it expired.

The late 1970s saw another action, which began the process of opening US natural gas markets to deregulation, eventually profoundly affecting how natural gas companies do business. This was at the peak of US natural gas supply shortages, which were largely due to wellhead price controls that had existed since 1954 on natural gas marketed between states. The goals of the Natural Gas Policy Act of 1978 were to create a single national natural gas market, equalize supply with demand, and allow market forces to establish the wellhead price of natural gas.

While the Act took the first steps toward deregulation, it was not until 1985 that meaningful change took place, when Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Order No. 436 was issued, essentially allowing pipelines, on a voluntary basis, to offer transportation services to customers who requested them on a first-come, first-served basis. All the major pipeline systems eventually took part.

What this meant for producers was that now they could sell natural gas anywhere in the nation at competitive prices.

Persistence and Experimentation

Exploring potential through coring and mapping, incentivizing through tax breaks, and deregulating markets are not enough in and of themselves to explain how the Marcellus’ shale gas potential came to be unlocked. It is also a story of persistence and experimentation.

The 1980s and ’90s were also the time when Mitchell Energy & Development’s George Mitchell was experimenting with various permutations of hydraulic fracturing with vertical wells in the Barnett shale.

It took Mitchell 18 years to gradually come up with an economical combination of sand, chemicals, water volume, and pumping pressure for hydraulic fracturing in addition to geologically optimal hole placement. By August 2001, he had achieved such promising results that he was able to sell his company for USD 3.1 billion to independent Devon Energy. The purchase was finalized in early 2002.

Devon is responsible for the insight that led to combining slickwater hydraulic fracturing with horizontal wells in shale oil and gas development.

By 2000, Range had large land holdings in southwestern Pennsylvania, including acreage in Washington County, where the company was initially interested in exploring for gas in the Oriskany sandstone, Lockport dolomite, and Trenton Black River, all deeper targets than the Marcellus shale. The company began to see some results, but was disappointed when its Renz No. 1 well, vertically drilled in 2003 in the county’s Mount Pleasant Township and targeting the Oriskany and Lockport, “was on its way to becoming a pretty expensive dry hole,” said Zagorski. There were significant gas shows, but attempts to complete and commercialize these zones, which were deeper than the Marcellus, failed, and the company decided to plug and abandon the well.

About that time, Zagorski traveled on business to Houston, where a geologist friend, Gary Kornegay, had a prospect he wanted Zagorski to look at in the Neal/Floyd shale in the Black Warrior basin in Alabama. “Part of the prospect pitch included a comparison of the Floyd as an analog to the Barnett shale,” he said.

At that time, Zagorski explained, he hardly knew what the Barnett shale was.

Zagorski, whose career had focused strongly on studying the Appalachian basin, noted that characteristics of the Barnett seemed to parallel those of the Marcellus. “When he showed me all of the information on the Barnett shale,” he said, “it was like, ‘Oh my God.’ We’ve got all this acreage, we’ve got it all right in our backyard in Washington County.”

After getting the green light from Ventura, then Range’s chief operating officer, the company recompleted the Renz Well No. 1 in October 2004, pulling back up to the depth of the Marcellus and performing massive hydraulic fracturing. The results were “reasonable,” according to Ventura (i.e., initial production of approximately 300 Mcf/d, later topping out at 800 Mcf/d).

Range moved quickly to consolidate its land position in Washington County, and other places in southwestern Pennsylvania. The company apparently kept very quiet about its activities. “It was a huge leap of faith for Range to invest almost USD 200 million,” says Ventura in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (20 March 2011). “It was our risk investment before we knew whether it was going to work in a big-time way. For the people that signed up early on, it could have been like the shale plays that failed.”

After drilling and fracturing two more vertical confirmation wells, Range began drilling horizontally in 2005. By early 2006, the team had drilled and completed its first horizontal test well. But the results were not as good as the vertical wells. The second horizontal test came up dry. “The third was twice as good as the first,” said Zagorski, “but still not as good as we needed to establish commerciality.”

With time passing and costs mounting, Ventura still gave support to the project.

Throughout this time, a few other companies, including Cabot Oil and Gas and Chief Oil and Gas, also sought land positions in Pennsylvania. Then, in 2007, Range, having plumbed insights from its first three horizontal Marcellus wells, moved the horizontal section 20 ft higher in drilling its next well, the Gulla #9 well.

Range then drilled three more wells in quick succession, each more productive than Gulla #9. At the end of third-quarter 2007, two wells were placed on line at rates of 1.4 and 3.2 MMcfe/d. During the fourth quarter, three additional horizontal wells were drilled, completed, and tested at initial rates of 3.7, 4.3, and 4.7 MMcfe/d. This was the kind of sustainable commercial success the company was seeking.

On 10 December 2007, Range went public during an investor and analyst call, with the results of the five commercially producing Marcellus horizontal wells. On 17 January 2008, Penn State University issued a press release in which Terry Engelder, professor of geosciences at Penn State, working with Gary Lash, professor of geosciences at State University of New York Fredonia, conservatively estimated that the Marcellus shale contains 168 Tcf—optimistically, 516 Tcf—of natural gas in place, 50 Tcf of which is technically recoverable.

The two announcements drew widespread attention to the Marcellus play and led to a leasing frenzy throughout 2008 and 2009.

In the midst of the frenzied activity, some predicted the Marcellus might become the largest producing gas field in the US. And it did in 2012.

Range has what it had aimed for, a resource play that is highly repeatable and offers large-scale development—the company’s almost mind-boggling Marcellus shale resource share it claims is 26 to 34 Tcfe, with another 12 to 18 Tcfe in the Upper Devonian shales, located above the Marcellus.

Note: Many of the numbers in these articles depend on records maintained on the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection website. Pennsylvania state law mandates that companies report unconventional well results every 6 months. All photos are courtesy of Range Resources.