Reduced budgets, lower operating and capital expenditure, job cuts, and work furloughs have become commonplace in the midst of the pandemic. Record-low crude prices, ample supply, and weak demand have impacted nearly every segment of the industry. Among the hardest hit, though, have been capital projects.

As construction activity across the industry has slowed or stopped, companies are scrambling to secure supply chains and rebalance project portfolios due to work process disruptions and engineering delays.

A few market intelligence agencies have provided their insights on ways the pandemic would impact the industry, while one industry group outlined how companies should prepare to restart key projects.

What Do the Experts Say?

In March, before WTI crude prices hit negative territory, research group Rystad Energy said a combination of weaker oil and gas demand and lower oil prices could lead exploration and production (E&P) companies to reduce project sanctioning by $131 billion, or 68% year-on-year. Its pre-coronavirus forecast had total onshore and offshore projects representing about $190 billion of investments that would be sanctioned this year, which was below the 2019 estimate of $192 billion.

Rystad also said forecast growth in newly commissioned solar and wind projects would be wiped out for 2020 and cut by a further 10% next year as the US dollar surges and international currencies fall.

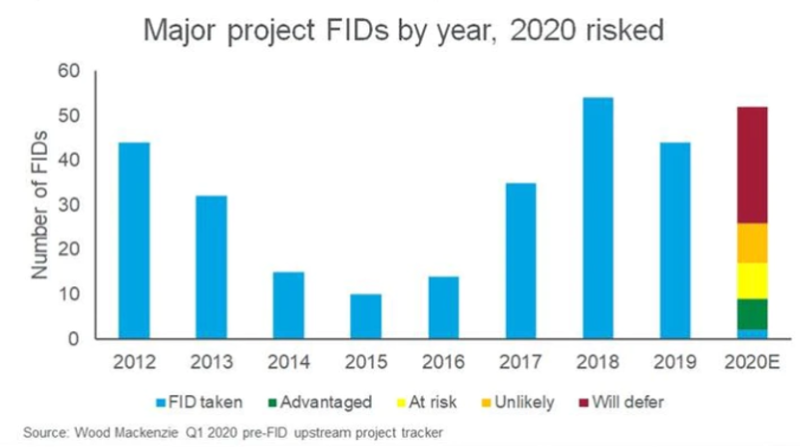

In early April, energy intelligence group Wood Mackenzie, which tracks all project final investment decisions (FIDs) globally, said it expects 2020 to have a similar drop in FIDs compared to 2014–2016, as many oil majors have announced reviews and deferrals of high-profile projects.

Wood Mackenzie added that most projects look robust at $50/bbl, but almost none of them work at $30/bbl for break-even cost—so only the most strategic and the most core projects are likely to get the go-ahead.

In mid-April, analytics group RBN Energy said for many of the already-struggling second wave of US liquefaction projects still under development, the one-two punch of the crude oil price crash and COVID-related lockdowns had further stymied—or in some cases even reversed—their progress toward securing long-term capacity commitments and reaching FIDs anytime soon.

This month, RBN Energy added while many companies have ratcheted back their 2020 capital spending plans, the bulk of their major crude oil, natural gas projects already under construction are proceeding. Most project delays should last only a few months, and a handful are either being reworked or deferred indefinitely.

As countries start easing quarantine restrictions and stay-at-home orders, many oil and gas companies will begin returning to normal operations. Of interest will be the way companies respond to such challenges and how projects will be positioned for restart.

The Independent Project Analysis (IPA) Director of Oil and Gas Practice, Neeraj Nandurdikar, said from an operations standpoint, no one region stands out above the rest when it comes to project delays.

“Because many companies are global players, it’s more about the total portfolio of projects,” said Nandurdikar. “How much oil, gas, deepwater, and onshore—that combination determines the mix and optionality that companies want to have.”

However, because Asia is a larger continent, it is being impacted more broadly in terms of construction suppliers, he added.

In a recent article, IPA said most large projects in the industry take about 7–9 years from discovery to first oil/gas; one implication is that any project authorized in 2020 will not start up until 2024 or later.

So, if a project is competitive, IPA said it would be a good time to continue with the project or at least to position the project to be ready at the starting line.

“In doing so, as soon as the rebound occurs and pandemic‑related constraints are lifted, these projects can move quickly and smoothly into execution,” Nandurdikar said. “There are projects that are moving along, especially large deepwater. Suddenly large-scale developments that take 7–8 years are moving along. Smaller-scale tiebacks are moving along, especially if they were already in motion. “

Getting back to project development may be quicker than expected, though, as oil prices started to recover in mid-May alongside a 2-month high in Nymex WTI crude futures.

Industry Recovering Quicker Than Expected?

Since Nymex WTI hit its record low price of -$37.63/bbl on 20 April, the market has been gradually recovering. One month later, on 20 May, the Nymex WTI settled at a 10-week high of $33.49/bbl.

After US domestic crude inventory increased for 15 consecutive weeks, peaking at 532.2 million bbl for the week ending 1 May, demand finally started kicking in. The latest EIA data for the week ending 15 May showed domestic crude oil inventory at 526.5 million bbl, representing a second consecutive weekly decline.

As recovery begins, actions taken by the oil and gas industry may be similar to actions taken after previous downturns.

Key Factors and Lessons Learned To Restart Projects

The IPA said that in the short run, canceling a project may appear a rational move to manage cash flow—as projects are easier to cancel than dividends.

However, more sophisticated companies, with stronger balance sheets, may recognize the long-term nature of certain opportunities and continue moving those projects along.

Nandurdikar pointed out that when oil prices crashed in the 2008–2009 timeframe, driven by the global financial crisis, projects were bloated, meaning the industry routinely oversized, overscoped, and overcapitalized its projects. During that timeframe, it was the right thing to do to challenge projects to become more competitive, lean, and fit, and to right‑size the scope.

As the graphic shows, however, there was little improvement in reducing project costs.

Source: IPA

“We squandered our first chance,” Nandurdikar said.

Six years later, in 2014, and facing another price drop, the industry was right back where it was in 2008–2009. During that time, the industry realized it was entering a lower forever period, as IPA points out. Some firms saw this as the right time to pivot the way projects should be done in the face of growing competition from shale, liquefied natural gas (LNG), and renewables.

Another common area for cost savings, IPA pointed out, is in the supply chain.

Like projects, the supply chain in the 2008–2009 timeframe had a lot of room to give. Supply chain prices increased because of the demand in project activity. Nandurdikar said suppliers had to provide discounts and renegotiate contracts, and in some cases, according to IPA data, supply chain costs decreased by 15–25%—more in subsea and floating production storage and offloading markets and, to a lesser extent, in other areas.

A third issue was people.

Economic downturns of the past have caused companies to reduce their workforce, resulting in the loss of key people. As activity picks up, there is usually a rush on projects and project services, but Nandurdikar emphasized it is a mistake to assume that just because an engineering or oilfield services firm is around when restarting, the service people with detailed knowledge of the project will also remain..

Decisions to downsize project capability in the past have created a long-term capability challenge, leaving companies with a difficult time finding and/or developing the skills they need, especially in core project capabilities.

The weakness of competencies, skills, and capabilities is evident in the error rates in engineering drawings, quality issues in construction, and basic mistakes in quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC). IPA said it is aware of several projects experiencing severe startup and ramp up delays due to construction and engineering quality issues exacerbated by poor-quality QA/QC.

Consequences of Not Being Prepared

One consequence of not being prepared—on a project‑by‑project basis—is that when a rebound does occur, companies rush to get projects in queue with suppliers, vendors, and yards, creating heavy demand on capacity that will lead to price spikes.

“Getting back in position to restart depends on where you are in the project phase,” said Nandurdikar. “The most difficult element is the uncertainty on when and how to get back up.”

When asked how operators may be shifting their views toward business objectives moving forward, Nandurdikar said he hopes collaboration might become the way for the entire industry to succeed.

“This pandemic is really the test,” he said. “Are companies going to just put out announcements, or are they actually going to work together to stay alive?”

This period might even be the right time to work with the supply chain to find symbolic ways to keep the supply chain healthy, productive, and resilient, according to IPA. The group said this will prevent current stresses from morphing into catastrophic issues.