Hot shale plays tend to fall short of expectations after a few years, and the Permian Basin will be the next big test of the pattern.

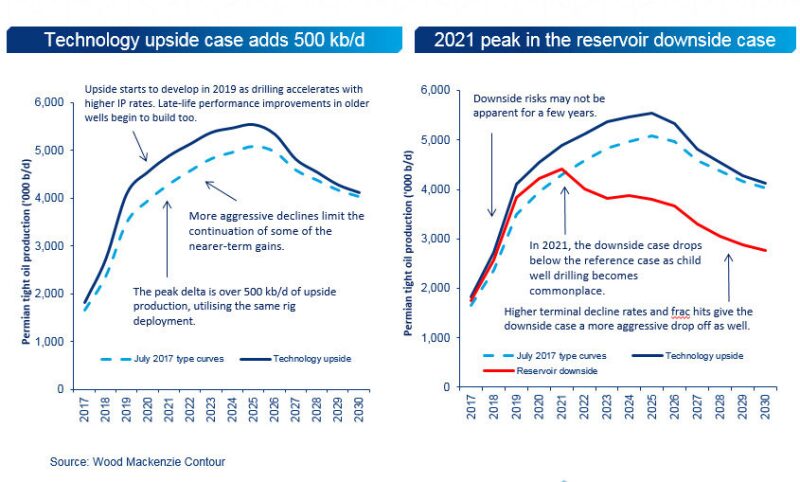

A recent technical paper by Robert Clarke, research director for Lower 48 Upstream for Wood Mackenzie, questions whether future drilling in the Permian will hit 5 million b/d in 2025 as the consultancy has predicted. Based on what he has been learning recently, some of it reported in SPE technical papers, the actual results could be worse or better, depending on how well the industry solves the problems that will come with intensive development in the Permian.

“There is a lot of exuberance in low-cost unconventional plays in their early years,” he said on a recent podcast from Wood Mackenzie, adding, “In retrospect, the first 3 years of a shale play are easy, then it gets harder.”

While older plays such as the Marcellus and Bakken hit economic limits due to limited pipeline capacity, Clarke’s big concern in the Permian is more geological. There have been reports that wells added to develop rock near the original “parent wells” may deliver significantly lower estimated ultimate recoveries (EUR).

Recent technical papers delivered at the Unconventional Resources Technology Conference reported that infill wells—“child wells”—could have ultimate recovery rates 20-40% lower than the parent wells nearby, he said.

To test if that shortfall could become common, Clarke searched the Wood Mackenzie North American well database to find parent and child pairs similarly completed. Those 20 Eagle Ford wells showed similar drop-offs in the second generation.

While the percentage of infill wells is not significant now, the child wells will have a large impact next decade.

“You are drilling wells with a EUR of X and we will be drilling really, really hard for the next 3-4 years. We will exhaust a lot of parent locations,” Clarke said. “We will keep drilling hard but we will be drilling into pressure-depleted areas and if all the EURs for those future child wells are 0.7 X (EUR), it will be very, very hard for the Permian to keep growing.”

Hard but Possible

While these observations will be factored in when Wood Mackenzie adjusts its production outlook this fall, it is not sending a clear signal that production will fall short of past targets. Clarke sees it as “an opportunity to highlight the need for continued innovation.”

“We are not saying it peaks and it is done” early next decade, but he added, “just because we are in a position of breaking even below $45/bbl does not mean we have won.”

Adding wells that produce less in developed areas can still be profitable in spots where the cost of developing the field has already been paid, said R.T. Dukes, research director for Wood Mackenzie, who discussed the outlook with Clarke on the podcast. And the productivity loss per foot will be easy to miss because wells now are so much longer.

But the productivity issues related to pressure losses could be hard to work around, even if drilling shifts to higher or lower horizons.

“There is a lot of vertical communications between all the zones. That is why some shallower zones are so prolific, so highly pressured,” Clarke said, during a call while visiting Midland to learn more from operators. Some of the bigger operators have already made adjustments, with wider well spacing or by using new patterns for drilling and completing well pads, he said.

Major Uncertainty

Clarke’s three scenarios ranged from 1 mm B/D less than Wood Mackenzie’s 5 mm B/D reference case for 2025, to more than a 500,000 B/D above it. The gap between the high and low estimates offered in the scenarios in the report is 1.5 mm b/d, which Clarke pointed out is “more than the Bakken has ever produced.”

Experience shows that the industry is capable of significant technical advances. For example, the average estimated ultimate recovery for wells in the Wolfcamp, a prime unconventional horizon in the Permian, doubled between 2013 and 2016 due to better reservoir models, targeting the best rock, and completions that were bigger and better executed.

Those solutions, though, depended on targeting the best rock, which is gassy with relatively high pressure. As that pressure drops, the gas drives production of liquids. Over time, the production and pressure goes down. In the future, a high percentage of the new wells could be 500 ft or less from these low-pressure zones.

While completions are designed to focus on evenly fracturing rock within a confined area, it is clearly hard to control the flow of the high-pressure streams injected during hydraulic fracturing. A recurring theme in the presentations are URTec was frac hits—fluid flowing from well to well during fracturing that can significantly reduce production, but not always.

Tight spacing increases the risk of hits, but the industry is not likely to stop doing it because there is an upside to fracturing nearby. To get a sense of where the industry is headed, Clarke will keep up on the technical papers.

“We follow the technical commentary from SPE and others because we think it gives us a notion of what will happen in the future,” he said, adding, “some things that occurred that were important with investors we can back up and say that was very important to geologists and engineers a year before.”