Declining production has defined the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) for more than 2 decades. But today the top issue is whether the basin is in a race to zero or if there is still a chance of a softer landing.

At its peak in 1999, the UKCS produced 2.9 million B/D, nearly 4% of global supply. By 2024, output was down to 630,000 B/D, equal to just 0.5% of world production.

Natural depletion explains much of the decline, but recent policy moves are now considered a more pressing factor.

At the center of debate is the Energy Profits Levy (EPL), which has progressively raised the tax on UKCS oil and gas profits from 40 to 78%. That’s more than double rates of other mature basins such as the US Gulf of Mexico, where the US government take ranges from 31 to 35%.

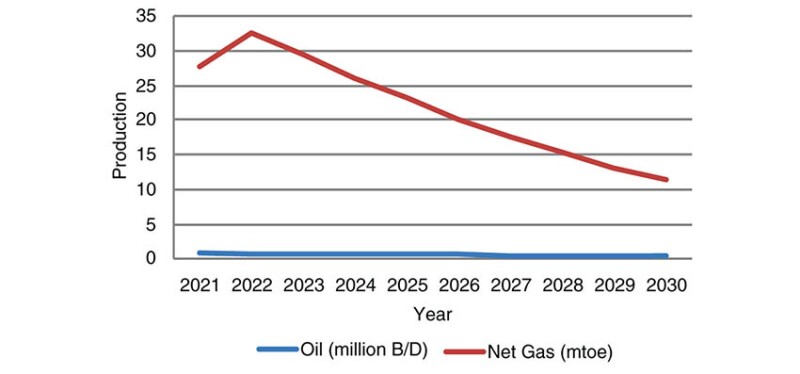

Since a Conservative-led government imposed the profit windfall tax in 2022, production has fallen by more than one third, or 190,000 B/D. The North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA), the UK’s offshore regulator, projects output will decline another third by 2030, leaving the country with about 420,000 B/D of domestic supply.

The now Labour-led government has thrown its full support behind the EPL and will decide in November how to replace it when it expires in 2030. Meanwhile, the industry is urging for its repeal altogether.

Wood Mackenzie noted in September that the UK is already facing a difficult investment environment, with 90% of its recoverable resources produced or under development. The consultancy estimates about 1 billion BOE can be developed under current terms, while another 5 billion BOE would require stronger policy support and removal of the EPL.

A ‘Difficult’ Situation

The EPL, introduced in response to soaring energy prices after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, has drawn sharp criticism from observers who say it is hastening decline.

Few know the UKCS as well as Alexander Kemp, author of the two-volume Official History of North Sea Oil and Gas and professor of petroleum economics at the University of Aberdeen. He chose the word “difficult” to sum up the region’s outlook.

“We have done quite a bit of modeling work on the effect of the windfall profit tax, the EPL, and have consistently found that there are significant disincentives to explore and incur field development expenditures,” Kemp said. “The current situation is one where investment is falling at a very strong rate.”

And while most of the remaining reservoirs are small, that has become a moot point under the Labour-led government, which since taking power last year has stopped issuing new exploration licenses in its push toward net-zero emissions.

Policymakers argue that decline is unavoidable given the basin’s maturity and frame it as an opportunity to cut emissions and expand renewables, particularly offshore wind.

Kemp notes this ignores the growing reliance on imports.

“That is happening to some extent,” he said of an uptick in renewable investments, “but what is not said is that our import bill for oil and gas is very high, and all the projections I can think of show the import bill will grow higher still.”

Still Time To Reverse Course?

By the time the EPL expires in 2030, the UK may go from producing about half of its own oil and gas to importing 80%. The warning came in a September report from industry trade group Offshore Energies UK, which stressed that hydrocarbons still account for 75% of national energy demand.

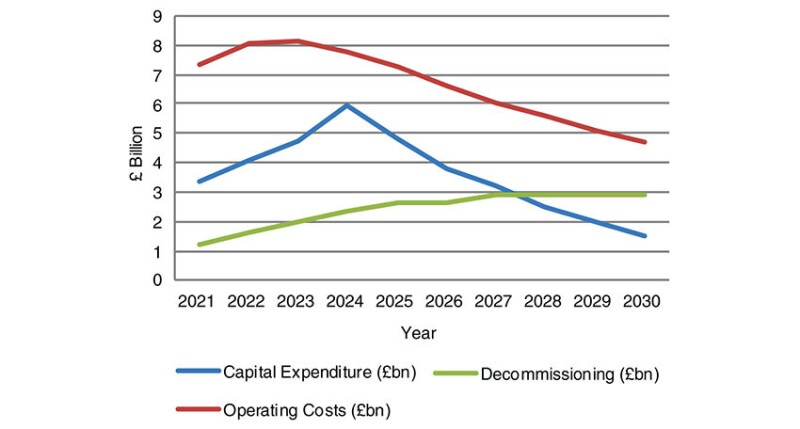

The slowdown is already visible. NSTA data show spending on exploration and appraisal fell from GBP 370 million in 2021 to just GBP 100 million in 2024, a level expected to persist through 2030. Capital expenditures and operating costs, which totaled GBP 5.95 billion and GBP 7.78 billion in 2024, are projected to fall to GBP 1.5 billion and GBP 4.7 billion by 2030.

The one segment showing growth is decommissioning. Spending reached GBP 2.35 billion last year and is expected to climb to GBP 2.9 billion by 2027 and remain near that record level throughout the decade.

The government is not backing away from the EPL, but it did open a public consultation this year on what should eventually replace the surtax. Analysts say this position will lock the basin into minimal investment and activity.

“While the current consultation aims to land upon a new fiscal mechanism when oil and gas prices are ‘unusually high’ after 2030, we have made the point many times that 2030 in the remaining life of the UK North Sea is far too long to wait,” said Gail Anderson, research director at Wood Mackenzie.

She added, “If the EPL doesn’t end next year as industry would like, some companies may decide that the meager cash margins are not worth it and look to invest in much more favorable countries. TotalEnergies and INEOS are among those making noises to that effect.”

In September, INEOS executives announced the London-based company had halted UK investment, planned to shut a domestic refinery, and would redirect billions of pounds in capital spend to the US.

TotalEnergies, meanwhile, warned last year it was weighing further reductions in UK spending after already cutting 25% from its 2023 UKCS budget. The move followed a $1 billion EPL tax charge that the French supermajor paid the year before.

Apache Corp., operator of the Forties field, is preparing to walk away from the UKCS completely by 2029, following the government’s increase of the levy last year to 38% above the standard 40% rate while also extending the EPL by a year to March 2030.

US supermajor Chevron and UK independent Harbour Energy also said last year they are exploring UKCS exits, but there remains a question of who will buy the assets.

EPL Debated at Offshore Europe

Policy looms so large over the UKCS that the EPL became a focal point at SPE Offshore Europe (OE) in Aberdeen last month, where more than 25,000 professionals gathered.

Among the conference’s headline speakers was Conservative opposition leader Kemi Badenoch, who said her party was prepared to reverse course on the EPL it introduced 3 years earlier. She argued the levy is generating less revenue and endangering 200,000 jobs.

“When the [EPL] was introduced, oil prices were near record highs at the same time bills were rocketing,” she said. “That moment has long gone. There is no windfall left, and yet Labour is still taxing.”

UK Energy Minister Michael Shanks told delegates at OE that the Labour government intends to “provide long-term certainty” when it unveils the eventual replacement for the EPL.

He also praised the industry’s legacy but underscored that the UK is already deep into its energy transition. Even so, he argued the future cannot be framed as renewables versus hydrocarbons, noting that oil and gas will remain a central component of the UK’s energy mix for decades to come.

“And so, we will support businesses to manage existing fields for the entirety of their lifespan,” Shanks said.

Extending Lifespans

With new projects off the table, the NSTA sees well intervention as a lever to sustain production. The regulator shared a new paper at OE this year which pointed out that about one-third of UKCS wellbores are either temporarily shut in or permanently plugged.

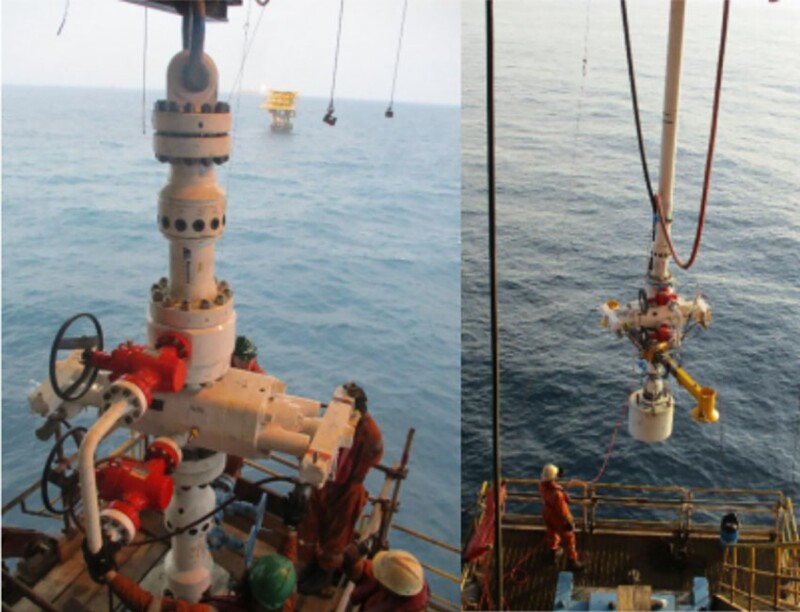

In SPE 226729, the NSTA presented what it called its first major study of well intervention, a “forensic examination” of nearly 440 operations carried out across the UKCS in 2023. The review found that interventions delivered an average of more than 100,000 BOE per job at a cost of about $13.10/BOE.

“The findings clearly demonstrate that reactivating shut-in wells, many of which are technically viable, offers a faster, less carbon-intensive route to domestic production,” said the NSTA authors.

Whether operators will embrace this remains unclear. Intervention activity has fallen by more than a quarter since 2019, when about 600 jobs were completed.

Another paper presented at OE highlighted the same opportunity. SPE 226778, presented by authors from the offshore engineering firm Aquaterra Energy, argued that with the EPL in place and “evolving compliance requirements” weighing on operators, investment is being pulled back. As a result, the authors wrote, “new wells can no longer be relied on to maintain basin production; well intervention activities must form part of the ongoing strategy for the North Sea.”

Still, the paper acknowledged the challenges with relying on well intervention. Aquaterra’s authors said the ongoing drop in intervention activity has several drivers behind it, including technical issues, uncertainty about downhole conditions, equipment obsolescence, and the cost and complexity of deploying light well-intervention vessels.

Their solution is to deploy jackup rigs and lift boats combined with modern subsea systems to provide a more stable and cost-effective option.

The New Model Isn’t So New

Technology aside, the biggest factor that could reshape the UKCS remains fiscal policy. Wood Mackenzie is among those advising the government to consider a profits-based approach that links the state’s share of revenue to oil prices.

“It is rarely an on/off mechanism, however. Usually there is a progressive sliding scale, so the rate increases and decreases in several steps,” Anderson said.

Such frameworks are common in production-sharing contracts, though they bring complications such as cost-recovery mechanisms for exploration work, which Anderson noted “can be contentious.”

Courts Strike Down New Projects

In January, UK courts sent two of the basin’s biggest new projects back to square one on licensing, Shell’s Jackdaw gas development and Equinor’s Rosebank oil project. Judges ruled their approvals illegal for failing to account for Scope 3 emissions.

Jackdaw, approved in 2022, is awaiting new approvals while Shell continues construction of its platform in Norway. If completed, it could supply about 6% of UK gas demand, enough for 1.4 million homes.

Equinor reached final investment decision on Rosebank in 2023, but the project faces similar uncertainty. The field was expected to deliver about 350 million BOE over its life and up to 7% of UK oil output.

Equinor has pledged to electrify the project’s floating production, storage, and offloading unit to cut carbon intensity from 12 kg CO2 per bbl to about 3 kg, which the Norwegian company points out is well below the North Sea average of 20 kg per bbl.

In December 2024, Equinor and Shell announced they were combining their North Sea assets as a cost-efficiency measure. The joint venture, named Adura, includes Rosebank and Jackdaw along with several other assets to create the UKCS’s largest independent operator with around 140,000 BOE/D of production.

Lessons from a Neighbor

One thing that stands out about the UK’s trajectory is how it contrasts with Norway’s. The two countries share the North Sea and a long legacy of oil and gas exploration. But the UKCS is winding down while Norway is mounting something of a comeback.

After peaking at 3.4 million B/D in 2001, Norwegian production hit a decade-high 1.96 million B/D this August after the Johan Castberg project achieved plateau production of 220,000 B/D.

Anderson noted that Norway’s model “has state ownership and control at its heart,” resulting in a more measured approach to resource management with the country’s sovereign wealth fund in mind. “This has meant more controlled release of acreage and fewer participants than the UKCS, so fewer wells drilled,” she said.

By contrast, the UK embraced a free-market approach in the 1980s, leading to a rapid buildout.

Kemp noted that Norway has also benefited from larger fields and a near-total reliance on hydropower, which shrinks domestic demand.

“The headline tax rate [in Norway] is also 78%, but the tax treatment of exploration is much more favorable,” he said, speaking to the cost recovery mechanisms for exploration efforts that the EPL does not account for.

Anderson added the other big distinction between the UK and Norway on this matter is fiscal stability. Norway is simply more predictable, which, when it comes to capital investments, tends to be an attractive attribute.

“As an investor you know you will get 22% of the pre-tax cash flow. So, although the government share is high, you can live with that because it’s predictable and fair. The UK has completely lacked this in the last few years.”

For Further Reading

SPE 226778 From Stranded Assets to Active Production: Making Mature Fields Work Harder by W.L. Cannell and B. Cannell, Aquaterra Energy.

SPE 226729 Accelerating Well Intervention in the UKCS—The North Sea Transition Authority Viewpoint by R. Cygan-Taylor and K. Hogg, North Sea Transition Authority.