Following 3 harsh years of budget cuts and layoffs, oilfield services (OFS) companies are beginning to see a recovery take shape. The worst may also be over for heavy-asset suppliers and original equipment manufacturers in the offshore and subsea sector, but most industry analysts believe their recovery will be significantly slower.

The latest financial reports from big-three service companies Schlumberger; Halliburton; and Baker Hughes, a GE company; show an encouraging picture, with orders picking up and results from continuing operations improving.

Amid a growing global economy, demand for oil is increasing while market-balancing supply restrictions led by the Organization of Oil Exporting Countries (OPEC) are supporting the price of oil, which is at its highest level in 4 years. Oil industry capital investment is rebounding, and the shale-driven expansion in North America onshore operations keeps chugging along.

‘Path to Normalized Margins’

In announcing the company’s fourth-quarter and full-year 2017 results, Halliburton President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Jeff Miller said the company “is on the path to normalized margins in North America in 2018” and that the preceding year “marked another step on the road to recovery.”

Similarly, Schlumberger Chairman and CEO Paal Kibsgaard commented as the most recent results were released that “the oil market is now in balance, and the previous oversupply discount is gradually being replaced by a market tightness premium, which makes us increasingly positive on the global outlook for our business.”

The price of international-benchmark Brent crude oil briefly edged above $71 per bbl not long ago, while US-benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude has topped $66 per bbl. Nonetheless, concerns remain over the durability of the supply balance that has lifted the market.

‘Cautiously Optimistic’

“The phrase I would use is perhaps cautiously optimistic about 2018,” said Steve Robertson, head of research for global oilfield services at Westwood Global Energy Group.

The oil downturn, which took the per-bbl price of WTI from $107 in mid-2014 to $26 in early 2016, was as brutal as any the industry has seen and forced structural changes that have set the stage for a different type of recovery. Few industry observers believe that the price will return to a sustained $80 level anytime soon.

“The traditional view is that what goes down has to come up,” said industry adviser Hervé Wilczynski, a principal at EY (formerly Ernst & Young) in Houston. “There was a feeling that you hunker down for a few years and it’s going to come back up. So a lot of the cost reductions were not structural in nature.”

A Different OFS Sector

Operators would get discounts from suppliers. Companies would lay off employees that they often expected to rehire when the cycle ended. “It’s different now because we know it’s not going to come back up,” Wilczynski said. “We’re going to have a different type of OFS sector coming out of this cycle.”

Drilling rig automation, data analytics, machine learning, and digital technology are all designed to take costs out of field processes permanently.

“Rigs are running at half the peak number of a few years ago, and you’re having production increases,” said Boyd Skelton, US operations vice president at Westwood’s Energent Group, speaking of activity in the west-Texas Permian Basin. “The well efficiency has gone up.”

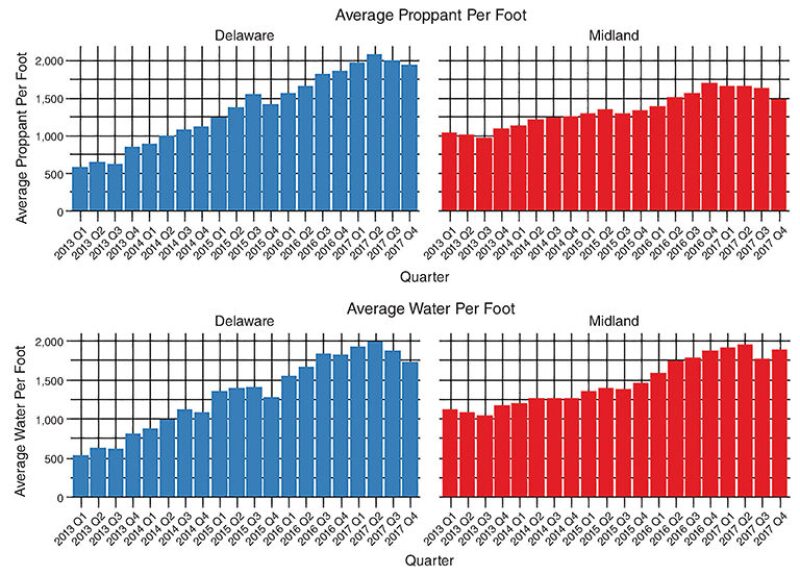

Constant improvement in completion designs has been a key driver of well efficiency, with water and proppant volumes supplied to Permian wells having significantly increased—on a composite and per-ft basis—even as the price of oil declined over the past 3 years. As oil prices have rallied to near-term highs, some proppant providers have seen their margins rise by 30% or 35%, according to Skelton. Regional sand mines in the basin are opening and expanding to help meet the proppant demand.

More broadly in US onshore operations, Westwood expects margins to improve by 15% to 25% this year.

As growth picks up, bottlenecks could become a factor, particularly personnel as workers previously laid off may be reluctant to return.

“I think the people part of the equation has been undervalued,” Skelton said. That could affect pressure pumping operations and their supply chain. “Trucking, last-mile logistics, is a key concern, to be able to get all the equipment, sand, and water to the wellsite,” he said.

The Offshore Story

But if the pace of activity within the onshore US shale sector has returned to growth relatively quickly, it has been a different story for offshore vendors.

Recalling the picture in 2014, Robertson said the offshore sector “had a volume of heavy assets that when we were looking at it at that time we thought was too much, even if activity levels were sustained. But what we saw was a dramatic fall in the oil price and then a very swift move by the E&P companies to cut costs, to stop sanctioning projects.”

By 2016, greenfield projects had slowed to a trickle and not one floating production system (FPS) was sanctioned during the year. In the subsea sector, equipment manufacturers built up huge backlogs before the downturn and have spent much of the time since then working through them.

Subsea Backlogs at Lows

The backlogs are now “at 10-year lows or worse,” Robertson said. “And it’s very difficult to see how [the companies] are going to rebuild them and rebuild activity levels to anywhere near where they were in 2014.”

Nonetheless, he said, “Probably for the first time in a while we’re getting optimistic about the offshore industry.”

There were 15 FPS’ sanctioned in 2017, “and some of the firms are starting to see a lot more FEED [front-end engineering and design] studies,” Wilczyinski said. “We see some investment, starting in the shallow water, the initial kinds of engineering studies for larger developments. Those are leading indicators that the industry has gotten its sea legs.”

Espen Norheim, a partner and an oil, gas, and energy sector leader at EY in Stavanger, said the outlook is “relatively robust” on the Norwegian Continental Shelf and that the country’s extensive offshore service and equipment sector is “very competitive on an international cost basis” for projects globally.

Brazil Decision ‘Bodes Well’

Brazil’s recent decision to allow international companies to operate projects in its offshore presalt acreage is “promising” and “bodes well for a recovery in deep and ultradeep water,” Norheim said.

Still, bottlenecks will affect the deepwater and subsea sector with the number of senior professionals who have retired or left the industry since the downturn began.

“There might be a knowledge constraint,” Wilczynksi said. “This is a sector where the expertise of the engineering world and the geology work cannot be replaced on a dime.”

Norheim believes “it will be tough to get seasoned and experienced workers to go back to oil and gas.”

But those who do work the deepwater and subsea sector will begin to see a different seascape. Deepwater projects have largely been concentrated in an area the industry calls the “golden triangle,” which extends from the Gulf of Mexico and Brazil to West Africa’s Gulf of Guinea. But large new projects are emerging in Guyana, Egypt, Israel, Cyprus, Mozambique, and Tanzania to widen the deepwater domain.

Deepwater Long-Term Positive

The potential for excess supply could put a damper on strong deepwater expansion in the near future. “But in the longer term,” Robertson says, “there’s going to be supply-driven upward pressure on the oil price because we haven’t invested the money in the industry.”

“I believe the offshore rebound is probably going to be the story in the 2020s,” Wilczynski said. “It will not be a flash in the pan. It’s not going to be speculative because I believe OPEC probably has lost the ability to drive prices. We will have entered more of a market kind of pricing system.

“Sometimes, I talk to people in the US sector with a lot of exposure to the offshore,” he continued. “I tell them you might have the golden decade in the 2020s. Not all of them believe me. But I say if you look at the fundamentals, the 2020 decade will be better than the second half of the 2010 decade.”