This article marks the beginning of a Q&A series contributed to JPT by the SPE Research and Development Technical Section (RDTS). The series will highlight innovative ideas and analysis shaping the future of energy, with a focus on emerging technologies and their roadmaps, potential, and impact. With these conversations, we hope to inspire dialogue and accelerate progress across new energy frontiers.

In this article, Gaurav Agrawal and Michael Traver of RDTS spoke with Amy Bason of the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI) about the status of decarbonization in critical global transportation and the solutions being worked on.

Amy Bason is deputy vice president of strategy and policy at the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI). She works with the transportation and energy efficiency work streams and the reporting taskforce, managing their agendas and day-to-day activities while ensuring close collaboration with other work streams at OGCI. Bason has 2 decades of experience in energy policy, having previously worked with Climate Investment and in Saudi Aramco’s Washington, DC, office. She holds an MA in applied economics and a BA in Middle East studies.

RDTS: How do you segment the transportation sector and where does it stand in carbon footprint?

Bason: What we call “transportation” comprises four distinct and significant subsectors: light-duty passenger vehicles, heavy-duty commercial vehicles, maritime shipping, and aviation. Together, these four sectors produce around 24% of the global total energy-related greenhouse gas emissions, or 40 Gt CO2e.

RDTS: Since these are quite different segments, how do we roadmap carbon reduction in each segment?

Bason: Despite the differences, they all primarily follow the same basic principles of fuel combustion to generate motive power. As a result, regional and global regulations and policies seek to improve energy efficiency and shift away from traditional petroleum-based hydrocarbon fuels as the primary means of reducing carbon emissions.

RDTS: How are the engine-efficiency improvements impacting carbon-footprint reduction?

Bason: In the commercial sector where the cost of fuel is a major operational expense, engine efficiency and system-level engineering are top priorities. For example, modern tanker vessels may be built with highly efficient two-stroke diesel engines with waste-heat-recovery devices in the exhaust to maximize overall fuel efficiency and minimize operating costs while delivering a lower carbon footprint. Meanwhile, in the passenger car segment, where many buyers may prioritize characteristics other than fuel efficiency, you see more reliance on regulations like Corporate Average Fuel Economy, or CAFE, to address carbon emissions.

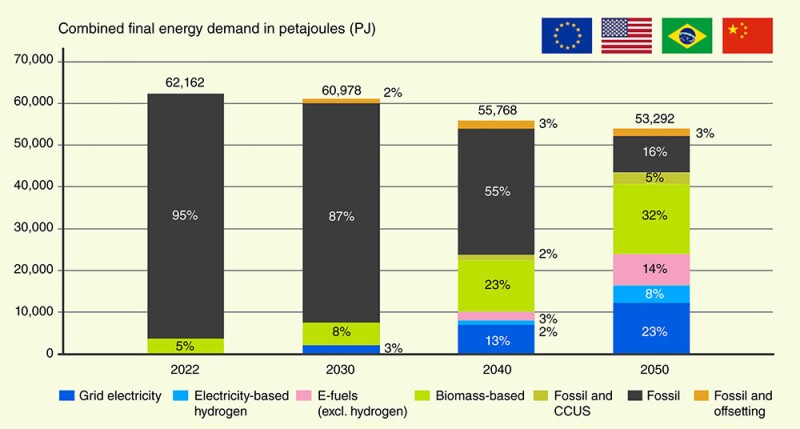

RDTS: How are various fuel mixes likely to change by 2050?

Bason: Given the rapidly approaching deadlines, traditional fuels will almost certainly still be part of the energy mix in the transportation sector in 2050. Electrification is happening, but some vehicles and vessels are very difficult to electrify. There has been a lot of progress with electrification in the light-duty vehicle sector.

However, international air travel, for instance, will still be reliant on hydrocarbon fuels because their energy density is incredibly hard to beat. Nevertheless, international bodies like the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) have declared an ambition to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

The only feasible route to achieve this is through the large-scale adoption of low-carbon fuels, primarily from biomass and synthetic routes. However, these fuels still need to meet the quality and performance specifications as set by standards organizations, so they’ll look and act much like today’s fuels but with a significantly lower carbon footprint.

Other segments like heavy-duty on-road trucks and marine vessels may explore a variety of fuels to achieve similar net-zero ambitions with hydrogen, methanol, and ammonia, all being seriously considered in addition to drop-in, bio‑based, and synthetic fuels.

RDTS: What is e-fuel?

Bason: E-fuels or electro-fuels typically refer to fuels that are derived by combining hydrogen sourced from renewable electricity with carbon dioxide to produce a synthetic hydrocarbon fuel similar in chemistry to those derived from subsurface petroleum. Synthetically produced gasoline and diesel most commonly come to mind when using the term e-fuel, but it can also be applied to ammonia, methanol, methane, and other current or potential fuels.

RDTS: How is the carbon footprint of e-fuel and biomass-derived fuel different from the traditional fossil fuel?

Bason: Fundamentally, petroleum and biomass-derived fuels (and e-fuels to an extent) are created using the same basic chemistry principles, but it’s the timescale that differentiates them. The origins of petroleum are in organic material from planktonic plants and animals in ancient marine environments, similar in form to biomass used in the biofuel industry.

However, burning petroleum-derived products releases formerly sequestered CO2, while biomass first removes CO2 from the air as plants grow before releasing it during combustion. That makes all the difference in whether a fuel’s combusted emissions are increasing the net concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere.

Similarly, very-low-carbon e-fuels can source their carbon from direct air capture systems that pull CO2 out of the air, leading to little, if any, net increase in CO2 levels.

Importantly, these low-carbon fuels can be blended with traditional petroleum fuels to lower the carbon footprint in the short term while accommodating long-term production scaling.

RDTS: What is the readiness of e-fuel and biomass fuel? What are the respective technology or supply chain elements that would expand their adoption?

Bason: Biomass is already widely used as there is a robust market for ethanol, renewable diesel, and sustainable aviation fuel derived from various biofeedstocks. However, to achieve net-zero ambitions, next-generation processes must be deployed at scale to access the vast quantities of agricultural and forestry residues that are projected to be available. Some of the products of these processes can potentially be used in refineries, offering a pathway to provide lower-carbon fuels while utilizing existing infrastructure and capital investments.

Meanwhile, e-fuel processes have been under development for over a century, and much of the chemistry is well understood. The primary hurdles in this value chain include competition for renewable electricity and the high cost of the product. To deliver low-carbon-intensity e-fuels, CO2 must come from either biogenic sources or through direct air capture, and these suffer from supply and cost constraints.

RDTS: What is sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), and how widely is it used today?

Bason: ICAO defines SAF as “renewable or waste-derived aviation fuels that meet sustainability criteria” as set out in the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA). Practically speaking, they are fuels that meet both the sustainability criteria in CORSIA and comply with the approved conversion processes outlined in ASTM Standards D7566 and D1655.

SAF is already in use by several national and international airlines, but total volumes still amount to about 0.5% of total aviation fuel demand. At present, SAF can be blended with petroleum fuels up to a 50% limit due to some material incompatibilities with existing engines, but work is ongoing to allow the use of 100% SAF.

RDTS: What international standards govern SAF, e-fuel, and biomass fuels?

Bason: Each transportation sector independently manages its fuel specifications and standards to comply with both greenhouse gas reduction targets and pollutant regulations while delivering expected performance. The on-road diesel market, for instance, relies on ASTM D975 for commercial diesel fuel with up to 5% biodiesel while ASTM D7467 and ASTM D6751 apply for higher blends. Renewable diesel, owing to its chemical similarity to petroleum diesel, is governed by D975. Similar standards from European Committee for Standardization (CEN), International Organization for Standardization (ISO), and ASTM International are applicable for fuels intended for other transportation markets.

RDTS: Are there any safety risks (e.g., in use, handling, transport) that are being addressed with these new energy carriers?

Bason: For blendable fuels similar to existing petroleum fuels, the safety requirements are largely the same, as they are handled with existing infrastructure and refueling systems. It is the non-drop-in fuels such as hydrogen, methanol, and ammonia that require new safety protocols. Since the chemical industry has a long history of safely handling these fuels, the safety requirements are fairly well understood and the challenge is translating those requirements into new environments such as fuel bunkering, onboard storage, and fuel delivery systems.

There is a significant amount of ongoing work to address these challenges and ensure a safe working environment for the drivers and crews that will operate these vehicles and vessels.

RDTS: How feasible is onboard carbon capture on ships?

Bason: Technically, outfitting a vessel with a carbon capture system is entirely feasible, and several suppliers offer complete systems to do just that. The efficacy of the system depends on multiple variables, governed by the vessel, its route, and the fuel being used, but the greatest impact comes from the amount of waste heat available to drive the CO2 release process. Insufficient waste heat means that extra fuel may need to be burned to provide the necessary energy, and this has a direct impact on the operating cost.

The greater barrier to the market is the lack of infrastructure to offload and manage the captured CO2, but this may be an area where the oil and gas industry could establish leadership as the carbon capture industry begins to develop and CO2 becomes a commodity.

RDTS: How do we benefit from hydrogen?

Bason: As we evaluate fuel mix options for a net-zero transportation system, it is clear that hydrogen has to play a strong role.

The first opportunities will likely emerge in decarbonizing the oil and gas industry’s own operations, but other industries like steel and power generation are also eyeing low-carbon-intensity hydrogen as a major lever.

As demand rises, opportunities will emerge to provide hydrogen as a direct-use fuel and as a precursor molecule to ammonia, methanol, and synthetic fuels.

Hydrogen and hydrogen carriers also offer the means of storing and transporting energy. So, opportunities will likely emerge in global management and trade, whether that’s converting surplus renewable electricity at local wind and solar installations or delivering renewable electricity across oceans from areas of low generation cost to demand markets.

RDTS: What is the role of technology in expanding the use of hydrogen-based carriers?

Bason: A major barrier to the expansion of hydrogen and hydrogen-derived fuels currently revolves around cost and scale. The most likely role of technology is in finding new, innovative ways to produce and deliver hydrogen at lower cost points and greater volumes.

RDTS: What are the technologies or trends that you will be watching for?

Bason: Two areas I’m watching closely are hydrogen-fueled internal combustion engines (ICEs) and biomass conversion processes.

Hydrogen ICEs offer a much more cost-effective means of decarbonizing the heavy-duty truck sector and come very close to meeting the zero-emissions requirements of regulatory agencies. Allowing them to be used for regulatory compliance could have a substantial impact on hydrogen demand in the short and mid‑term.

Similarly, progress with biomass conversion processes could unlock vast quantities of biofeedstocks that could change the way fuels are perceived.

RDTS: What advice do you have for young R&D professionals?

Bason: If you’re attracted to the R&D space, I suggest getting direct experience with problems your company’s engineers and scientists face and familiarizing yourself with the tools and processes they use daily.

Half of the challenge inside R&D departments is in effectively capturing the true problem to be solved and ensuring that the solution can be practically implemented.

There’s a lot of wisdom in the proverb “necessity is the mother of invention.”

Michael Traver, PhD, SPE, recently retired from Saudi Aramco. While at Aramco he worked as a senior researcher in the transport technologies division in Detroit, Michigan. He also chaired the transportation work stream at the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative, a voluntary, CEO-led oil and gas industry initiative to catalyze actions on climate change through collaboration and engagement.

Gaurav Agrawal, PhD, SPE, is the vice chair of the SPE R&D Technical Section, He has organized events in energy transition, artificial intelligence, digital technologies, and other areas. Previously he was a senior vice president of R&D at Newpark Resources in Houston and vice president of the Saudi Arabia Dhahran Technology Center at Baker Hughes. He has over 85 granted US patents.