The Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), localized in the north and northeast of Iraq, is an autonomous territory recognized in the Iraqi constitution of 2005. Its capital and most populated city, Erbil, is also one of oldest inhabited cities in the world, dated back to around 6000 BC. The KRI’s Parliament was established in Erbil in 1970.

In a highly mountainous setting, the KRI hosts colorful biodiversity and a wide range of climate and fertile lands suitable for varied agriculture. Geologically, the Zagros fold and thrust belt, to the north and northeast of the Region, is the most relevant feature. Originating from the collision between the Arabic and Eurasian plates, it gives the subsurface unique structural complexity.

The first exploration well in the KRI dates back to 1901, drilled in Chia Surkh in the south of the territory. The well encountered oil shows but was abandoned. Later in 1927, the discovery of Baba Gurgur near Kirkuk was what really ignited the production of oil in northern Iraq. This field, controlled by the Federal Government of Iraq and operated by the Iraq Petroleum Company at that time, was brought onto production in 1934. Over 25 years later, in 1960, the first well was drilled at the Taq Taq field, and the discovery of oil was declared in 1978 following the drilling of a second exploration well. Nonetheless, this field was not appraised until the 1990s.

In 2003, the end of the Iraq War triggered the interest of international oil companies (IOCs), which started to arrive in the KRI. In 2005, DNO spudded Tawke-1 in its Tawke license, marking the commencement of the current era in the KRI’s oil industry. The Tawke field started production in 2007, while the previously appraised Taq Taq field started producing in 2008. The Khurmala Dome field, part of the Kirkuk’s complex, was taken over by KAR in 2004 with a remit to revive production and increase it to the 100,000 BOPD mark. As a result, Tawke, Taq Taq, and Khurmala Dome became the three dominant fields in the KRI’s oil production at that time. When it comes to gas, the Khor Mor field started production in newly built facilities in 2008.

This initial period of exploration, appraisal, and development in the KRI, up to 2014, has been extensively covered in a work published by David Mackertich and Adnan Samarrai in April 2015. During this time, more than 20 IOCs entered the region, and about 200 wells were drilled. By the end of 2013 the average daily production was 215,000 BOPD, mostly from the three main fields previously mentioned.

Over the past decade, production has increased, coming from a larger number of fields compared to the period before 2014. While some operators started or increased oil production in their fields, other fields reached a peak and started to decline. The first expansion of the Khor Mor gas plant in 2018 allowed for more gas production, and some operators started evaluating and implementing gas capture and utilization projects. Moreover, the more intense drilling and production activity enabled a deeper understanding of the region’s fractured carbonate reservoirs and a learning process on how to develop them more effectively.

Regional and global events have resulted in cycles of production and fluctuations in activity level. Key among those events were the Kurdistan Regional Government’s (KRG) takeover and successive loss of control of the fields in the Kirkuk disputed area, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, and the closure of the Iraq-Turkey export pipeline (ITP) in 2023. At the time of writing, the latter has not yet reopened.

This article uses available production data to analyze the performance of key fields and comments on the different factors that have impacted either individual fields or the overall production and activity in the region. By collecting, integrating, and correlating data from diverse sources, the authors aim to provide a solid overview on the main challenges and production achievements of the oil and gas industry in the KRI during the period from 2014 to 2023, enabling a broader comprehension of its evolution, current situation, and future opportunities.

KRI, 2014–2023: A Decade of Oil Activity Consolidation and Growth Concluding With the ITP Closure

In March 2023, Turkey halted the transportation and loading of both Kurdish and Iraqi oil into the ITP, thus stopping the flow of more than 430,000 BOPD from the KRI to be exported to international markets. This decision came after a ruling by the International Chamber of Commerce on an arbitration that had been started by the Federal Government of Iraq in 2014. This closing of the pipeline marked a break in a decade characterized by intensive field development which led to production from a larger number of fields, as well as the decline of some of the earliest big producers.

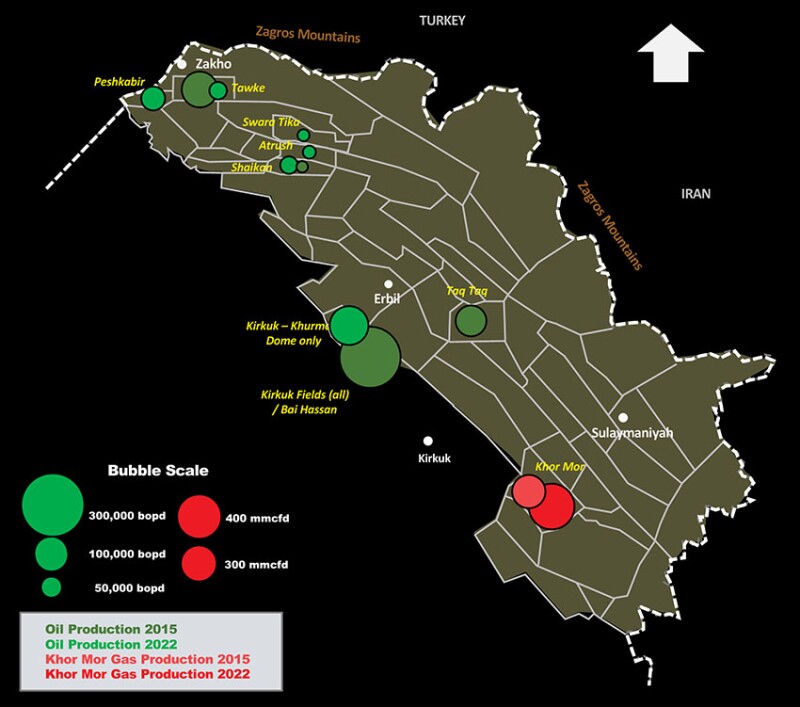

In the 2014–2023 period, fields continued to be appraised while development and production were ongoing, something that is commonly observed in the KRI. Some new field development plans were prepared, including for fields such as Sarsang, Khor Mor, Chemchemal, Kurdamir, Baeshiqa, and Sarta, while some existing fields such as Shaikan had updates to their original plans submitted. Fig. 1 shows a map of the region, including production from key fields for 2 representative years to give a snapshot of the changes that occurred in this period.

A Closer Look Into the KRI Production Fluctuations in the Past Decade

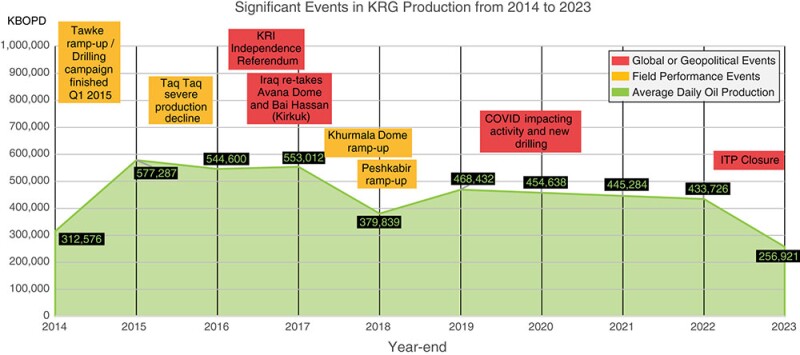

To understand the full picture of the evolution of hydrocarbon production in the KRI over the past decade, the evaluation needs to consider the geopolitical and global events that took place, in addition to the technical aspects related to the different fields. Fig. 2 displays the total production from 2014 to 2023 matched with relevant events.

As a result of the Islamic State group’s presence in Iraq in 2014, the KRG took control of the Kirkuk and Bai Hassan fields in the Kirkuk disputed area that had until then been operated by the Federal Government of Iraq’s North Oil Company. This was the main factor contributing to the increase of production in the region to 577,000 BOPD in 2015, from 312,000 in 2014. Combined production for Kirkuk’s Avana Dome and Bai Hassan fields was estimated to be 230,000 BOPD by 2016.

The second most-relevant contributor to this significant production increase by the end of 2015 was an incremental 44,000 BOPD from the Tawke field, which came as a result of a continued, successful drilling campaign involving high-angle and horizontal wells. This campaign started in 2012 with the drilling of Tawke-20, which penetrated 600 m of reservoir section. Initial results were shared by mid-2013, indicating a record rate for this well of 25,000 BOPD, compared to 10,000 BOPD for the best existing vertical producer. Tawke-20 was followed by nine other horizontals in the field, drilled up until the first months of 2015. The production from Taq Taq and Shaikan was also increased from 2014 to 2015, contributing over 13,000 BOPD each to the uplift in the region at that time.

2015 marked the peak of oil production in the KRI. The average daily rate stood above the 500,000 BOPD mark between 2015 and 2017. The Tawke field sustained a production level above 100,000 BOPD during this 3-year period, making it the best-producing field after the Kirkuk fields up until 2020, even though it was by then in decline.

Pushing production down from 2015 onward was the pronounced decline of the flagship Taq Taq field, which had been one of the largest producers in 2014. An increase in water production coincided with an oil production drop from 116,000 BOPD in 2015 to 18,000 in 2017. Genel Energy, a partner in the joint-venture operating company TTOPCO, attributed this to an original overestimate in the porosity of one of the main reservoirs. Regardless of the causes, this highlights the difficulties of predicting future performance in the structurally complicated fractured carbonate reservoirs present in the KRI.

In early 2017, following the drilling of the Peshkabir-2 well, an oil discovery was announced in the Peshkabir field, which is part of the Tawke production-sharing contract. The field was put into production and quickly ramped up to over 25,000 BOPD average in 2018. On the other hand, later in 2017, after the KRI’s independence referendum, the Federal Government of Iraq retook the control and operation of Kirkuk’s Avana Dome and Bai Hassan fields. This brought the KRI’s production down to 380,000 BOPD average in 2018, from more than 550,000 the previous year. The KRI retained control over Kirkuk’s Khurmala Dome field, which remains the highest-producing field in the region up to present.

In 2019, the KRI’s average oil production rose to 468,000 BOPD, which is 70,000 more than in 2018. The Tawke license contributed 37,000 of that increment, of which 9,600 incremental came from the Tawke Field and 27,400 incremental from the Peshkabir Field, in its third year onstream.

From 2019 to 2022, production for the region experienced a slight year-to year decline, going from 468,000 BOPD in 2019 to 434,000 in 2022. The COVID-19 outbreak in 2020 temporarily impacted the drilling of some new wells and other activities, with a recovery observed in 2021. The Tawke field continued with a controlled decline throughout this period, averaging 47,000 BOPD in 2021. Meanwhile, for the younger Peshkabir field, DNO increased production to 62,000 BOPD in 2021 from 53,000 in 2020.

The Atrush field also belongs to the small group of fields that has surpassed a yearly production of 40,000 BOPD at some point in its lifetime. This landmark was achieved in 2020, when the closing annual average production was slightly over 45,000 BOPD, an increase from 32,000 in 2019. After 2021, the production level slipped below 40,000. One new producer was brought online in February 2023, while a second producer was drilled and put on hold awaiting the resumption of export through the ITP.

Neighboring Atrush to the north, the Sarsang Block containing the Swara Tika field (along with the more recently developed East Swara Tika) represents a case of continuous growth since the start of production in 2014, closing 2022 with an average production of 33,200 BOPD from 7 wells between both fields. Following the commissioning of a new 25,000-BOPD facility in Q3 2022, the operator had plans to take the average production above 50,000 BOPD in 2023 before international exports were interrupted.

In the southern part of the KRI, the operator of the Sarqala field reported production peaks of 35,000 BOPD and 33,000 during 2019 and 2021, respectively. Data covering a longer period and up to present is not readily available.

Following the previously mentioned ITP closure at the end of Q1 2023, IOCs had to stop production immediately, having minimal or no storage capacity. However, over the course of the following months, they negotiated agreements to sell the oil locally, albeit at prices heavily discounted, somewhat mitigated by receiving upfront payments for their production. As of May 2024, production in the region is estimated to have recovered to a level of 300,000 BOPD from an average of 408,000 in Q1 2023 before the ITP closure occurred.

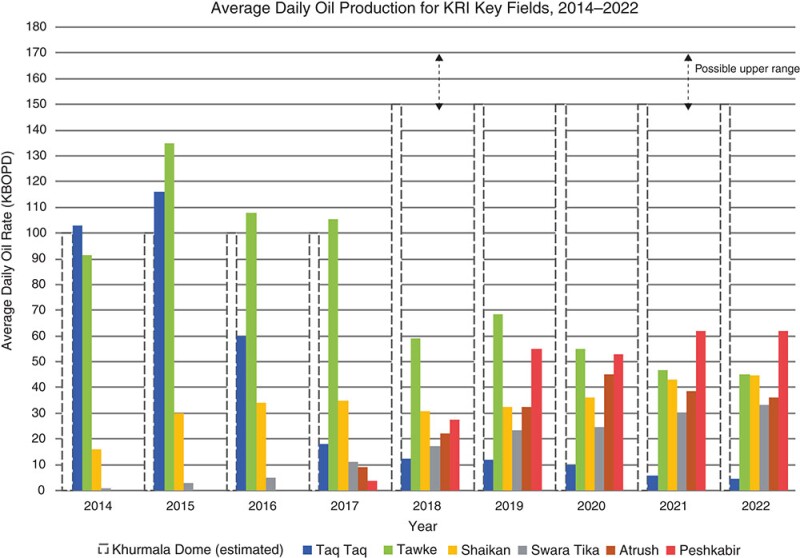

Fig. 3 shows a comparative bar chart for seven key oil-producing fields between 2014 and 2022. It should be noted that: 1) accurate production information and breakdown for the Khurmala Dome field is difficult to obtain and therefore it has been estimated, and 2) the year 2023 is excluded from the plot as it is affected by the ITP closure.

While Khurmala Dome continues to be the largest producing field, the overall picture for the remainder of oil production has changed. The chart shows that until 2017 there were fewer fields with each contributing larger volumes. More recently, there has been a larger number of fields, both mature declining and younger ramping up, each delivering smaller but more sustained volumes over time. One interpretation of this trend is that the larger accumulations of oil have been discovered and produced (to a certain extent) and that any new fields will be smaller. This would fit with the “creaming curve” hypothesis for how basins are explored and developed. An alternative interpretation is that operators are more cautious in how quickly they invest capital, given the technical, operational and commercial challenges of operating in the region. These are not mutually exclusive.

Some Remarks on KRI Gas Production and Utilization

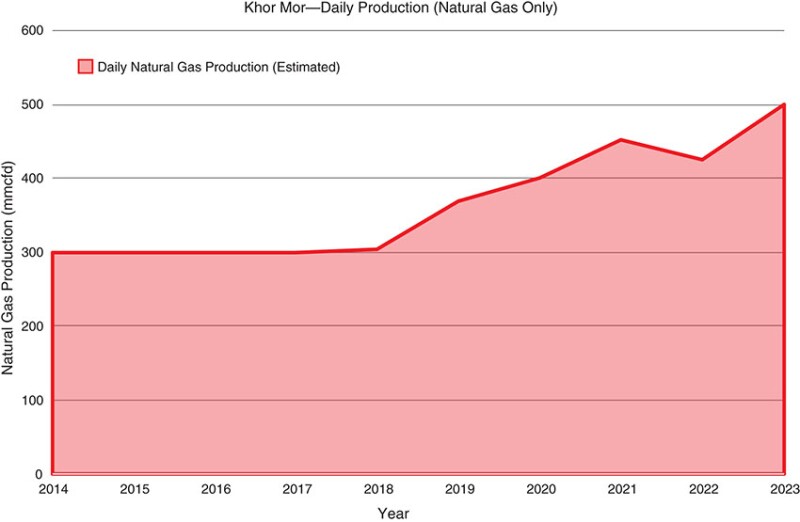

Gas reserves in the KRI are estimated to be in the range of 25 Tcf which would represent 0.35% of the worldwide gas reserves. Nonetheless, gas production and utilization projects in the KRI are still in relatively early, evolving stages. Gas production currently comes from two fields: Khor Mor (nonassociated gas) and Khurmala Dome (associated gas). The Khor Mor gas field, operated by the Pearl Consortium and accounting for 90% of gas provision in the region, started production in August 2008. Fig. 4 shows Khor Mor production performance in the decade from 2014 to 2023. During the initial 5 years of this period, production was nearly constant at 300 MMscf/D. Following arbitration on a contractual dispute between Pearl and the KRG, in 2018 there was an agreement between the parties to increase production. By 2021 production had increased to above 450 MMscf/D. A further expansion of 250 MMscf/D (known as the “KM250 project”) is currently being executed. However in April this year, Khor Mor suffered a significant drone attack, causing four casualties and the suspension of activities for several days. By May 2024 gas production had resumed, with the operator stating that daily production was exceeding 500 MMscf/D of gas, 1,100 metric tons of LPG, and 15,000 B/D of condensate.

Further development of the significant gas resources in the KRI will require an export pipeline. Various schemes have been proposed over the past 10 years, but none have made it into execution. Much of the gas in the KRI contains significant proportions of H2S which needs to be removed before export and therefore increases the cost of upstream and midstream processing facilities. Gas from Khor Mor does not have this property, which is one of the reasons why it was developed first. Nevertheless, development of gas resources with high H2S content is feasible and has been done in other parts of the world, e.g., Kashagan (in construction), Tengiz, and Karachaganak fields in Kazakhstan. The same will be possible in the KRI with suitable commercial agreements for the whole value chain.

Future Perspectives

The experience of the past decade has led most operators to pursue a development and production strategy that can be characterized as “learn as you go” where appraisal is ongoing through a phased development. A consequence of this “appraise while developing/producing” philosophy is that fields can be brought onto production more quickly, but production will increase relatively slowly as future phases need to be justified for development. This strategy is at least partly a consequence of the complicated, highly folded, faulted and fractured geology in the region. This makes the subsurface data difficult to interpret and the reservoirs more challenging to model in conventional ways. Understanding of reservoir structure and performance only comes once there is significant production history.

Negotiations to reopen the ITP and to resolve new contractual terms for IOCs will play a key role in dictating both oil production and activity levels in the years to come. The potential for decarbonization of oil production together with further gas production and sales remains unaltered. Political and regulatory stability is needed for these goals to materialize.

Thank you to the colleagues and friends with whom we discussed some of the topics covered in this article.

Production Data Sources

Ministry of Natural Resources, Kurdistan Regional Government (2024). Publications—Oil.

DNO (2024). Reports and Presentations.

Genel Energy (2024). Press Releases.

Gulf Keystone Petroleum (2024). Operations—Production.

ShaMaran Petroleum Corp. (2024). News.

Dana Gas (2024). KRI Operations.

Pearl Petroleum (2024). Operations & News.

Andy Sewell is Xodus Group’s director of subsurface. He has close to 33 years’ experience working in the oil and gas industry, initially as a geophysicist. Sewell has worked across Africa, the Middle East, and Europe delivering projects including exploration management, field development plans, and due diligence investigations. He holds an MA in physics from Cambridge University.

Mariana Olmeda is a Middle East-based senior geoscientist working for the Xodus Group. She has over 20 years of experience in the oil and gas industry, and since 2013 has worked for diverse blocks and projects in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. She holds a degree in geophysical engineering with a specialization in oilfield development from the University of Buenos Aires.