“Down but not out” is how Westwood Global Energy Group described exploration drilling in an article based on its State of Exploration 2020 Report. The Baker Hughes rig count provides supporting details. On 12 May, the data showed 339 active rigs in the United States—the lowest level since the rig count was introduced in 1987. On 1 June, the US count plunged to 301 in its 12th week of losses. At the worst of the 2014–2016 oil bust—the previous lowest point on record—404 rigs were operating.

The worldwide rig count for May was 1,176, down 338 from the 1,514 counted in April and down 1,006 from the 2,182 counted in May 2019. And, Rystad predicted on 28 May that more than half of the world’s planned licensing rounds for 2020 are likely to be canceled.

The consensus among industry experts is that exploration will be hit by some of the deepest cuts inflicted by the coronavirus pandemic, the biggest oil market crash in history, and the transition to a low-carbon energy future. The silver lining is that there is still a business case for exploration despite these difficult times. Julie Wilson, director of global exploration research for Wood Mackenzie, said in a recent virtual panel discussion that the role of exploration in replacing supply sources in current portfolios with “new and better” barrels of oil equivalent (BOE) will continue over the next 20 years. But for explorers to prosper, those barrels will need to be low in cost and emissions.

Rude Awakening

For the exploration sector, 2020 began with a degree of cautious optimism and increasing activity. Confidence had returned with improved performance, the highest commercial success rate (CSR) in 10 years, and the discovery in 2019 of several multi-billion-barrel plays. Explorers were keenly aware of challenges ahead, including investability, capital efficiency, the risks of exploring in deep water, and societal pressure to move toward energy transition. But, the overall outlook was for another 30 years of profitable exploration.

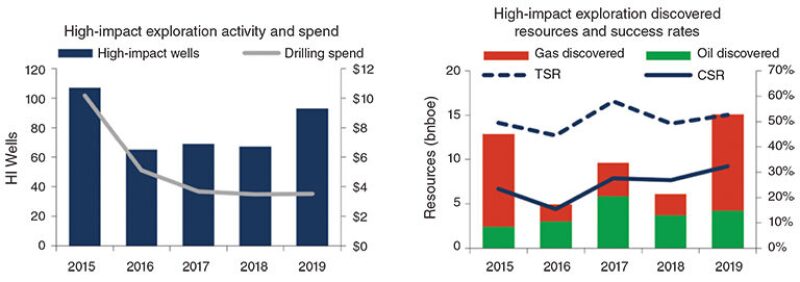

At the start of the year, the high-impact well count had been expected to be similar or slightly higher than the 93 wells completed in 2019. Westwood now expects around 60 to 70 high-impact exploration wells to be completed by the end of 2020, a decline of up to 35% and back to the numbers and volumes seen from 2016 to 2018 following the 2014 oil price crash. In the Gulf of Mexico (GOM), the number of executed high-impact wells has declined from 34 to 15, all in deep water. Seven of those have been spudded. For independent GOM explorers, the number of expected wells went from 13 to one, as companies decided to focus their bare-minimum budgets on near-term production.

Around 2.1 billion BOE have been discovered so far this year from the 26 high-impact wells completed, 2.5 billion BOE of risked volume is being tested by wells currently drilling, and another 4.3 billion BOE risked from the remaining “expected” wells yet to spud. Westwood now expects a total volume of approximately 6 to 9 billion BOE to be discovered in 2020, down 40% or more from 2019’s 15 billion BOE (Fig. 1).

All regions are expected to see a decline in drilling, said Westwood, with North America (including Mexico) likely to take the hardest hit, although it will still see the most wells. The eastern Mediterranean may have very few high-impact wells the rest of the year, and Sub-Saharan Africa will likely have only three to five.

“The coronavirus pandemic has done in a handful of months what even a 27-year civil war did not—brought oil drilling to a halt in Angola,” said Reuters on 26 May. Sarah McLean, senior analyst at IHS Markit, said this was the first time since the firm began keeping records in 1984 that Africa’s second-largest oil producer had not had a single rig drilling. The London-based information provider had expected at least 10 rigs to be operating there by the end of 2020, the highest number for any African nation this year.

Drilling plans in the central North Sea, Guyana, Suriname, and in the shallow-water Campeche area in Mexico are likely to be less affected, although COVID-19 may limit operations even where companies want to drill.

According to Rystad, at least nine of the world’s top planned exploration wells for 2020 are at risk of being suspended as a result of the combined effects of the COVID-19 virus and the oil price war. These wells, located in Norway, Brazil, the Bahamas, Guyana, the US, Gambia, and Namibia, would target a combined 7 billion BOE. The wells are at risk, said Rystad, because of their lack of commercial viability under the current price levels, shutdowns that affect the supplies of equipment components, operators’ prioritization among other targets, and limitations in crew movements, among other reasons.

A Strategic Move to Stratigraphic Traps

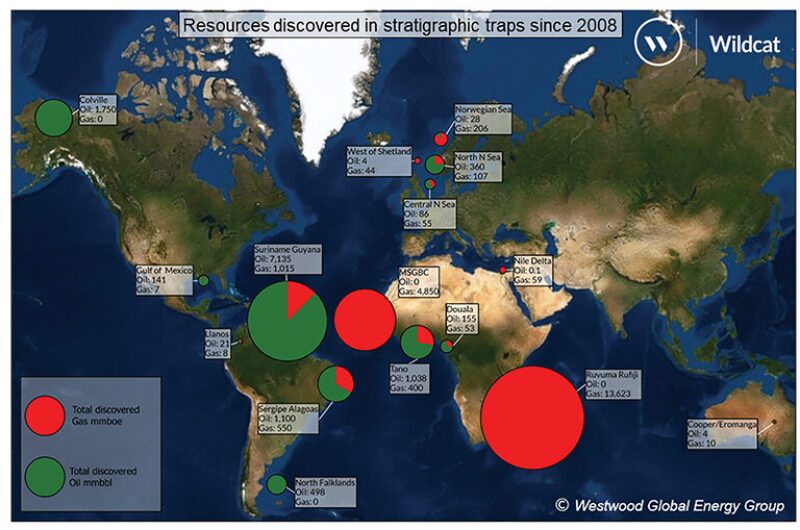

One noteworthy trend in exploration strategy that is likely to continue is the increasing importance of stratigraphic traps. Westwood noted in its 2020 report that, during the past decade, more oil and gas were discovered in stratigraphic traps than in any other trap type (Fig. 2).

A total of 35 billion BOE has been discovered in clastic stratigraphic traps since 2008, of which 22 billion BOE (132 Tcf) were gas and 13 billion bbl were oil. The firm reports further that 75% of the oil resources and 95% of the gas were discovered in deep water.

The exploration has been concentrated geographically along the Atlantic margin, where 43% of the wells were drilled in 29 basins. The most prolific basins were Suriname-Guyana, Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea/Bissau and Guinea/Conakry (MSGBC), Rovuma-Rufiji, and Colville, all of which yielded major new plays. Another 20% of wells have been drilled in the North Sea. Only 18 basins globally saw more than five stratigraphic traps tested.

Stratigraphic traps have shown a larger average discovery size and a lower drilling finding cost than other traps. With no structural component, these traps have often been considered higher risk than structural traps. But this is no longer the case, particularly as the industry has become better at leveraging seismic attributes and integrating with geological models in exploring for these traps. Their CSR improved from 21% between 2014 and 2016 to 50% from 2017 to 2019.

Marine turbidite sandstones in stratigraphic traps in passive margin settings delivered 90% of discovered commercial resources; finding stacked or extensive traps was key to commercial success. Large commercial deepwater standalone discoveries in clastic reservoirs are now most likely to be found in stratigraphic traps and traps with stratigraphic components. Looking beyond deepwater passive margins may deliver the next wave of traps, said Westwood.

A Changing Competitive Landscape

In addition to the increasing focus on stratigraphic traps, the competitive landscape for exploration is changing in other ways. Access to capital is increasingly difficult for companies that are not self-funding, especially smaller companies that have traditionally played the roles of pathfinder and innovator. Conversely, majors are allocating what they can of their reduced budgets to maintain high-impact exploration and its potential positive impact on future supply options. And those with the means to invest at the bottom of the cost cycle and pursue rapid development may be in a superior position to benefit from lower competition, governments desperate to sustain exploration, and recovering prices.

NOC shifts. In the short term, the recent trend toward national oil company (NOC) expansion internationally is reversing, as NOCs prioritize domestic activity. Supermajors and NOCs participated in 80% of the high-impact wells drilled in 2019. Wood Mackenzie reported in May that NOCs globally are estimated to cut exploration budgets by over a quarter on average in 2020, to about $14 billion collectively.

“Most NOCs consistently spent be-tween 12 and 35% of their upstream budgets on exploration, an average of about 17% over the 2015 to 2019 period. This is significantly higher than the majors’ average spend of 8% of upstream budgets on exploration,” said Wood Mackenzie Senior Analyst Huong Tra Ho. Nonetheless, he explained, strong mandates that prioritize domestic activity and contribution to government budgets will mean deeper cuts to overseas budgets.

Two factors—constrained domestic resources and financial strength—create contrasts. As organically added resources are expected to contribute between 50 and 70% of their production in the next decade, Petronas and CNOOC are striving to protect their exploration plans as much as possible. By contrast, Gazprom and Rosneft have long reserve lives and feel less pressure to rush their exploration plans. Similarly, Petronas, PTTEP, CNOOC, and others with strong balance sheets are better able to continue with most of their high-impact exploration ambitions.

“Exploration budget cuts, while necessary today, will impact companies’ future growth and sustainability. Given how important exploration is for the NOCs and their growing share of global new discoveries, these budget cuts are likely short-term measures rather than long-term,” said Ho. “We expect NOCs to revitalize their exploration programs as the sector recovers.”

Frontier dilemma. Accessing plays at the early stage of the exploration curve has never been more important, and to do so, explorers need to be in at the start. Eleven of the top 16 discoveries in 2019 were made at the emerging stage, and 90% of discovered resources in plays opened since 2010 have been captured by companies that already held acreage in the new plays as they were opened.

A fast-follower strategy generally has not worked for emerging plays. Fast-follower companies were only able to access 10% of the discovered resource in plays opened since 2010.

Yet, many companies can’t afford the challenges that face frontier explorers. For example, frontier drilling commercial success rates were only 7% in the last five years. Additionally, the need to consider full-cycle time frames and above-ground challenges is important now more than ever. Over the last decade, the median time from frontier discovery to first production has been 8.5 years.

This dilemma has forced explorers to make a decision: a.) Continue to innovate and tolerate frontier play risk (if they can afford it) to sustain the emerging play prospect inventory; or b.) abandon new frontier exploration, either temporarily or permanently. Kosmos Energy, known as a successful specialist frontier explorer, has transitioned to a full-cycle E&P company and has announced it will not be accessing any new-frontier long-cycle acreage in light of the energy transition. Woodside also announced that it will no longer invest in long-cycle exploration.

E&Ps justified US light, tight oil on the basis that it was short cycle and flexible. The problem is that it is also expensive. Deepwater frontier oil can be low cost and shorter cycle. Jubilee and Liza were 3.5 and 4.5 years, respectively, from discovery to first oil.

Infrastructure-led, near-field offshore drilling has become an obvious choice for many, with an average cycle of 3 years from discovery to first production. There are limits to the number of drillable prospects in tieback distance, and high-impact discoveries in mature basins are rare. However, near-asset subsea tiebacks accounted for much of the 2019 growth in exploration wells. A degree of stability and certainty could provide a boost to these swing-type, high-return exploration wells and to the sustainability and competitive positions of the independents who excel at them and drove the 2019 success.

ESG impact. The environment/social/governance (ESG) investment movement and transition to low-carbon energy mean that oil is losing favor, natural gas is becoming more popular, and discoveries with low breakeven costs and low emissions will have premium value in the future. Companies will assess emissions before investing.

What’s Next?

Without question, this is a difficult time for exploration, but there is still a business case for it, say the experts. The discovered-resource opportunity for oil and gas grows. An estimated 51% of the high-impact resources discovered since 2008 remain undeveloped, and 34 billion BOE of potentially commercial resources discovered between 2008 and 2016 have shown no sign of progression since 2016. This offers significant opportunity and competition for exploration if the barriers to commercialization can be removed.

Explorers have raised their game and need to continue to do so, with a focus on finding low-cost, low-emissions reserves. Those who do can continue to prosper in the transition to come. In the immediate term, however, the industry may have to do something totally counterintuitive: Let exploration take a back seat.