One of Oklahoma’s top government officials announced recently that it could be many more months before the full scope of the state’s regulatory response plan for induced seismicity is proven effective.

Oklahoma is a top-five oil and gas producing state in the US that has also seen a nearly 4,000% spike in earthquakes since 2009, making it among the most seismically active regions in the country. Scientists and industry experts have concluded that the earthquakes are instances of induced seismicity brought about by the injection of produced wastewater into a fault-connected layer of rock called the Arbuckle formation.

Michael Teague, secretary of energy and environment for Oklahoma, explained that even though the state has ordered hundreds of disposal wells to cease operations or cut back their injection volumes, the earthquakes are slowing down but growing in strength. He suggested that it will take quite a bit of time for the built-up pressures inside the Arbuckle thought to be triggering the quakes to dissipate.

“The unfortunate answer to the long-term question is, this could take 2 years,” until Oklahoma’s seismic activity returns to normal, Teague said. “And there’s not much more that we could do that would make it go much faster.”

The Secretary’s remark was made during a November SPE meeting in Houston hosted by the Gulf Coast Section’s study group on wastewater management. His keynote presentation touched on several issues that his office, which collaborates with state and federal regulators, has faced in figuring out how to create a framework that promotes the production of oil and gas and also addresses the need to prevent the injection of produced water from triggering earthquakes.

Shifting Conversation

Among the earliest challenges Teague related centered on how the seismicity problem was initially being communicated and described to the general public. He expressed disappointment in the misguided attempts by activists to blame hydraulic fracturing for the earthquakes—cases of which do exist, but are very few in numbers—but also in the industry representatives who publicly downplayed the possible linkage between disposal well activity and earthquakes.

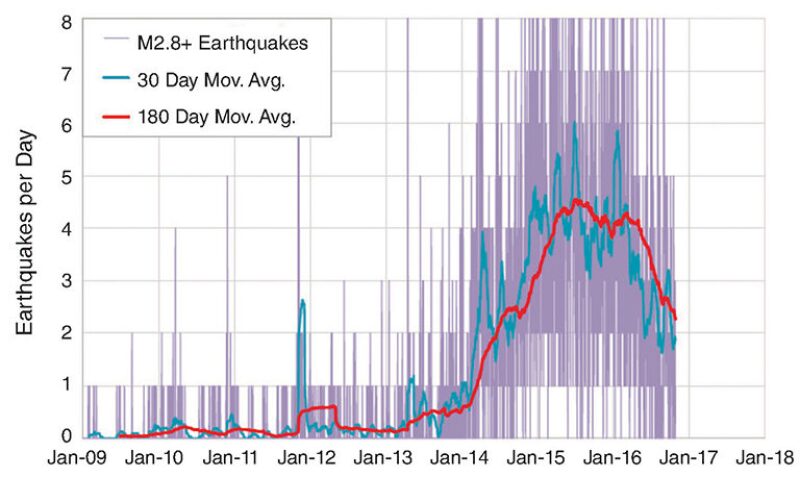

Only 2 years ago, Teague noted that some of those working in the industry speaking circuit were claiming that a scientific connection could not be established, an argument he believes was “not helpful.” Earlier in his remarks, while pointing to a chart showing the historical trend line of Oklahoma’s seismic activity, he said, “Look at how that ramps up—that is not natural.”

Times have changed. Teague said while there remain a few holdouts on the issue, the overall attitude now shared by many in the industry is praiseworthy. This position shift has resulted in the greater cooperation of oil and gas companies with regulators by way of funding for research and the state’s new disposal well reporting system, along with the donation of seismic information that has greatly expanded the state’s knowledge of its subterranean fault network.

Though there is no doubt amongst the experts on the causal relationship between disposal wells and the earthquakes, they are still unsure of the exact mechanics involved. There are conflicting theories that suggest the problem is driven by area-specific geology vs. the idea that the quakes are more related to select disposal sites with above-average injection rates.

Teague said this uncertainty underscores the need for continued research and collaboration between regulators, industry, and the universities carrying out much of this seismic investigation work. “The research isn’t done,” he said, while acknowledging, “That gets really frustrating if it’s your baby that’s getting woken up six or seven times a night, but that is the truth of the matter.”

Regulatory Evolution

Though seismicity throughout Oklahoma began rising above historic baseline levels in 2009, it would not be until 4 years later that the problem grew so bad that it prompted state officials to shut in the first disposal well linked to an earthquake.

Since then, dozens more disposal wells have been ordered to shut in and about 700 others have been plugged-up to higher injection intervals or seen their allowable injection volumes reduced by a substantial figure. The affected population of disposal wells roughly represents a quarter of the state’s total number.

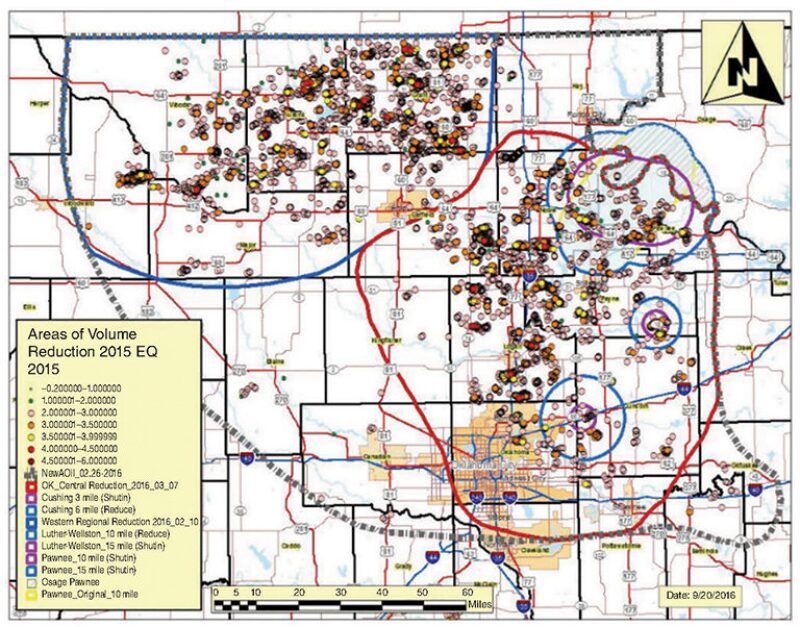

A map of the state’s “areas of volume reduction” show that three of the most regulated areas fall within the borders of a larger centrally positioned restriction zone that was established earlier. After a number of recent 4.0-magnitude or greater earthquakes occurred near the towns of Luther, Pawnee, and Cushing, the state created even tighter zones around those quakes’ epicenters.

Disposal wells located in the bullseyes of these zones, which have a radius ranging from 3 to 10 miles, have been shut in. Many more disposal wells located just a few miles beyond that innermost ring have been ordered to reduce injection volumes anywhere from half to a quarter of their 2014 monthly averages.

Teague said that regulators have settled on partial reductions for the majority of the affected disposal wells due to the potential risk of trigging earthquakes by reducing the subsurface pressure by too much, too quickly—a lesson that has been learned the hard way.

When disposal well operators were first faced with mandatory reductions, rather than inject lower volumes on a daily basis, some decided to cease injections completely for a few days, and then would start back up and inject at the maximum allowed rates for a another few days. Teague said “they were absolutely causing earthquakes” by fluctuating the injection activity like this, and implied that new rules were adopted to end this practice.

In January, the Oklahoma Corporation Commission (OCC), the state’s oil and gas regulator, issued a statement expressing similar concerns. The OCC said that a series of earthquakes that occurred in a matter of days near the town of Fairview, including four measuring at least a magnitude 4.0, may have been connected to the simultaneous startup of a number of oil and gas wells that had temporarily lost power during a storm.

The statement read that as those wells began producing again, a “tremendous volume” of produced water was generated and then subsequently injected into the Arbuckle at the same time. The statement concluded by asking that in the future, operators “gradually restore operations in the event of a sudden shutdown due to power failures.”

Stronger Magnitudes

While pointing out that the rate of earthquakes is falling, which may be due to a combination of injection restrictions and an overall reduction in the state’s oil and gas production, Teague highlighted that the magnitudes, or the intensity, of the earthquakes “are going the wrong way and nobody really understands why.”

He noted that only days before his appearance on 6 November, a 5.0-magnitude earthquake rattled the town of Cushing, Oklahoma, home to the world’s largest crude oil transportation and storage hub. No serious injuries or damage to the hub’s infrastructure were reported, however, a number of buildings in the town suffered damage. Including the Cushing earthquake, three of the state’s five strongest recorded earthquakes have occurred in 2016.

Due to the aftershocks associated with some of those events, Teague said the state would most likely end 2016 with more than 600 3.0-magnitude events—loosely held as the strength at which most people can feel ground movement. Even so, the final tally will fall far short of 2015’s total of 907 3.0-magnitude earthquakes, marking the state’s first decline in seismicity in 5 years.

Teague said these figures reflect that in some parts of Oklahoma the injection restrictions may be working, but in other areas under similar restrictions, the earthquakes are continuing largely unabated. This has been a particularly difficult situation for state officials to grapple with.

On one hand, the science is telling them that it can take perhaps 18 months for a volume reduction to have the desired effect. But on the other hand, their responsibility to the public dictates that corrective measures be implemented in a shorter timeframe.

This has led to a creeping expansion of the restriction zones when the initial mitigation strategies fail to immediately calm the seismic shifting. Teague explained that although more action is warranted when sizeable earthquakes strike within an area already under restriction, officials have grown wary of simply lumping on more and more restrictions, which he compared to Band-Aids, “because then you can’t figure out which Band-Aid is working.”

Nevertheless, Oklahoma’s regulators have announced that their next step in response to the ongoing earthquake activity in Cushing will be the creation of an even larger restriction zone that will affect more disposal wells.

For Further Reading

SPE 180365 Dynamic Considerations for Induced Seismicity by Robert Walker and Fred Aminzadeh, University of Southern California.

SPE 173383 On Liability Issues Concerning Induced Seismicity in Hydraulic Fracturing Treatments and at Injection Disposal Wells: What Petroleum Engineers Should Know by Keith Hall, Louisiana State University et al.

SPE 180461 The Effects of Faults on Induced Seismicity Potential During Water Disposal and Hydraulic Fracturing by Nick Umholtz and Ahmed Ouenes, FracGeo.